Synesthesia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

- "Synopsia" redirects here. For the geometer moth genus, see Synopsia (moth).

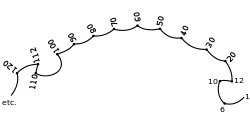

Synesthesia (also spelled synæsthesia or synaesthesia, plural synesthesiae or synaesthesiae)—from the Ancient Greek σύν (syn), "together," and αἴσθησις (aisthēsis), "sensation" — is a neurologically based phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. [1][2][3] People who report such experiences are known as synesthetes. In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme → color synesthesia or color-graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored,[4][5] while in ordinal linguistic personification, numbers, days of the week and months of the year evoke personalities.[6][7] In spatial-sequence, or number form synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, and/or days of the week elicit precise locations in space (for example, 1980 may be "farther away" than 1990), or may have a (three-dimensional) view of a year as a map (clockwise or counterclockwise).[8][9][10] Yet another recently identified type, visual motion → sound synesthesia, involves hearing sounds in response to visual motion and flicker.[11] Over 60 types of synesthesia have been reported by people,[12] but only a fraction has been evaluated by scientific research.[13] Even within one type, synesthetic perceptions vary in intensity [14] and people vary in awareness of their synesthetic perceptions.[15]

While cross-sensory metaphors (e.g., "loud shirt," "bitter wind" or "prickly laugh") are sometimes described as "synesthetic," true neurological synesthesia is involuntary. It is estimated that synesthesia could possibly be as prevalent as 1 in 23 persons across its range of variants.[16] Synesthesia runs strongly in families, but the precise mode of inheritance has yet to be ascertained. Synesthesia is also sometimes reported by individuals under the influence of psychedelic drugs, after a stroke, during a temporal lobe epilepsy seizure, or as a consequence of blindness or deafness. Synesthesia that arises from such non-genetic events is referred to as "adventitious synesthesia" to distinguish it from the more common congenital forms of synesthesia. Adventitious synesthesia involving drugs or stroke (but not blindness or deafness) apparently only involves sensory linkings such as sound → vision or touch → hearing; there are few, if any, reported cases involving culture-based, learned sets such as graphemes, lexemes, days of the week, or months of the year.

Although synesthesia was the topic of intensive scientific investigation in the late 1800s and early 1900s, it was largely abandoned by scientific research in the mid-20th century, and has only recently been rediscovered by modern researchers.[17] Psychological research has demonstrated that synesthetic experiences can have measurable behavioral consequences, while functional neuroimaging studies have identified differences in patterns of brain activation.[5] Many people with synesthesia use their experiences to aid in their creative process, and many non-synesthetes have attempted to create works of art that may capture what it is like to experience synesthesia. Psychologists and neuroscientists study synesthesia not only for its inherent interest, but also for the insights it may give into cognitive and perceptual processes that occur in synesthetes and non-synesthetes alike.

[edit] Definitional criteria

Although sometimes spoken of as a "neurological condition," synesthesia is not listed in either the DSM-IV or the ICD classifications, since it does not, in general, interfere with normal daily functioning. Indeed most synesthetes report that their experiences are neutral, or even pleasant.[18] Rather, like color blindness or perfect pitch, synesthesia is a difference in perceptual experience and the term "neurological" simply reflects the brain basis of this perceptual difference. To date, no research has demonstrated a consistent association between synesthetic experience and other neurological or psychiatric conditions, although this is an active area of research (see below for associated cognitive traits).

It was once assumed that synesthetic experiences were entirely different from synesthete to synesthete, but recent research has shown that there are underlying similarities that can be observed when large numbers of synesthetes are examined together. For example, sound-color synesthetes, as a group, tend to see lighter colors for higher sounds[19] and grapheme-color synesthetes, as a group, share significant preferences for the color of each letter (e.g., A tends to be red; O tends to be white or black; S tends to be yellow etc.,[18][20][21]). Nonetheless, there are a great number of types of synesthesia, and within each type, individuals can report differing triggers for their sensations, and differing intensities of experiences. This variety means that defining synesthesia in an individual is difficult, and indeed, the majority of synesthetes are not aware that their experiences have a name.[18] However, despite the differences between individuals, there are a few common elements that define a true synesthetic experience.

Neurologist Richard Cytowic identifies the following diagnostic criteria of synesthesia:[1][2]

- Synesthetic images are spatially extended, meaning they often have a definite "location."

- Synesthesia is involuntary and automatic.

- Synesthetic percepts are consistent and generic (i.e. simple rather than imagistic).

- Synesthesia is highly memorable.

- Synesthesia is laden with affect.

Although Cytowic suggested that synesthetic experiences are necessarily spatially extended, more recent research has shown many cases where this is not true. For example, some synesthetes "know" the color of their letters or the taste of their words, but do not experience them as a color in space or a taste on the tongue (see below).

[edit] Experiences

Synesthetes often report that they were unaware their experiences were unusual until they realized other people did not have them, while others report feeling as if they had been keeping a secret their entire lives, as has been documented in interviews with synesthetes on how they discovered synesthesia in their childhood.[13] The automatic and ineffable nature of a synesthetic experience means that the pairing may not seem out of the ordinary. This involuntary and consistent nature helps define synesthesia as a real experience. Most synesthetes report that their experiences are pleasant or neutral, although, in rare cases, synesthetes report that their experiences can lead to a degree of sensory overload.[18]

Though often stereotyped in the popular media as a medical condition or neurological aberration, synesthetes themselves do not experience their synesthetic perceptions as a handicap. To the contrary, most report it as a gift—an additional "hidden" sense—something they would not want to miss. Most synesthetes have become aware of their "hidden" and different way of perceiving in their childhood. Some have learned how to apply this gift in daily life and work. Synesthetes have used their gift in memorizing names and telephone numbers, mental arithmetic, but also in more complex creative activities like producing visual art, music, and theater.[13]

Despite the commonalities which permit definition of the broad phenomenon of synesthesia, individual experiences vary in numerous ways. This variability was first noticed early on in synesthesia research[22] but has only recently come to be re-appreciated by modern researchers. Some grapheme → color synesthetes report that the colors seem to be "projected" out into the world, while most report that the colors are experienced in their "mind's eye."[23] Additionally, some grapheme → color synesthetes report that they experience their colors strongly, and show perceptual enhancement on the perceptual tasks described below, while others (perhaps the majority) do not,[14] perhaps due to differences in the stage at which colors are evoked. Some synesthetes report that vowels are more strongly colored, while for others consonants are more strongly colored.[18] In summary, self reports, autobiographical notes by synesthetes and interviews show a large variety in types of synesthesia, intensity of the synesthetic perceptions, awareness of the difference in perceiving the physical world from other people, the way they creatively use their synesthesia in work and daily life.[13][24] The descriptions below give some examples of synesthetes' experiences, which have been experimentally tested, but do not exhaust their rich variety.

[edit] Various forms

Synesthesia can occur between nearly any two senses or perceptual modes. Given the large number of forms of synesthesia, researchers have adopted a convention of indicating the type of synesthesia by using the following notation x → y, where x is the "inducer" or trigger experience, and y is the "concurrent" or additional experience. For example, perceiving letters and numbers (collectively called graphemes) as colored would be indicated as grapheme → color synesthesia. Similarly, when synesthetes see colors and movement as a result of hearing musical tones, it would be indicated as tone → (color, movement) synesthesia.

While nearly every logically possible combination of experiences can occur, several types are more common than others.

[edit] Grapheme → color synesthesia

In one of the most common forms of synesthesia, grapheme → color synesthesia, individual letters of the alphabet and numbers (collectively referred to as graphemes), are "shaded" or "tinged" with a color. While synesthetes do not, in general, report the same colors for all letters and numbers, studies of large numbers of synesthetes find that there are some commonalities across letters (e.g., A is likely to be red).[18][20]

A grapheme → color synesthete reports, "I often associate letters and numbers with colors. Every digit and every letter has a color associated with it in my head. Sometimes, when letters are written boldly on a piece of paper, they will briefly appear to be that color if I'm not focusing on it. Some examples: 'S' is red, 'H' is orange, 'C' is yellow, 'J' is yellow-green, 'G' is green, 'E' is blue, 'X' is purple, 'I' is pale yellow, '2' is tan, '1' is white. If I write SHCJGEX it registers as a rainbow when I read over it, as does ABCPDEF."[25]

"'Until one day,' I said to my father, 'I realized that to make an R all I had to do was first write a P and draw a line down from its loop. And I was so surprised that I could turn a yellow letter into an orange letter just by adding a line'"

– Patricia Lynne Duffy, recalling an earlier experience, from her book Blue Cats and Chartreuse Kittens

Another reports a similar experience. "When people ask me about the sensation, they might ask, 'so when you look at a page of text, it's a rainbow of color?' It isn't exactly like that for me. When I read words, about five words around the exact one I'm reading are in color. It's also the only way I can spell. I remember in elementary school remembering how to spell the word 'priority' because the color scheme, in general, was darker than many other words. I would know that an 'e' was out of place in that word because e's were yellow and didn't fit."[25]

Another reports a slightly different experience. "When I actually look at words on a page, the letters themselves are not colored, but instead in my mind they all have a color that goes along with them, and it has always been this way. I remember back in kindergarten thinking that each homeroom had a different color associated with it. I would sometimes say things referring to that class and calling it by its color. It is also like this with days of the week, months, and so on. I thought this was caused by me over-thinking things. But I finally have come to realize that Synesthesia is real."[25]

[edit] Sound → color synesthesia

In sound → color synesthesia, individuals experience colors in response to tones or other aspects of sounds. Simon Baron-Cohen and his colleagues break this type of synesthesia into two categories, which they call "narrow band" and "broad band" sound → color synesthesia. In narrow band sound → color synesthesia (often called music → color synesthesia), musical stimuli (e.g., timbre or key) will elicit specific color experiences, such that a particular note will always elicit red, or harps will always elicit the experience of seeing a golden color. In broadband sound → color synesthesia, on the other hand, a variety of environmental sounds, like an alarm clock or a door closing, may also elicit visual experiences.

Color changes in response to different aspects of sound stimuli may involve more than just the hue of the color. Any dimension of color experience (see HSL color space) can vary. Brightness (the amount of white in a color; as brightness is removed from red, for example, it fades into a brown and finally to black), saturation (the intensity of the color; fire engine red and medium blue are highly saturated, while grays, white, and black are all unsaturated), and hue may all be affected to varying degrees.[26] Additionally, music → color synesthetes, unlike grapheme → color synesthetes, often report that the colors move, or stream into and out of their field of view.

Like grapheme → color synesthesia, there is rarely agreement among music → color synesthetes that a given tone will be a certain color. However, when larger samples are studied, consistent trends can be found, such that higher pitched notes are experienced as being more brightly colored.[19] The presence of similar patterns of pitch-brightness matching in non-synesthetic subjects suggests that this form of synesthesia shares mechanisms with non-synesthetes.[19]

[edit] Number form synesthesia

A number form is a mental map of numbers, which automatically and involuntarily appears whenever someone who experiences number-forms thinks of numbers. Number forms were first documented and named by Francis Galton in "The Visions of Sane Persons".[27] Later research has identified them as a type of synesthesia.[9][10] In particular, it has been suggested that number-forms are a result of "cross-activation" between regions of the parietal lobe that are involved in numerical cognition and spatial cognition.[28][29] In addition to its interest as a form of synesthesia, researchers in numerical cognition have begun to explore this form of synesthesia for the insights that it may provide into the neural mechanisms of numerical-spatial associations present unconsciously in everyone.

[edit] Personification

Ordinal-linguistic personification (OLP, or personification for short) is a form of synesthesia in which ordered sequences, such as ordinal numbers, days, months and letters are associated with personalities.[6][30] Although this form of synesthesia was documented as early as the 1890s[22][31] modern research has, until recently, paid little attention to this form.

"T’s are generally crabbed, ungenerous creatures. U is a soulless sort of thing. 4 is honest, but… 3 I cannot trust… 9 is dark, a gentleman, tall and graceful, but politic under his suavity"

– Synesthetic subject report[31]

"I [is] a bit of a worrier at times, although easy-going; J [is] male; appearing jocular, but with strength of character; K [is] female; quiet, responsible…"

– Synesthetic subject MT report[1]

For some people in addition to numbers and other ordinal sequences, objects are sometimes imbued with a sense of personality, sometimes referred to as a type of animism. This type of synesthesia is harder to distinguish from non-synesthetic associations. However, recent research has begun to show that this form of synesthesia co-varies with other forms of synesthesia, and is consistent and automatic, as required to be counted as a form of synesthesia.[6]

[edit] Lexical → gustatory synesthesia

In a rare form of synesthesia, lexical → gustatory synesthesia, individual words and phonemes of spoken language evoke the sensations of taste in the mouth.

Whenever I hear, read, or articulate (inner speech) words or word sounds, I experience an immediate and involuntary taste sensation on my tongue. These very specific taste associations never change and have remained the same for as long as I can remember.

Jamie Ward and Julia Simner have extensively studied this form of synesthesia, and have found that the synesthetic associations are constrained by early food experiences.[32][33] For example, James Wannerton has no synesthetic experiences of coffee or curry, even though he consumes them regularly as an adult. Conversely, he tastes certain breakfast cereals and candies that are no longer sold.

Additionally, these early food experiences are often paired with tastes based on the phonemes in the name of the word (e.g., /I/, /n/ and /s/ trigger James Wannerton’s taste of mince) although others have less obvious roots (e.g., /f/ triggers sherbet). To show that phonemes, rather than graphemes are the critical triggers of tastes, Ward and Simner showed that, for James Wannerton, the taste of egg is associated to the phoneme /k/, whether spelled with a "c" (e.g., accept), "k" (e.g., York), "ck" (e.g., chuck) or "x" (e.g., fax). Another source of tastes comes from semantic influences, so that food names tend to taste of the food they match, and the word "blue" tastes "inky."

[edit] Research history

The interest in colored hearing, i.e. the co-perception of colour in hearing sounds or music, dates back to Greek antiquity, when philosophers were investigating whether the colour (chroia, what we now call timbre) of music was a physical quality that could be quantified. [34] The seventeenth-century physicist Isaac Newton tried to solve the problem by assuming that musical tones and colour tones have frequencies in common.[35] The age-old quest for colour-pitch correspondences in order to evoke perceptions of coloured music finally resulted in the construction of color organs and performances of colored music in concert halls at the end of the nineteenth century.[36] [37]

The first medical description of colored hearing is found in a thesis by the German physician Sachs in 1812. [38] The father of psychophysics, Gustav Fechner reported on a first empirical survey of colored letter photisms among 73 synesthetes in 1871, [39] [40] followed in the 1880s by Francis Galton.[8][41][42] Following these initial observations, research into synesthesia proceeded briskly, with researchers from England, Germany, France and the United States all investigating the phenomenon. However, due to the difficulties in assessing and measuring subjective internal experiences, and the rise of behaviorism in psychology, which banished any mention of internal experiences, the study of synesthesia gradually waned during the 1930s.

In the 1980s, as the cognitive revolution had begun to make discussion of internal states and even the study of consciousness respectable again, scientists began to once again examine this phenomenon. Led in the United States by Larry Marks and Richard Cytowic, and in England by Simon Baron-Cohen and Jeffrey Gray, research into synesthesia began by exploring the reality, consistency and frequency of synesthetic experiences. In the late 1990s, researchers began to focus on grapheme → color synesthesia, one of the most common[18][21] and easily studied forms of synesthesia. In 2006, the journal "Cortex" published a special issue on synesthesia, composed of 26 articles. Synesthesia has been the topic of numerous scientific books, as well as novels and short films that include characters who experience some form of synesthesia.

Since the 1990s, with the rise of the internet, synesthetes started to contact each other, and create many web pages relating to the condition (see External links below). These early internet and e-mail contacts have now grown into several international organizations for synesthetes, including the American Synesthesia Association, the UK Synaesthesia Association, the Belgian Synaesthesia Association, the German Synesthesia Association and the Netherlands Synesthesia Web Community.

[edit] Prevalence and genetic basis

Estimates of the prevalence of synesthesia have varied widely (from 1 in 20 to 1 in 20,000). However, these studies all suffered from the methodological shortcoming of relying on self-selected samples. That is, the only people included in the studies were those who reported their experiences to the experimenter. Simner et al. conducted the first random population study, arriving at a prevalence of 1 in 23. Recent data suggests that grapheme → color, and days of the week → color variants are most common.[16][18]

Almost every study that has investigated the topic has suggested that synesthesia clusters within families, consistent with a genetic origin for the condition. The earliest references to the familial component of synesthesia date to the 1880s, when Francis Galton first described the condition in Nature. Since then, other studies have supported this conclusion. However, early studies[43][44] which claimed a much higher prevalence in women than in men (up to 6:1) most likely suffered from a sampling bias due to the fact that women are more likely to self-disclose than men. More recent studies, using random samples find a sex ratio of 1.1:1.[16]

Until early 2009, the observed patterns of inheritance were thought to be consistent with an X-linked mode of inheritance because there had been no verified reports of father-to-son transmission, and other forms of transmission (father-to-daughter, mother-to-son and mother-to-daughter) had been reported much more commonly.[1][44][45] However, the first genome-wide association study (GWAS) of synesthesia failed to find any evidence of X-linkage,[46] and additionally reported two verified cases of father-to-son transmission.[46] The GWAS suggests that synesthesia may depend on interactions between several genes, including genetic loci associated with synesthesia on the long arm of chromosome 2 (2q24), the long arm of chromosome 5 (5q33), the short arm of chromosome 6 (6p12) and the short arm of chromosome 12 (12p12). There was no evidence of an association between synesthesia and the X chromosome.[46]

Additionally, pairs of identical twins have been identified where only one member of the pair experiences synesthesia[47][48] and it has been noted that synesthesia can skip generations within a family,[49] consistent with models of incomplete penetrance. Ward and Simner also note that it is quite common for synesthetes within a family to experience different types of synesthesia, suggesting that the gene or genes involved in synesthesia do not lead to specific types of synesthesia.[45] Rather developmental factors such as gene expression and environment must also play a role in determining which types of synesthesia an individual synesthete will experience.

[edit] Objective verification

Proof that someone is a synesthete is easy to come by, and hard to "fake." The simplest test involves test-retest reliability over long periods of time. Synesthetes consistently score higher on such tests than non-synesthetes (either with color names, color chips or even a color picker providing up to 16.7 million color choices). Synesthetes may score as high as 90% consistent over test-retest intervals of up to one year, while non-synesthetes will score 30-40% consistent over test-retest intervals of only one month, even if warned that they will be retested (e.g., [44]).

More specialized tests include using modified versions of the Stroop effect. In the standard Stroop paradigm, it is harder to name the ink color of the word "red" when it is printed in blue ink than if it is presented in red ink. This demonstrates that reading is automatic. Similarly, if a grapheme → color synesthete is presented with the digit 4 that he or she experiences as red in blue ink, he or she is slower to identify the ink color. This is not because the synesthete cannot see the blue ink, but rather because the same sort of "response conflict" that is responsible for the standard Stroop effect is also occurring between the color of the ink and the automatically induced color of the grapheme. This response conflict is strongest if the color of the ink is the opponent color to the synesthetically associated color (e.g., red vs. green), indicating that the perception of synesthetic colors relies on the same mechanisms as the perception of real colors.[50] Similar variants of the Stroop effect can be devised where, for example, a music → color synesthete is asked to name a red color patch while listening to a tone that produces a blue sensation,[51] or where a musical key → taste synesthete is asked to identify a bitter taste while hearing a musical interval that induces a sweet taste.[52]

Finally, studies of grapheme → color synesthesia have demonstrated that synesthetic colors can improve performance on certain visual tasks, at least for some synesthetes. Inspired by tests for color blindness, Ramachandran and Hubbard presented synesthetes and non-synesthetes with displays composed of a number of 5s, with some 2s embedded among the 5s.[28] These 2s could make up one of four shapes; square, diamond, rectangle or triangle. For a synesthete who sees 2s as red and 5s as green, their synesthetic colors help them to find the "embedded figure". Subsequent studies have explored these effects more carefully, and have found that 1) there is substantial variability among synesthetes[23][14] and 2) while synesthesia is evoked early in perceptual processing, it does not occur prior to attention (e.g.,[53][54]).

[edit] Possible neural basis

Theories of the neural basis of synesthesia start from the observation that there are dedicated regions of the brain that are specialized for certain functions. Based on this notion of specialized regions, some researchers have suggested that increased cross-talk between different regions specialized for different functions may account for different types of synesthesia. For example, since regions involved in the identification of letters and numbers lie adjacent to a region involved in color processing (V4), the additional experience of seeing colors when looking at graphemes might be due to "cross-activation" of V4.[28] This cross-activation may arise due to a failure of the normal developmental process of pruning.

Alternatively, synesthesia may arise through "disinhibited feedback" or a reduction in the amount of inhibition along feedback pathways.[55] Normally, the balance of excitation and inhibition are maintained. However, if normal feedback were not adequately inhibited, then signals coming from later multi-sensory stages of processing might influence earlier stages of processing, such that tones would activate visual cortical areas in synesthetes more than in non-synesthetes. In this case, it might explain why some users of psychedelic drugs such as LSD or mescaline report synesthetic experiences while under the influence of the drug.

Functional neuroimaging studies using positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) have demonstrated significant differences between the brains of synesthetes and non-synesthetes. Recent studies using fMRI have demonstrated that V4 is more active in both word → color and grapheme → color synesthetes.[14][56][57] Using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), a technique which allows the visualization of white matter fiber pathways in the intact human brain, Rouw and Scholte have demonstrated increased connectivity in regions of the fusiform gyrus, intraparietal sulcus and frontal cortex.[58] In addition, they showed that the degree of white matter connectivity in the fusiform gyrus correlates with the intensity of the synesthetic experience, suggesting that these anatomical differences are the origin of the synesthetic experience.

[edit] Associated cognitive traits

Very little is known about the overall cognitive traits associated with synesthesia (or, indeed if there are any cognitive traits that are consistently associated with synesthesia). Some studies have suggested that synesthetes are unusually sensitive to external stimuli.[1] Other possible associated cognitive traits include left-right confusion, difficulties with mathematics, and difficulties with writing.[1]

However, synesthetes may be more likely to participate in creative activities,[21] and some studies have suggested a correlation between synesthesia and creativity.[59][60] Other research has suggested that synesthesia may contribute to superior memory abilities.[61][62] However, it is unclear whether this is a general feature of synesthesia or whether it is true of only a small minority. Interviews with synesthetes show that some use their synesthetic abilities for creative purposes or as a general orientation in life, while other who have been tested positively do not use it. Individual development of perceptual, cognitive skills and the social environment in which synesthetes are raised and work probably determine the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic abilities.[24][15] These are major topics of current and future research.

[edit] Links with other areas of study

Researchers study synesthesia not only because it is inherently interesting, but also because they hope that studying synesthesia will offer new insights into other questions, such as how the brain combines information from different sensory modalities, referred to as crossmodal perception and multisensory integration.

One example of this is the bouba/kiki effect. In a psychological experiment first designed by Wolfgang Köhler, people are asked to choose which of two shapes (pictured right) is named bouba and which is named kiki. 95% to 98% of people choose kiki for the angular shape and bouba for the rounded shape. With individuals on the island of Tenerife, Köhler showed a similar preference between shapes called "takete" and "maluma". Recent work by Daphne Maurer and colleagues has shown that even children as young as 2.5 years old (too young to read) show this effect.[63]

Ramachandran and Hubbard suggest that the kiki/bouba effect has implications for the evolution of language, because it suggests that the naming of objects is not completely arbitrary.[28] The rounded shape may most commonly be named bouba because the mouth makes a more rounded shape to produce that sound while a more taut, angular mouth shape is needed to make the sound kiki. The sounds of a K are harder and more forceful than those of a B, as well. The presence of these "synesthesia-like mappings" suggest that this effect might be the neurological basis for sound symbolism, in which sounds are non-arbitrarily mapped to objects and events in the world.

Similarly, synesthesia researchers hope that, because of their unusual conscious experiences, the study of synesthesia will provide a window into better understanding consciousness and in particular on the neural correlates of consciousness, or what the brain mechanisms that allow us to be conscious might be. In particular, some researchers have argued that synesthesia is relevant to the philosophical problem of qualia,[28][64][3] since synesthetes experience additional qualia evoked through non-typical routes.

[edit] Artistic investigations

The phrase synesthesia in art has historically referred to a wide variety of artistic experiments that have explored the co-operation of the senses (e.g. seeing and hearing) in the genres of visual music, music visualization, audiovisual art, abstract film, and intermedia.[13][65][66][67][68][17]

The age-old artistic views on synesthesia have some overlap with the current neuroscientific view on neurological synesthesia, but also some major differences, e.g. in the contexts of investigations, types of synesthesia selected, and definitions. While in a neuroscientific studies synesthesia is defined as the elicitation of perceptual experiences in the absence of the normal sensory stimulation, in the arts the concept of synaesthesia in the arts is more often defined as the simultaneous perception of two or more stimuli as one gestalt experience.[69] The usage of the term synesthesia in art should, therefore, be differentiated from neurological synesthesia in scientific research. Synesthesia is by no means unique to artists or musicians. Only in the last decades scientific methods have become available to assess synesthesia in persons. For synesthesia in artists before that time one has to interpret (auto)biographical information.

Synesthetic art may refer to either art created by synesthetes or art created to convey the synesthetic experience. It is an attempt to understand the relation between the experiences of congenital synesthetes, the experiences of non-synesthetes, and an appreciation of such art by both synesthetes and non-synesthetes. These distinctions are not mutually exclusive, as, for example, art by a synesthete might also evoke synesthesia-like experiences in the viewer. However, it should not be assumed that all "synesthetic" art accurately reflects the synesthetic experience. This latter category is also sometimes referred to as artificial synesthesia.

Historically, synesthetic art consisted of a number of contrivances, such as color organs, musical painting and more recently, visual music, all of which have been intended to evoke cross-sensory fusions in the audience, although the inventors of such artifices were not necessarily synesthetes themselves, and may not even have been aware of synesthesia as such. Numerous modern synesthete artists, including Carol Steen,[70] Marcia Smilack,[71] and others have described in detail the manner in which they use their synesthesia in the creation of their artworks, demonstrating the complex interplay between their personal experiences and their artistic creations.

Synesthesia has been a source of inspiration for artists (e.g. Van Gogh, Kandinsky, Mondrian), composers (e.g. Scriabin, Messiaen, Ligeti), poets and novelists (e.g. Baudelaire, Nabokov) and contemporary digital artists. Kandinsky and Mondrian experimented with image-music correspondences in their paintings. Scriabin composed symphonic poems of sound and color. Messiaen captured the colors of landscapes in music. Baudelaire used synesthesia as a paradigm for symbolist literature. New movements in art (like literary symbolism, non-figurative art and visual music) have profited from artists experimentations with synesthetic perceptions. Synesthetic art forms have contributed to the awareness of synesthetic and multisensensory ways of perceiving in the general public.[13]

[edit] Literary depictions

In addition to its role in art, synesthesia has often been used as a plot device or as a way of developing a particular character's internal states. In order to better understand the influence of synesthesia in popular culture, and how the condition is viewed by non-synesthetes, it is informative to examine books in which one of the main characters is portrayed as experiencing synesthesia. In addition to these fictional portrayals, the way in which synesthesia is presented in non-fiction books to non-specialist audiences is instructive. Author and synesthete, Patricia Lynne Duffy has described four ways in which synesthete characters have been used in modern fiction.

- Synesthesia as Romantic ideal: in which the synesthetic experience illustrates the Romantic ideal of transcending our experience of the world. Books in this category include The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov.

- Synesthesia as pathology: in which synesthesia is portrayed as pathological. Books in this category include The Whole World Over by Julia Glass.

- Synesthesia as Romantic pathology: in which synesthesia is portrayed as pathological, but also as providing an avenue into the Romantic ideal of transcending normal experience. Duffy selects Holly Payne’s novel, The Sound of Blue as an example of this category.

- Synesthesia as health and balance for some individuals: in which synesthesia is portrayed as indicating psychological health and well being. In particular, Duffy selects two novels, Painting Ruby Tuesday by Jane Yardley and A Mango-Shaped Space by Wendy Mass to illustrate this usage of synesthesia as a plot or character device.

Note that not all of the depictions of synesthesia in the fictional works are accurate. Some are highly inaccurate and reflect more about the author's interpretation of synesthesia than about the phenomenon itself.

In Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the creature describes himself as being in a synesthetic state early in his existence even though the phenomenon was not well-documented when the book was written.[72]

[edit] People with synesthesia

There is a great deal of debate about whether or not synesthesia can be identified through historical sources. A small number of famous people have been labeled as synesthetes on the basis of at least two historical sources. This includes individuals of many different talents, such as artists, novelists, composers, musicians, and scientists. For more details, and supporting evidence, see the main list of people with synesthesia.

Artists with synesthesia include the painter David Hockney, who perceives music synesthetically as colors, and who used these synesthetic colors when painting stage sets, but not in creating his other artworks.[73] Also, Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky had the same type of synesthesia (sound and color). Perhaps the most famous synesthete author was Vladimir Nabokov, who had grapheme → color synesthesia, one of the most common types, which he described at length in his autobiography, Speak Memory, and which he sometimes portrays in giving his characters synesthesia.[74] Composers include Duke Ellington (timbre → color),[75] Franz Liszt (music → color),[76] Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov,[77] and Olivier Messiaen, who had a complex form of synesthesia in which chord structures produced synesthetic colors.[78] Notable synesthete scientists include Richard Feynman. Feynman describes in his autobiography, What Do You Care What Other People Think?, that he had the grapheme → color type.[79] The European record-holder for number of digits of pi recited, Daniel Tammet, has synesthesia, and claims to use his ability to "see" and experience numbers as spatial objects, textures and tones to perform advanced mathematical calculations in his head.[80][81] Other notable synesthetes include musicians John Mayer and Patrick Stump; actress Stephanie Carswell; and electronic musician Aphex Twin, who claims to be inspired by lucid dreams as well as synesthesia (music → color). The classical pianist Hélène Grimaud has the condition as well. Although this has not been verified, Pharrell Williams of the hip-hop production group The Neptunes and band N.E.R.D. claims to experience synesthesia,[82] and used this concept as the basis of the N.E.R.D. album Seeing Sounds.

Some of the most frequently mentioned artists in connection with synesthesia probably were not synesthetes. Analyzing compositions such as Prometheus: The Poem of Fire and Mysterium, some researchers argue that the Russian composer Alexander Scriabin was most likely not a synesthete.[83] The synesthetic motifs found in Scriabin's compositions – most noticeably in Prometheus, composed in 1911 – are developed from ideas from Isaac Newton, and follow a circle of fifths.[83] Others have argued that Scriabin, besides his personal synesthetic perceptions, had developed a universal system that associated colors to musical keys, which was based on the literature and meant for public performances.[84] As an artist, he was particularly interested in the psychological effects on the audience when they experienced sound and color simultaneously. His theory was that when the correct color was perceived with the correct sound, ‘a powerful psychological resonator for the listener’ would be created. On the score of Prometheus Scriabin wrote next to the instruments separate parts for the color organ.[13]

The French Romantic poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire wrote poems which focused on synesthetic experience, but were evidently not synesthetes themselves. Baudelaire's Correspondances (1857) (full text available here) introduced the Romantic notion that the senses can and should intermingle. Baudelaire participated in an experiment with hashish by the French psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau and became interested in how the senses correspond in perception. [13] Rimbaud, following Baudelaire, wrote Voyelles (1871) (full text available here) which was perhaps more important than Correspondances in popularizing synesthesia, although he later admitted "J'inventais la couleur des voyelles!" [I invented the colors of the vowels!].

Sean A. Day, a synesthete, and the President of the American Synesthesia Association, maintains a list of people with synesthesia, "pseudosynesthetes," and individuals who are most likely not synesthetic, but who used synesthesia in their art or music.

[edit] Further reading

- Baron-Cohen, S. and Harrison, J. (Eds., 1997). Synaesthesia: Classic and Contemporary Readings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-19764-8.

- Campen, Cretien van. (2007) The Hidden Sense. Synesthesia in Art and Science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press/Leonardo Books. ISBN 0-262-22081-4

- Cytowic, R. (2003). The Man Who Tasted Shapes. New York: Tarcher/Putman. ISBN 0-262-53255-7.

- Dann, K. (1998). Bright Colors Falsely Seen. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-300-06619-8.

- Duffy, P. L. (2001). Blue Cats and Chartreuse Kittens: How Synesthetes Color their Worlds. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-7167-4088-5.

- Harrison, J. (2001). Synaesthesia: The Strangest Thing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-263245-0.

- Robertson, L. and Sagiv, N. (Eds., 2005). Synesthesia: Perspectives from Cognitive Neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516623-X.

- Tammet, D. (2006) Born on a Blue Day: A Memoir of Aspergers and an Extraordinary Mind. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 978-0-34-089974-8.

- Mass, W. (2003) A Mango-Shaped Space. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-52388-7

- Jamie Ward (2008) The Frog who croaked Blue: Synesthesia and the Mixing of the Senses. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-43014-2.

[edit] See also

- Audiovisual art

- Cognitive neuroscience

- Ideophone

- Perception

- Kinesthesia

- Parosmia

- Theory of multiple intelligences (Learning using multiple senses)

- Daniel Tammet

- Visual music

- Visual thinking

- The Yellow Sound

[edit] References

- ^ a b c d e f Cytowic, Richard E. (2002). Synesthesia: A Union of the Senses. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03296-1. OCLC 49395033.[page number needed]

- ^ a b Cytowic, Richard E. (2003). The Man Who Tasted Shapes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53255-7. OCLC 53186027.[page number needed]

- ^ a b Harrison, John E.; Simon Baron-Cohen (1996). Synaesthesia: classic and contemporary readings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19764-8. OCLC 59664610.

- ^ Rich AN, Mattingley JB (January 2002). "Anomalous perception in synaesthesia: a cognitive neuroscience perspective". Nature Reviews Neuroscience 3 (1): 43–52. doi:. PMID 11823804.

- ^ a b Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (November 2005). "Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia". Neuron 48 (3): 509–20. doi:. PMID 16269367. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896-6273(05)00835-4.

- ^ a b c Simner J, Holenstein E (April 2007). "Ordinal linguistic personification as a variant of synesthesia". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 19 (4): 694–703. doi:. PMID 17381259. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.4.694?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ^ Smilek D, Malcolmson KA, Carriere JS, Eller M, Kwan D, Reynolds M (June 2007). "When "3" is a jerk and "E" is a king: personifying inanimate objects in synesthesia". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 19 (6): 981–92. doi:. PMID 17536968. http://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/jocn.2007.19.6.981?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved on 2008-12-27.

- ^ a b c Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature 22: 494–5. doi:.

- ^ a b Seron X, Pesenti M, Noël MP, Deloche G, Cornet JA (August 1992). "Images of numbers, or "When 98 is upper left and 6 sky blue"". Cognition 44 (1-2): 159–96. doi:. PMID 1511585.

- ^ a b Sagiv N, Simner J, Collins J, Butterworth B, Ward J (August 2006). "What is the relationship between synaesthesia and visuo-spatial number forms?". Cognition 101 (1): 114–28. doi:. PMID 16288733. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010-0277(05)00155-1.

- ^ Saenz M, Koch C (August 2008). "The sound of change: visually-induced auditory synesthesia". Current Biology 18 (15): R650–R651. doi:. PMID 18682202. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960-9822(08)00734-3. Retrieved on 2008-12-28.

- ^ Day, Sean, Types of synesthesia. (2009) Types of synesthesia. Online: http://home.comcast.net/~sean.day/html/types.htm, accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h van Campen, Cretien (2007). The Hidden Sense: Synesthesia in Art and Science. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-22081-4. OCLC 80179991.[page number needed]

- ^ a b c d Hubbard EM, Arman AC, Ramachandran VS, Boynton GM (March 2005). "Individual differences among grapheme-color synesthetes: brain-behavior correlations". Neuron 45 (6): 975–85. doi:. PMID 15797557. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896-6273(05)00124-8.

- ^ a b Campen, Cretien van (2009) "The Hidden Sense: On Becoming Aware of Synesthesia" TECCOGS, vol. 1, pp. 1-13.[1]

- ^ a b c Simner J, Mulvenna C, Sagiv N, et al (2006). "Synaesthesia: the prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences". Perception 35 (8): 1024–33. doi:. PMID 17076063.

- ^ a b Campen C (1999). "Artistic and psychological experiments with synesthesia". Leonardo 32 (1): 9–14. doi:.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sagiv, Noam; Robertson, Lynn C (2005). Synesthesia: perspectives from cognitive neuroscience. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516623-X. OCLC 53020292.[page number needed]

- ^ a b c Ward J, Huckstep B, Tsakanikos E (February 2006). "Sound-colour synaesthesia: to what extent does it use cross-modal mechanisms common to us all?". Cortex 42 (2): 264–80. doi:. PMID 16683501.

- ^ a b Simner J, Ward J, Lanz M, et al. (2005). "Non-random associations of graphemes to colours in synaesthetic and non-synaesthetic populations.". Cognitive Neuropsychology 22 (8): 1069–1085. doi:.

- ^ a b c Rich AN, Bradshaw JL, Mattingley JB (November 2005). "A systematic, large-scale study of synaesthesia: implications for the role of early experience in lexical-colour associations". Cognition 98 (1): 53–84. doi:. PMID 16297676. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010-0277(04)00209-4.

- ^ a b Flournoy, Théodore (2001). Des phénomènes de synopsie (Audition colorée). Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 0-543-94462-X.

- ^ a b Dixon MJ, Smilek D, Merikle PM (September 2004). "Not all synaesthetes are created equal: projector versus associator synaesthetes". Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 4 (3): 335–43. doi:. PMID 15535169. http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=1530-7026&volume=4&issue=3&spage=335&aulast=Dixon.

- ^ a b Dittmar, A. (Ed.) (2007) Synästhesien. Roter Faden durchs Leben? Essen, Verlag Die Blaue Eule.

- ^ a b c "Slashdot Discussion". 2006-02-19. http://slashdot.org/comments.pl?sid=140022&cid=11726211. Retrieved on 2006-08-14.

- ^ van Campen C, Froger, C (2003). "Personal Profiles of Color Synesthesia: Developing a Testing Method for Artists and Scientists.". Leonardo 36 (4): 291–4. doi:.

- ^ Galton F (1881). "The visions of sane persons." (PDF). Fortnightly Review 29: 729–40. http://www.galton.org/essays/1880-1889/galton-1881-fort-rev-visions-sane-persons.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-06-17.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ramachandran VS and Hubbard EM (2001). "Synaesthesia: A window into perception, thought and language." (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies 8 (12): 3–34. http://psy.ucsd.edu/~edhubbard/papers/JCS.pdf.

- ^ Hubbard EM, Piazza M, Pinel P, Dehaene S (June 2005). "Interactions between number and space in parietal cortex". Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6 (6): 435–48. doi:. PMID 15928716.

- ^ Simner J, Hubbard EM (December 2006). "Variants of synesthesia interact in cognitive tasks: evidence for implicit associations and late connectivity in cross-talk theories". Neuroscience 143 (3): 805–14. doi:. PMID 16996695. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0306-4522(06)01092-X.

- ^ a b Calkins MW (1893). "A Statistical Study of Pseudo-Chromesthesia and of Mental-Forms". The American Journal of Psychology 5 (4): 439–64. doi:.

- ^ Ward J, Simner J (October 2003). "Lexical-gustatory synaesthesia: linguistic and conceptual factors". Cognition 89 (3): 237–61. doi:. PMID 12963263. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0010027703001227.

- ^ Ward J, Simner J, Auyeung V (2005). "A comparison of lexical-gustatory and grapheme-colour synaesthesia.". Cognitive Neuropsychology 22 (1): 28–41. doi:.

- ^ Gage, J. Colour and Culture. Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. (London:Thames & Hudson, 1993).

- ^ Peacock, Kenneth. "Instruments to Perform Color-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation," Leonardo 21, No. 4 (1988) 397-406.

- ^ Jewanski, J. & N. Sidler (Eds.). Farbe - Licht - Musik. Synaesthesie und Farblichtmusik. Bern: Peter Lang, 2006.

- ^ Peacock, Kenneth. "Instruments to Perform Color-Music: Two Centuries of Technological Experimentation," Leonardo 21, No. 4 (1988) 397-406.

- ^ Mahling, F. (1926) Das Problem der `audition colorée': Eine historisch-kritische Untersuchung. Archiv für die gesamte Psychologie, 57, 165-301.

- ^ Fechner, Th. (1871) Vorschule der Aesthetik. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Hartel.

- ^ Campen, Cretien van (1996). De verwarring der zintuigen. Artistieke en psychologische experimenten met synesthesie. Psychologie & Maatschappij, vol. 20, nr. 1, pp. 10-26.

- ^ Galton F (1880). "Visualized Numerals". Nature 21: 252–6. doi:.

- ^ Galton F. (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development. Macmillan. http://galton.org/books/human-faculty/. Retrieved on 2008-06-17.

- ^ Baron-Cohen S, Harrison J, Goldstein LH, Wyke M (1993). "Coloured speech perception: is synaesthesia what happens when modularity breaks down?". Perception 22 (4): 419–26. doi:. PMID 8378132.

- ^ a b c Baron-Cohen S, Burt L, Smith-Laittan F, Harrison J, Bolton P (1996). "Synaesthesia: prevalence and familiality". Perception 25 (9): 1073–9. doi:. PMID 8983047.

- ^ a b Ward J, Simner J (2005). "Is synaesthesia an X-linked dominant trait with lethality in males?". Perception 34 (5): 611–23. doi:. PMID 15991697.

- ^ a b c Asher, JE, Lamb, JA, Brocklebank, D, et al (2009). "A whole-genome scan and fine-mapping linkage study of auditory-visual synesthesia reveals evidence of linkage to chromosomes 2q24, 5q33, 6p12, and 12p12". The American Journal of Human Genetics 84: 1–7. doi:.

- ^ Smilek D, Moffatt BA, Pasternak J, White BN, Dixon MJ, Merikle PM (2002). "Synaesthesia: a case study of discordant monozygotic twins". Neurocase 8 (4): 338–42. doi:. PMID 12221147.

- ^ Smilek D, Dixon MJ, Merikle PM (October 2005). "Synaesthesia: discordant male monozygotic twins". Neurocase 11 (5): 363–70. doi:. PMID 16251137. http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&doi=10.1080/13554790500205413&magic=pubmed.

- ^ Hubbard EM, Ramachandran VS (2003). "Refining the experimental lever: A reply to Shanon and Pribram" (PDF). Journal of Consciousness Studies 10 (3): 77–84. http://psy.ucsd.edu/~edhubbard/papers/Hubbard_JCS03.pdf.

- ^ Nikolić D, Lichti P, Singer W (June 2007). "Color opponency in synaesthetic experiences". Psychol Sci 18 (6): 481–6. doi:. PMID 17576258. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0956-7976&date=2007&volume=18&issue=6&spage=481.

- ^ Ward J, Tsakanikos E, Bray A (February 2006). "Synaesthesia for reading and playing musical notes". Neurocase 12 (1): 27–34. doi:. PMID 16517513. http://www.informaworld.com/openurl?genre=article&doi=10.1080/13554790500473672&magic=pubmed.

- ^ Beeli G, Esslen M, Jäncke L (March 2005). "Synaesthesia: when coloured sounds taste sweet". Nature 434 (7029): 38. doi:. PMID 15744291.

- ^ Edquist J, Rich AN, Brinkman C, Mattingley JB (February 2006). "Do synaesthetic colours act as unique features in visual search?". Cortex 42 (2): 222–31. doi:. PMID 16683496.

- ^ Sagiv N, Heer J, Robertson L (February 2006). "Does binding of synesthetic color to the evoking grapheme require attention?". Cortex 42 (2): 232–42. doi:. PMID 16683497.

- ^ Grossenbacher PG, Lovelace CT (January 2001). "Mechanisms of synesthesia: cognitive and physiological constraints". Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 5 (1): 36–41. doi:. PMID 11164734. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1364-6613(00)01571-0.

- ^ Nunn JA, Gregory LJ, Brammer M, et al (April 2002). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging of synesthesia: activation of V4/V8 by spoken words". Nat. Neurosci. 5 (4): 371–5. doi:. PMID 11914723.

- ^ Sperling JM, Prvulovic D, Linden DE, Singer W, Stirn A (February 2006). "Neuronal correlates of colour-graphemic synaesthesia: a fMRI study". Cortex 42 (2): 295–303. doi:. PMID 16683504.

- ^ Rouw R, Scholte HS (June 2007). "Increased structural connectivity in grapheme-color synesthesia". Nat. Neurosci. 10 (6): 792–7. doi:. PMID 17515901.

- ^ Domino G (1989). "Synesthesia and Creativity in Fine Arts Students: An Empirical Look.". Creativity Research Journal 2 (1-2): 17–29.

- ^ Dailey A, Martindale C, Borkum J (1997). "Creativity, synesthesia, and physiognomic perception.". Creativity Research Journal 10 (1): 1–8. doi:.

- ^ Bruner, Jerome S.; Luria, Aleksandr Romanovich; Lurii︠a︡, A. R. (1987). The mind of a mnemonist: a little book about a vast memory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-57622-5.

- ^ Smilek D, Dixon MJ, Cudahy C, Merikle PM (2002). "Synesthetic color experiences influence memory.". Psychological Science 13 (6): 548–52. doi:.

- ^ Maurer D, Pathman T, Mondloch CJ (May 2006). "The shape of boubas: sound-shape correspondences in toddlers and adults". Dev Sci 9 (3): 316–22. doi:. PMID 16669803. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=1363-755X&date=2006&volume=9&issue=3&spage=316.

- ^ Gray JA, Chopping S, Nunn J et al. (2002). "Implications of synaesthesia for functionalism: Theory and experiments". Journal of Consciousness 9 (12): 5–31.

- ^ Berman G (1999). "Synesthesia and the Arts". Leonardo 32 (1): 15–22. doi:.

- ^ Maur, Karin von (1999). The Sound of Painting: Music in Modern Art (Pegasus Library). Munich: Prestel. ISBN 3-7913-2082-3.

- ^ Gage, John D. (1993). Colour and culture: practice and meaning from antiquity to abstraction. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27818-0.

- ^ Gage, John D. (1999). Color and meaning: art, science, and symbolism. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22611-9.

- ^ Campen, Cretien van (2009) Visual Music and Musical Paintings. The Quest for Synesthesia in the Arts. In: F. Bacci & D. Melcher. Making Sense of Art, making Art of Sense. Oxford: Oxford University Press (forthcoming).

- ^ Steen, C. (2001). Visions Shared: A Firsthand Look into Synesthesia and Art, Leonardo, Vol. 34, No. 3, Pages 203-208 (doi:10.1162/002409401750286949)

- ^ Marcia Smilack Website Accessed 20 Aug 2006.

- ^ E-text of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, see p. 86.

- ^ see Cytowic, Richard E. 2002. Synaesthesia: a Union of the Senses. Second edition. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ^ Nabokov, Vladimir. 1966. Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited. New York: Putnam.

- ^ Ellington, as quoted in George, Don. 1981. Sweet man: The real Duke Ellington. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. Page 226.

- ^ Quoted from an anonymous article in the Neuen Berliner Musikzeitung (29 August, 1895); quoted in Mahling, Friedrich. 1926. "Das Problem der 'Audition colorée: Eine historische-kritische Untersuchung." Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie; LVII Band. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft M.B.H. Pp. 165-301. Page 230. Translation by Sean A. Day.

- ^ This is according to an article in the Russian press, Yastrebtsev V. "On N.A.Rimsky-Korsakov's color sound- contemplation." Russkaya muzykalnaya gazeta, 1908, N 39-40, p. 842-845 (in Russian), cited by Bulat Galeyev (1999).

- ^ see Samuel, Claude. 1994 (1986). Olivier Messiaen: Music and Color. Conversations with Claude Samuel. Translated by E. Thomas Glasow. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press.

- ^ Feynman, Richard. 1988. What Do You Care What Other People Think? New York: Norton. P. 59.

- ^ Tammet, Daniel (2006). Born on a Blue Day. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0340899748.

- ^ Morely Safer (28 January 2007). "Brain Man". CBS News. http://cbsnews.com/stories/2007/01/26/60minutes/main2401846.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-02-02.

- ^ It just always stuck out in my mind, and I could always see it. I don't know if that makes sense, but I could always visualize what I was hearing... Yeah, it was always like weird colors." From a Nightline interview with Pharrell

- ^ a b Dann, Kevin T. (1998). Bright colors falsely seen: synaesthesia and the search for transcendental knowledge. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-06619-8.

- ^ B. M. Galeyev and I. L. Vanechkina (August 2001). "Was Scriabin a Synesthete?". Leonardo; Vol. 34, Issue 4, pp. 357 - 362.

[edit] External links

| This article's external links may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessive or inappropriate external links. |

[edit] Synesthesia associations

- American Synesthesia Association

- Australian Synaesthesia Association

- Belgian Synesthesia Association

- UK Synaesthesia Association

- German Synaesthesia Association | Deutsche Synästhesie-Gesellschaft e.V. (in German)

[edit] Community sites

- Synaesthete.com A forum for synesthetes and people interested in synesthesia, with a special section for teenage synesthetes.

- Synesthesia in Art and Science Bibliography compiled by Cretien van Campen for Leonardo/ISAST

- The Nexus@MixSig.net: a forum with discussions concerning many different types of synesthesia

- Blue Cats Resource Center by Patricia Lynne Duffy

- A community of synesthetes on livejournal.com

- The Synesthesia List; an e-mail forum for synesthtetes and researchers

[edit] Scientific resources

- The Synesthesia Battery: take the tests to discover if you are synesthetic. Developed by David Eagleman.

- Richard E. Cytowic Downloads and information.

- Edward M. Hubbard Synesthesia research including pdf versions of scientific articles.

- Synesthetics by Cretien van Campen Info on artistic and scientific experiments with synesthesia, gives the historical background.

- Jamie Ward Synaesthesia researcher, based in the UK, useful information and links to articles.

- Synaesthesia and Education: a research project at the University of Cambridge investigating the effects of grapheme-colour synesthesia on numerical processing in children.

- Museums of the Mind, a synesthesia portal by Dr. Hugo Heyrman, more specific on the interaction between art and synesthesia.

- Synesthesiograph

- Synaesthesia.com with Onlinetest, Homepage about Synaesthesia (English/Deutsch) by Marc Jacques Mächler

[edit] Scientific articles on the web

- Scientific American article Hearing Colors, Tasting Shapes (PDF version) by Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Edward M. Hubbard, May 2003.

- Cortex: Special Issue on Cognitive Neuroscience Perspectives on Synesthesia The neuroscience journal Cortex presents a special issue focusing on modern scientific research of synesthesia.

- Campen, Cretien van (2009), The Hidden Sense: On Becoming Aware of Synesthesia, TECCOGS , vol. 1, pp. 1-13.

[edit] Popular press

- For Some, the Words Just Roll Off the Tongue New York Times article on lexical-gustatory synesthesia. November 22, 2006. New York Times.

- World Science: Paintings really can be heard, scientist says World Science's article on hearing colours. Sept. 7, 2006. Courtesy University College London and World Science staff

- Seeing life in colors: Cross-wired senses on ABC Primetime. 15 August 2006

- Why some see colours in numbers at BBC News, 24 March 2005

- People who feel color gets scientific acceptance

- synesthesia and psychic auras

- Infantile synesthesia

- Mirror Writing could be linked to synesthesia

- Synaesthesia and Migraine Synesthesia may occur as a visual migraine aura.

- A Brief History of Synesthesia and Music

- Hearing Pictures, Seeing Sounds., Experiencing Justin Lassen's World, Feature on CGSociety (May 2006).

- Study: People Literally Feel Pain of Others - mirror-touch synesthesia Live Science, 17 June 2007, by Charles Q. Choi.

- Words on the tips of their tongues – words triggering taste sensations (Cosmos Magazine, 23 November 2006)

- TED Talks: V. Ramachandran lecture on synesthesia