Fingerprint

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Forensic science |

|---|

| Physiological sciences |

| Forensic pathology · Forensic dentistry |

| Forensic anthropology · Forensic entomology · Forensic archaeology |

| Social sciences |

| Forensic psychology · Forensic psychiatry |

| Other specializations |

| Fingerprint analysis · Forensic accounting |

| Ballistics · Bloodstain pattern analysis · Body identification |

| DNA profiling · Forensic arts · Forensic toxicology |

| Forensic footwear evidence |

| Questioned document examination |

| Cybertechnology in forensics |

| Information forensics · Computer forensics |

| Related disciplines |

| Forensic engineering |

| Forensic materials engineering |

| Forensic polymer engineering |

| Fire investigation |

| Vehicular accident reconstruction |

| People in Forensics |

| Auguste Ambroise Tardieu |

| Edmond Locard |

| Bill Bass |

| Related articles |

| Crime scene · CSI Effect |

| Trace evidence · Skid mark |

| Use of DNA in forensic entomology |

A fingerprint is an impression of the friction ridges of all part of the finger.[1] A friction ridge is a raised portion of the epidermis on the palmar (palm) or digits (fingers and toes) or plantar (sole) skin, consisting of one or more connected ridge units of friction ridge skin.[1] These are sometimes known as "dermal ridges" or "dermal papillae". These ridges assist in gripping objects and may also serve to amplify vibrations triggered when fingertips brush across an uneven surface, better transmitting the signals to sensory nerves involved in fine texture perception.[2]

Fingerprints may be deposited in natural secretions from the eccrine glands present in friction ridge skin (secretions consisting primarily of water) or they may be made by ink or other contaminants transferred from the peaks of friction skin ridges to a relatively smooth surface such as a fingerprint card.[3] The term fingerprint normally refers to impressions transferred from the pad on the last joint of fingers and thumbs, though fingerprint cards also typically record portions of lower joint areas of the fingers (which are also used to make identifications).

Contents |

[edit] Fingerprints as used for identification

Fingerprint identification (sometimes referred to as dactyloscopy[4]) or palmprint identification is the process of comparing questioned and known friction skin ridge impressions (see Minutiae) from fingers or palms or even toes to determine if the impressions are from the same finger or palm. The flexibility of friction ridge skin means that no two finger or palm prints are ever exactly alike (never identical in every detail), even two impressions recorded immediately after each other. Fingerprint identification (also referred to as individualization) occurs when an expert (or an expert computer system operating under threshold scoring rules) determines that two friction ridge impressions originated from the same finger or palm (or toe, sole) to the exclusion of all others.

A known print is the intentional recording of the friction ridges, usually with black printers ink rolled across a contrasting white background, typically a white card. Friction ridges can also be recorded digitally using a technique called Live-Scan. A latent print is the chance reproduction of the friction ridges deposited on the surface of an item. Latent prints are often fragmentary and may require chemical methods, powder, or alternative light sources in order to be visualized.

When friction ridges come in contact with a surface that is receptive to a print, material on the ridges, such as perspiration, oil, grease, ink, etc. can be transferred to the item. The factors which affect friction ridge impressions are numerous, thereby requiring examiners to undergo extensive and objective study in order to be trained to competency. Pliability of the skin, deposition pressure, slippage, the matrix, the surface, and the development medium are just some of the various factors which can cause a latent print to appear differently from the known recording of the same friction ridges. Indeed, the conditions of friction ridge deposition are unique and never duplicated. This is another reason why extensive and objective study is necessary for examiners to achieve competency.

[edit] Fingerprint types

[edit] Latent prints

Although the word latent means hidden or invisible, in modern usage for forensic science the term latent prints means any chance of accidental impression left by friction ridge skin on a surface, regardless of whether it is visible or invisible at the time of deposition. Electronic, chemical and physical processing techniques permit visualization of invisible latent print residue whether they are from natural secretions of the eccrine glands present on friction ridge skin (which produce palmar sweat, consisting primarily of water with various salts and organic compounds in solution), or whether the impression is in a contaminant such as motor oil, blood, paint, ink, etc.

Latent prints may exhibit only a small portion of the surface of the finger and may be smudged, distorted, overlapping, or any combination, depending on how they were deposited. For these reasons, latent prints are an “inevitable source of error in making comparisons,” as they generally “contain less clarity, less content, and less undistorted information than a fingerprint taken under controlled conditions, and much, much less detail compared to the actual patterns of ridges and grooves of a finger.”[5]

[edit] Patent prints

These are friction ridge impressions of unknown origins which are obvious to the human eye and are caused by a transfer of foreign material on the finger, onto a surface. Because they are already visible they need no enhancement, and are generally photographed instead of being lifted in the same manner as latent prints.[citation needed] Finger deposits can include materials such as ink, dirt, or blood onto a surface.

[edit] Plastic prints

A plastic print is a friction ridge impression from a finger or palm (or toe/foot) deposited in a material that retains the shape of the ridge detail.[6] Commonly encountered examples are melted candle wax, putty removed from the perimeter of window panes and thick grease deposits on car parts. Such prints are already visible and need no enhancement, but investigators must not overlook the potential that invisible latent prints deposited by accomplices may also be on such surfaces. After photographically recording such prints, attempts should be made to develop other non-plastic impressions deposited at natural finger/palm secretions (eccrine gland secretions) or contaminates.

[edit] Fingerprint capture and detection

[edit] Livescan devices

Fingerprint image acquisition is considered the most critical step of an automated fingerprint authentication system, as it determines the final fingerprint image quality, which has drastic effects on the overall system performance. There are different types of fingerprint readers on the market, but the basic idea behind each capture approach is to measure in some way the physical difference between ridges and valleys. All the proposed methods can be grouped in two major families: solid-state fingerprint readers and optical fingerprint readers. The procedure for capturing a fingerprint using a sensor consists of rolling or touching with the finger onto a sensing area, which according to the physical principle in use (capacitive, optical, thermal, etc.) captures the difference between valleys and ridges. When a finger touches or rolls onto a surface, the elastic skin deforms. The quantity and direction of the pressure applied by the user, the skin conditions and the projection of an irregular 3D object (the finger) onto a 2D flat plane introduce distortions, noise and inconsistencies in the captured fingerprint image. These problems result in inconsistent, irreproducible and non-uniform contacts[citation needed] and, during each acquisition, their effects on the same fingerprint results are different and uncontrollable. The representation of the same fingerprint changes every time the finger is placed on the sensor platen, increasing the complexity of the fingerprint matching, impairing the system performance, and consequently limiting the widespread use of this biometric technology.

[edit] Methods of Fingerprint Detection

Since the late nineteenth century, fingerprint identification methods have been used by police agencies around the world to identify both suspected criminals as well as the victims of crime. The basis of the traditional fingerprinting technique is simple. The skin on the palmar surface of the hands and feet forms ridges, so-called papillary ridges, in patterns that are unique to each individual and which do not change over time. Even identical twins (who share their DNA) do not have identical fingerprints. Fingerprints on surfaces may be described as patent or latent. Patent fingerprints are left when a substance (such as paint, oil or blood) is transferred from the finger to a surface and are easily photographed without further processing. Latent fingerprints, in contrast, occur when the natural secretions of the skin are deposited on a surface through fingertip contact, and are usually not readily visible. The best way to render latent fingerprints visible, so that they can be photographed, is complex and depends, for example, on the type of surface involved. It is generally necessary to use a ‘developer’, usually a powder or chemical reagent, to produce a high degree of visual contrast between the ridge patterns and the surface on which the fingerprint was left.

Developing agents depend on the presence of organic materials or inorganic salts for their effectiveness although the water deposited may also take a key role. Fingerprints are typically formed from the aqueous based secretions of the eccrine glands of the fingers and palms with additional material from sebaceous glands primarily from the forehead. The latter contamination results from the common human behaviors of touching the face and hair.

The resulting latent fingerprints consist usually of a substantial proportion of water with small traces of amino acids, chlorides etc mixed with a fatty, sebaceous component which contains a number of fatty acids, triglycerides etc Detection of the small proportion of reactive organic material such as urea and amino acids is far from easy.

Crime scene fingerprints may be detected by simple powders, or some chemicals applied at the crime scene; or more complex, usually chemical techniques applied in specialist laboratories to appropriate articles removed from the crime scene. With advances in these more sophisticated techniques some of the more advanced crime scene investigation services from around the world are now reporting that 50% or more of the total crime scene fingerprints result from these laboratory based techniques

Although there are hundreds of reported techniques for fingerprint detection many are only of academic interest and there are only around 20 really effective methods which are currently in use in the more advanced fingerprint laboratories around the world. Some of these techniques such as Ninhydrin, Diazofluorenone, and Vacuum Metal Deposition show quite surprising sensitivity and are used operationally to great effect. Some fingerprint reagents are specific, for example Ninhydrin or Diazo-fluorenone reacting with amino acids. Others such as ethyl cyanoacrylate polymerisation, work apparently by water based catalysis and polymer growth. Vacuum metal deposition using gold and zinc has been shown to be non-specific but detect fat layers as thin as one molecule. More mundane methods such as application of fine powders work by adhesion to sebaceous deposits and possibly aqueous deposits for fresh fingerprints. The aqueous component whilst initially sometimes making up over 90% of the weight of the fingerprint can evaporate quite quickly and most may be gone in after 24 hours. After work by Duff and Menzel on the use of Argon Ion lasers for fingerprint detection a wide range of fluorescence techniques have been introduced, primarily for the enhancement of chemically developed fingerprints but also some detection of inherent fluorescence of the latent fingerprints. The most comprehensive manual of operational methods of fingerprint development is published by the UK Home Office Scientific Development Branch http://scienceandresearch.homeoffice.gov.uk/hosdb/fingerprints-footwear-marks/ and is used widely around the world.

The International Fingerprint Research Group (IFRG) which meets biennially, consisting of members of the leading fingerprint research groups from Europe, the US, Canada, Australia and Israel leads the way in the development, assessment and implementation of new techniques for operational fingerprint detection.

One problem is the fact that the organic component of any deposited material is readily destroyed by heat, such as occurs when a gun is fired or a bomb is detonated, when the temperature may reach as high as 500°C. In contrast, the non-volatile, inorganic component of eccrine secretion remains intact even when exposed to temperatures as high as 600°C.

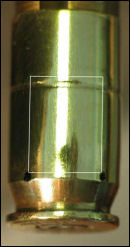

Within the Materials Research Centre, University of Swansea, UK [3], University of Swansea, UK, Professor Neil McMurray and Dr Geraint Williams have developed a technique that enables fingerprints to be visualised on metallic and electrically conductive surfaces without the need to develop the prints first. The technique involves the use of an instrument called a scanning Kelvin probe (SKP), which measures the voltage, or electrical potential, at pre-set intervals over the surface of an object on which a fingerprint may have been deposited. These measurements can then be mapped to produce an image of the fingerprint. A higher resolution image can be obtained by increasing the number of points sampled, but at the expense of the time taken for the process. A sampling frequency of 20 points per mm is high enough to visualise a fingerprint in sufficient detail for identification purposes and produces a voltage map in 2–3 hours. So far the technique has been shown to work effectively on a wide range of forensically important metal surfaces including iron, steel and aluminium. While initial experiments were performed on planar, i.e. flat, surfaces, the technique has been further developed to cope with severely non-planar surfaces, such as the warped cylindrical surface of fired cartridge cases. The very latest research from the department has found that physically removing a fingerprint from a metal surface, e.g. by rubbing with a tissue, does not necessarily result in the loss of all fingerprint information. The reason for this is that the differences in potential that are the basis of the visualisation are caused by the interaction of inorganic salts in the fingerprint deposit and the metal surface and begin to occur as soon as the finger comes into contact with the metal, resulting in the formation of metal – ion complexes that cannot easily be removed.

Currently, in crime scene investigations, a decision has to be made at an early stage whether to attempt to retrieve fingerprints through the use of developers or whether to swab surfaces in an attempt to salvage material for DNA fingerprinting. The two processes are mutually incompatible, as fingerprint developers destroy material that could potentially be used for DNA analysis, and swabbing is likely to make fingerprint identification impossible.

The application of the new SKP fingerprinting technique, which is non-contact and does not require the use of developers, has the potential to allow fingerprints to be retrieved while still leaving intact any material that could subsequently be subjected to DNA analysis. The University of Swansea group hope to have a forensically usable prototype in the near future and it is intended that eventually the instrument will be manufactured in sufficiently large numbers that it will be widely used by forensic teams on the frontline.

There has recently been significant worldwide interest in the technique with articles appearing in/on BBC.co.uk[4], Sky News[5] [6], S4C news, The Daily Mail, FHM magazine, AOL, Yahoo news, Telegraph.co.uk, The Hindu, Taipei times, Sydney Morning Herald, San Francisco Gate, The Mercury (South Africa), Brisbane Courier Mail and many others. There has also been significant interest from the Home Office and a number of different police forces across the UK.

More information about the technique has been published in a number of scientific journals[7] [8].

[edit] Classifying fingerprints

Before computerization replaced manual filing systems in large fingerprint operations, manual fingerprint classification systems were used to categorize fingerprints based on general ridge formations (such as the presence or absence of circular patterns in various fingers), thus permitting filing and retrieval of paper records in large collections based on friction ridge patterns independent of name, birth date and other biographic data that persons may misrepresent. The most popular ten-print classification systems include the Roscher system, the Vucetich system, and the Henry Classification System. Of these systems, the Roscher system was developed in Germany and implemented in both Germany and Japan, the Vucetich system was developed in Argentina and implemented throughout South America, and the Henry system was developed in India and implemented in most English-speaking countries.[7]

In the Henry system of classification, there are three basic fingerprint patterns: Arch, Loop and Whorl.[8] There are also more complex classification systems that further break down patterns to plain arches or tented arches.[7] Loops may be radial or ulnar, depending on the side of the hand the tail points towards. Whorls also have sub-group classifications including plain whorls, accidental whorls, double loop whorls, peacock's eye, accidental, composite, and central pocket loop whorls.[7]

[edit] Footprints

Friction ridge skin present on the soles of the feet and toes (plantar surfaces) is as unique as ridge detail on the fingers and palms (palmar surfaces). When recovered at crime scenes or on items of evidence, sole and toe impressions are used in the same manner as finger and palm prints to effect identifications. Footprint (toe and sole friction ridge skin) evidence has been admitted in U.S. courts since 1934 (People v. Les, 267 Michigan 648, 255 NW 407).

Footprints of infants, along with thumb or index finger prints of mothers, are still commonly recorded in hospitals to assist in verifying the identity of infants. Often, the only identifiable ridge detail in such impressions is from the large toe or adjacent to the large toe, due to the difficulty of recording such fine detail. When legible ridge detail is lacking, DNA is normally effective (except in instances of chimaerism) for indirectly identifying infants by confirming maternity and paternity of an infant's parents.

It is not uncommon for military records of flight personnel to include bare foot inked impressions. Friction ridge skin protected inside flight boots tends to survive the trauma of a plane crash (and accompanying fire) better than fingers. Even though the U.S. Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory (AFDIL) stores refrigerated DNA samples from all current active duty and reserve personnel, almost all casualty identifications are effected using fingerprints from military ID card records (live scan fingerprints are recorded at the time such cards are issued). When friction ridge skin is not available from deceased military personnel, DNA and dental records are used to confirm identity.

[edit] Lifestyle information

The secretions, skin oils and dead cells in the fingerprint contain residues of various chemicals and their metabolites present in the body. These can be detected and used for forensic purposes. For example the fingerprints of tobacco smokers contain traces of cotinine, a nicotine metabolite; they also contain traces of nicotine itself; however that may be ambiguous as its presence may be caused by mere contact of the finger with a tobacco product. By treating the fingerprint with gold nanoparticles with attached cotinine antibodies, and then subsequently with fluorescent agent attached to cotinine antibody antibodies, a fingerprint of a smoker becomes fluorescent; non-smoker's fingerprint stays dark. The same approach is investigated to be used for identifying heavy coffee drinkers, cannabis smokers, and users of various other drugs. [9] [10]

[edit] U.S. databases and compression

The FBI manages a fingerprint identification system and database called IAFIS, which currently holds the fingerprints and criminal records of over fifty-one million criminal record subjects, and over 1.5 million civil (non-criminal) fingerprint records. U.S. Visit currently holds a repository of over 50 million persons, primarily in the form of two-finger records (by 2008, U.S. Visit is transforming to a system recording FBI-standard tenprint records).

Most American law enforcement agencies use Wavelet Scalar Quantization (WSQ), a wavelet-based system for efficient storage of compressed fingerprint images at 500 pixels per inch (ppi). WSQ was developed by the FBI, the Los Alamos National Lab, and the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). For fingerprints recorded at 1000 ppi spatial resolution, law enforcement (including the FBI) uses JPEG 2000 instead of WSQ.

[edit] History and validity

[edit] History of fingerprinting for identification

Fingerprints have been found on ancient Babylonian clay tablets, seals, and pottery[9][10][11][12]. They have also been found on the walls of Egyptian tombs and on Minoan, Greek, and Chinese pottery — as well as on bricks and tiles in Babylon and Rome. Some of these fingerprints were deposited unintentionally by workers during fabrication; sometimes the fingerprints served as decoration. However, on some pottery, fingerprints were impressed so deeply that they were likely intended to serve as the equivalent of a brand label.

Fingerprints were also used as substitutes for signatures. In Babylon from 1885-1913 B.C.E., in order to protect against forgery, parties to a legal contract impressed their fingerprints into the clay tablet on which the contract had been written. By 246 B.C.E., Chinese officials impressed their fingerprints in clay seals, which were used to seal documents. With the advent of silk and paper in China, parties to a legal contract impressed their handprints on the document. Sometime before 851 C.E., an Arab merchant in China, Abu Zayd Hasan, witnessed Chinese merchants using fingerprints to authenticate loans.[13] By 702 C.E., Japan had adopted the Chinese practice of sealing contracts with fingerprints. Supposedly, in 14th century Persia, government documents were authenticated with thumbprints.

Although the ancient peoples probably did not realize that fingerprints could identify individuals,[14] references from the age of the Babylonian king Hammurabi (1792-1750 B.C.E.) indicate that law officials fingerprinted people who had been arrested.[15] In China around 300 C.E. handprints were used as evidence in a trial for theft. In 650 C.E., the Chinese historian Kia Kung-Yen remarked that fingerprints could be used as a means of authentication.[16] In his Jami al-Tawarikh [Universal History], Persian official and physician Rashid-al-Din Hamadani (a.k.a. "Rashideddin") (1247-1318) comments on the Chinese practice of identifying people via their fingerprints: "Experience shows that no two individuals have fingers exactly alike."[17]

A list of significant modern dates documenting the use of fingerprints for positive identification are as follows[18]:

- 1684: Nehemiah Grew (1641-1712, English physician, botanist, and microscopist) published the first paper on the ridge structure of skin of the fingers and palms.[19] In 1685, Govard Bidloo (1649-1713, Dutch physician)[20] and Marcello Malpighi (1628-1694, Italian physician)[21] published books on anatomy which also illustrated the ridge structure of the fingers.

- 1788: Johann Christoph Andreas Mayer[22] (1747-1801, German anatomist) recognized that fingerprints are unique to each individual.[23]

- 1823: Jan Evangelista Purkyně, a professor of anatomy at the University of Breslau, published his thesis discussing 9 fingerprint patterns, but he did not mention the use of fingerprints to identify persons.[24]

- 1853: Georg von Meissner (1829-1905, German anatomist) studied friction ridges.[25]

- 1858: Sir William James Herschel (1833-1918, English magistrate) initiated fingerprinting in India.[26]

- 1880: Dr Henry Faulds published his first paper on the subject in the scientific journal Nature in 1880.[27] Returning to the UK in 1886, he offered the concept to the Metropolitan Police in London but it was dismissed.[28][29]

- 1892: Sir Francis Galton published a detailed statistical model of fingerprint analysis and identification and encouraged its use in forensic science in his book Finger Prints.[30]

- 1892: Juan Vucetich, an Argentine police officer who had been studying Galton pattern types for a year, made the first criminal fingerprint identification. He successfully proved Francisca Rojas guilty of murder after showing that the bloody fingerprint found at the crime scene was hers, and could only be hers.

- 1897: The world's first Fingerprint Bureau opened in Calcutta (Kolkata), India after the Council of the Governor General approved a committee report (on 12 June 1897) that fingerprints should be used for classification of criminal records. Working in the Calcutta Anthropometric Bureau (before it became the Fingerprint Bureau) were Azizul Haque and Hem Chandra Bose. Haque and Bose were the Indian fingerprint experts credited with primary development of the fingerprint classification system eventually named after their supervisor, Sir Edward Richard Henry.[31][32]

- 1901: The first United Kingdom Fingerprint Bureau was founded in Scotland Yard. The Henry Classification System, devised by Sir Edward Richard Henry with the help of Haque and Bose was accepted in England and Wales.

- 1902: Dr. Henry P. DeForrest used fingerprinting in the New York Civil Service.

- 1906: New York City Police Department Deputy Commissioner Joseph A. Faurot introduced fingerprinting of criminals to the United States.

[edit] Validity of fingerprinting for identification

The validity of forensic fingerprint evidence has recently been challenged by academics, judges and the media. While fingerprint identification was an improvement over earlier anthropometric systems, the subjective nature of matching, despite a very low error rate, has made this forensic practice controversial. [33]

Certain specific criticisms are now being accepted by some leaders of the forensic fingerprint community, providing an incentive to improve training and procedures. Glenn Langenburg who is a Forensic Scientist, Latent Print Examiner for the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, is such an individual, having written an article that responds to the most active academic critics.

[edit] Criticism

The words "reliability" and "validity" have specific meanings to the scientific community. Reliability means successive tests bring the same results. Validity means that the results accurately reflect the external criteria being measured.

Although experts are often more comfortable relying on their instincts, this reliance does not always translate into superior predictive ability. For example, in the popular Analysis, Comparison, Evaluation, and Verification (ACE-V) paradigm for fingerprint identification, the verification stage, in which a second examiner confirms the assessment of the original examiner, may increase the consistency of the assessments. But while the verification stage has implications for the reliability of latent print comparisons, it does not assure their validity.(pp 12)[5]

The few tests of validity of forensic fingerprinting have not been supportive of the method:

Despite the absence of objective standards, scientific validation, and adequate statistical studies, a natural question to ask is how well fingerprint examiners actually perform. Proficiency tests do not validate a procedure per se, but they can provide some insight into error rates. In 1995, the Collaborative Testing Service (CTS) administered a proficiency test that, for the first time, was “designed, assembled, and reviewed” by the International Association for Identification (IAI).The results were disappointing. Four suspect cards with prints of all ten fingers were provided together with seven latents. Of 156 people taking the test, only 68 (44%) correctly classified all seven latents. Overall, the tests contained a total of 48 incorrect identifications. David Grieve, the editor of the Journal of Forensic Identification, describes the reaction of the forensic community to the results of the CTS test as ranging from “shock to disbelief,” and added:

Errors of this magnitude within a discipline singularly admired and respected for its touted absolute certainty as an identification process have produced chilling and mind- numbing realities. Thirty-four participants, an incredible 22% of those involved, substituted presumed but false certainty for truth. By any measure, this represents a profile of practice that is unacceptable and thus demands positive action by the entire community.

What is striking about these comments is that they do not come from a critic of the fingerprint community, but from the editor of one of its premier publications.(pp25)[5]

[edit] Defense

Fingerprints collected at a crime scene, or on items of evidence from a crime, can be used in forensic science to identify suspects, victims and other persons who touched a surface. Fingerprint identification emerged as an important system within police agencies in the late 19th century, when it replaced anthropometric measurements as a more reliable method for identifying persons having a prior record, often under an alias name, in a criminal record repository.[4]

The science of fingerprint identification can assert its standing amongst forensic sciences for many reasons, including the following:

- Has served all governments worldwide during the past 100 years to provide accurate identification of criminals. No two fingerprints have ever been found identical in many billions of human and automated computer comparisons. Fingerprints are the very basis for criminal history foundation at every police agency.[4]

- Established the first forensic professional organization, the International Association for Identification (IAI), in 1915.[34]

- Established the first professional certification program for forensic scientists, the IAI's Certified Latent Print Examiner program (in 1977), issuing certification to those meeting stringent criteria and revoking certification for serious errors such as erroneous identifications.[35]

- Remains the most commonly used forensic evidence worldwide — in most jurisdictions fingerprint examination cases match or outnumber all other forensic examination casework combined.

- Continues to expand as the premier method for identifying persons, with tens of thousands of persons added to fingerprint repositories daily in America alone — far outdistancing similar databases in growth.

- Is claimed to outperform DNA and all other human identification systems (fingerprints are said to solve ten times more unknown suspect cases than DNA in most jurisdictions).

- Fingerprint identification was the first forensic discipline (in 1977) to formally institute a professional certification program for individual experts, including a procedure for decertifying those making errors. Other forensic disciplines later followed suit in establishing certification programs whereby certification could be revoked for error.[35]

Fingerprint identification effects far more positive identifications of persons worldwide daily than any other human identification procedure. Some of the discontent over fingerprint evidence may be due to the desire to push the conclusiveness of fingerprint examinations to the same level of certitude as that of DNA analysis. DNA is probability-based inasmuch as an individual is genetically half from the mother's contribution and half from the father's contribution. These genetic contributions are passed down from generation to generation. While pattern type (arch, loops, and whorls) may be inherited, the details of the friction ridges are not. For example, it cannot be concluded that a person inherited a certain bifurcation from their mother and an ending ridge from their father as the development of these features are completely random. Further, fingerprints as an analogy of uniqueness has been widely scientifically accepted. For example, chemists often use the term "fingerprint region" to describe an area of a chemical that can be used to identify it.

Another criticism sometimes leveled at fingerprint practice is that it is a "closed discipline". However, practitioners in the scientific community are generally specialized and may not extend to other areas of science; in this respect, fingerprint scientists are no different from the rest of the scientific community. The fingerprint community asserts that it maintains the need for objectivity and continued research in the area of friction ridge analysis.

[edit] Errors in identification or processing

Below are cases of errors in fingerprint identification; however, some cases involved misfiling of fingerprints or suspect profiling which slanted interpretation, rather than faults by objective matches from fingerprint search technology.

[edit] William West

A story that some regard as apocryphal circulates about events occurring in the early 20th century when a man was spotted in the incoming prisoner line at the U.S. Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas by a guard who recognized him and thought he was already in the prison population. Upon examination, the incoming prisoner claimed to be named Will West, while the existing prisoner was named William West. According to their Bertillon measurements, they were essentially indistinguishable. Only their fingerprints could readily identify them, and the Bertillon Method was discredited.

There is evidence that men named Will and William West were both imprisoned in the Federal Penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas, between 1903 and 1909. However, the details of the case are suspicious, especially since they differ between retells, and the story did not appear in print until 1918. Today, people familiar with the story differ on whether the story was accurate, a case of people (possibly separated twins) who bore a striking resemblance, a case of known twins, or complete fiction. The story of Will West is mentioned on page 167 of Forensic Uses of Digital Imaging by John C. Russ, with mug shots of "the two Will Wests" on page 168.

It should be noted that the West case is not a case of fingerprint error, but an error in the method of anthropometry, which the fingerprint science replaced.

[edit] Brandon Mayfield and Madrid bombing

Error in identification: Brandon Mayfield is an Oregon lawyer who was identified as a participant in the Madrid bombing based on a so-called fingerprint match by the FBI.[36] The FBI Latent Print Unit ran the print collected in Madrid and reported a match against one of 20 fingerprint candidates returned in a search response from their IAFIS — Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System. The FBI initially called the match "100 percent positive" and an "absolutely incontrovertible match". The Spanish National Police examiners concluded the prints did not match Mayfield, and after two weeks identified another man who matched. The FBI acknowledged the error, and a judge released Mayfield after two weeks in May 2004.[36] In January of 2006, a U.S. Justice Department report was released which faulted the FBI for sloppy work but exonerated them of more serious allegations. The report found that misidentification was due to misapplication of methodology by the examiners involved: Mayfield is an American-born convert[36] to Islam and his wife is an Egyptian immigrant,[36] not factors that affect fingerprint search technology.

On 29 November 2006, the FBI agreed to pay Brandon Mayfield the sum of US$2 million.[36] The judicial settlement allows Mayfield to continue a suit regarding certain other government practices surrounding his arrest and detention. The formal apology stated that the FBI, which erroneously linked him to the 2004 Madrid bombing through a fingerprinting mistake, had taken steps to "ensure that what happened to Mr. Mayfield and the Mayfield family does not happen again."[36]

[edit] René Ramón Sánchez

Error in "Clerical" processing. René Ramón Sánchez, a legal Dominican Republic immigrant was booked on a DUI charge on July 15, 1995. He had his fingerprints affixed on a card containing the name, Social Security number and other data for Leo Rosario, who was being processed at the same time. Leo Rosario was arrested for selling cocaine to an undercover police officer. In August of 1998, Sanchez was stopped again by police officers, for DUI in Manhattan. René was then identified as Leo Rosario on October 11, 2000, while returning from a visit to relatives in the Dominican Republic. He was arrested at Kennedy International Airport. Even though he did not match the physical description of Rosario, the fingerprints were considered more reliable.[37]

[edit] Shirley McKie

Error in identification. Shirley McKie was a police detective in 1997 when she was accused of leaving her thumb print inside a house in Kilmarnock, Scotland where Marion Ross had been murdered. Although detective constable McKie denied having been inside the house, she was arrested in a dawn raid the following year and charged with perjury. The only evidence was the thumb print allegedly found at the murder scene. Two American experts testified on her behalf at her trial in May 1999 and she was found not guilty. The Scottish Criminal Record Office (SCRO) would not admit any error, but Scottish first minister Jack McConnell later said there had been an "honest mistake".

On February 7, 2006, McKie was awarded £750,000 in compensation from the Scottish Executive and the SCRO.[11] Controversy continues to surround the McKie case with calls for the resignations of Scottish ministers and for either a public or a judicial inquiry into the matter.[12]

[edit] Stephan Cowans

Error in identification. Stephan Cowans (d. 2007-10-25)[38] was convicted of attempted murder in 1997 after he was accused of the shooting of a police officer while fleeing a robbery in Roxbury, Massachusetts. He was implicated in the crime by the testimony of two witnesses, one of whom was the victim. The other evidence was a fingerprint on a glass mug that the assailant drank water from, and experts testified that the fingerprint belonged to him. He was found guilty and sent to prison with a sentence of 35 years. While in prison he earned money cleaning up biohazards until he could afford to have the evidence tested for DNA. The DNA did not match his, but he had already served six years in prison before he was released.

[edit] Privacy issues

[edit] Fingerprinting of children

Various schools have implemented fingerprint locks or registered children's fingerprints. This happened in the United Kingdom (fingerprint lock in the Holland Park School in London,[39] databases, etc.),[40] in Belgium (école Marie-José in Liège[41][42]), in France, in Italy, etc. The NGO Privacy International has alerted that tens of thousands of UK school children were being fingerprinted by schools, often without the knowledge or consent of their parents.[43] In 2002, the supplier Micro Librarian Systems, which use a technology similar to US prisons and German military, estimated that 350 schools through-out Britain were using such systems, to replace library cards.[43] In 2007, it is estimated that 3 500 schools (ten times more) are using such systems.[44] Under the Data Protection Act (DPA), schools in the UK do not have to ask parental consent for such practices. Parents opposed to such practices may only bring individual complaints against schools.[45]

In Belgium, this practice gave rise to a question in Parliament on February 6, 2007 by Michel de La Motte (Humanist Democratic Centre) to the Education Minister Marie Arena, who replied that they were legal insofar as the school did not use them for external purposes nor to survey the private life of children.[46] Such practices have also been used in France (Angers, Carqueiranne college in the Var — the latter won the Big Brother Award of 2005, etc.) although the CNIL, official organisation in charge of protection of privacy, has declared them "disproportionate."[47]

In March 2007, the British government was considering fingerprinting of children aged 11 to 15 as part of new passport and ID card (the latter having been recently implemented in the UK), also lifting opposition for privacy concerns. All fingerprints taken would be cross-checked against prints from 900,000 unsolved crimes. Shadow Home secretary David Davis called the plan "sinister."[44]

Recently, serious concerns about the security implications of using conventional biometric templates in schools have been raised by a number of leading IT security experts, including Kim Cameron, architect of identity and access in the connected systems division at Microsoft, who cites research by Cavoukian and Stoianov[48] to back up his assertion that "it is absolutely premature to begin using 'conventional biometrics' in schools".

Biometric vendors claim benefits to schools such as improved reading skills, decreased wait times in lunch lines and increased revenues.[49] They do not cite independent research to support this. Educationalist Dr Sandra Leaton Gray of Homerton College, Cambridge stated in early 2007 that "I have not been able to find a single piece of published research which suggests that the use of biometrics in schools promotes healthy eating or improves reading skills amongst children... There is absolutely no evidence for such claims".

The Ottawa Police in Canada advised parents who fear that their children may be kidnapped to have their fingerprints taken.[50]

[edit] Other uses

[edit] Locks and other applications

In the 2000s, electronic fingerprint readers have been introduced for security applications such as identification of computer users (log-in authentication). However, early devices have been discovered to be vulnerable to quite simple methods of deception, such as fake fingerprints cast in gels. In 2006, fingerprint sensors gained popularity in the notebook PC market. Built-in sensors in ThinkPads, VAIO laptops, and others also double as motion detectors for document scrolling, like the scroll wheel.

Another recent use of fingerprints in a day-to-day setting has been the increasing reliance on biometrics in schools where fingerprints and, to a lesser extent, iris scans are used to validate electronic registration, cashless catering, and library access. This practice is particularly widespread in the UK, where more than 3500 schools currently use such technology, though it is also starting to be adopted in some states in the US.

[edit] Fingerprints in other species

Some other animals, including many primates, koalas, and fishers have their own unique prints.[51] According to one study, even with an electron microscope, it can be quite difficult to distinguish between the fingerprints of a koala and a human.[52]

[edit] Fingerprinting in fiction

- The 1985 Granada TV adoption of The Adventure of the Final Problem, an 1893 Sherlock Holmes short story set in 1891, has a plot hole in Holmes's use of the Bertillon criminal ID system, in which he uses fingerprints to trap Moriarty's agents and recover the Mona Lisa. The real Bertillon system did not use fingerprints. Bertillon added four spaces for fingerprints on his identification cards by 1900 because of fingerprinting's growing popularity, however the identification cards were still organized based on anthropometric measurements.

- In The Norwood Builder, an 1903 Sherlock Holmes short story set in 1894, the discovery of a bloody fingerprint helps Holmes expose the real criminal and free his client.

[edit] See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Fingerprints |

- International Association for Identification

- Automated fingerprint identification

- Juan Vucetich

- Brain fingerprinting

- Fingerprint Verification Competition

- Government database

- New York State Police Troop C scandal

- Forged evidence

- Fingerprint authentication

- Fingerprint powder

- Naegeli syndrome

- Dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis

- 1,8-Diazafluoren-9-one, chemical used to find fingerprints on porous surfaces

- Dermatoglyphics

[edit] References

- ^ a b Peer Reviewed Glossary of the Scientific Working Group on Friction Ridge Analysis, Study and Technology (SWGFAST)

- ^ "Fake finger reveals the secrets of touch", Nature, 29 January 2009, doi:10.1038/news.2009.68

- ^ Olsen, Robert D., Sr. (1972) “The Chemical Composition of Palmar Sweat”, Fingerprint and Identification Magazine Vol 53(10)

- ^ a b c Ashbaugh, David R. (1991) "Ridgeology". Journal of Forensic Identification Vol 41 (1) ISSN: 0895-l 73X

- ^ a b c Zabell, Sandy "Fingerprint Evidence" Journal of Law and Policy [1]

- ^ Johnson, P. Lee (1973) "Life of Latents" Identification News Vol 23(1)

- ^ a b c Engert, Gerald J. (1964) "International Corner" Identification News Vol 14(1)

- ^ Henry, Edward R., Sir (1900) Classification and Uses of Finger Prints London: George Rutledge & Sons, Ltd.

- ^ Berthold Laufer (1912) “History of the finger-print system,” Smithsonian Institution Annual Report. Available on-line at: http://www.scafo.org/library/160201.html . Reprinted in: The Print [newsletter of South California Association of Fingerprint Officers], vol. 16, no. 2, pages 1- 13. (March/April 2000); available on-line at: http://www.scafo.org/The_Print/THE_PRINT_VOL_16_ISSUE_02.PDF .

- ^ David Ashbaugh, Quantitative-Qualitative Friction Ridge Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Ridgeology (Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1999), pages 11-19.

- ^ Paul Åström (2007) “The study of ancient fingerprints,” Journal of Ancient Fingerprints, no. 1, pages 2-3. Available on-line at: http://www.ancientfingerprints.org/nr1_lo.pdf .

- ^ Paul Åström and Sven A. Eriksson, Fingerprints and Archaeology, vol 28 in the Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology series (Göteborg, Sweden: Paul Åströms Förlag, 1980).

- ^ Joseph Toussaint Reinaud, Relation des voyages faits par les Arabes et les Persans dans l'Inde et a la Chine dans le IX Siecle... (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1845), vol. I, p. 42; quoted in: Laufer (1912).

- ^ Cummins, Harold (1941) “Ancient finger prints in clay,” The Scientific Monthly, vol. 52, pages 389–402. Reprinted in: Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, vol. 34, no. 4, pages 468-481 (November/December 1941).

- ^ Ashbaugh (1999), page 15.

- ^ Ashbaugh (1999), page 17; see also Laufer (1912).

- ^ Simon Cole, Suspect Identities: A history of fingerprinting and criminal identification (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2001), pages 60-61.

- ^ See also an on-line history of fingerprinting: http://www.onin.com/fp/fphistory.html .

- ^ Nehemiah Grew, "The description and use of the pores in the skin of the hands and feet," Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, vol. 14, pages 566-567 (1684).

- ^ Govard Bidloo, Anatomia Humani Corporis [Anatomy of the Human Body](Amsterdam, Netherlands: 1685).

- ^ Marcello Malpighi, De Externo Tactus Organo Anatomica Observatio [Anatomical Observations of the External Organs of Touch](Naples, Italy: Aegidius Longus, 1685).

- ^ Biography of Johann C. A. Mayer (in German): http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Christoph_Andreas_Mayer .

- ^ Johann Christoph Andreas Mayer, Anatomische Kupfertafeln nebst dazu gehorigen Erklarungen [Anatomical Illustrations (etchings) with Accompanying Explanations] (Berlin, Prussia: Georg Jacob Decker, 1783-1788). See especially the 1788 volume.

- ^ Jan Evangelista Purkyně, Commentatio de examine physiologico organi visus et systematis cutanei [Commentary on the physiological examination of the visual organ and the skin system] (Breslau, Prussia: University of Breslau Press, 1823), 58 pages. See also: Harold Cummins and Rebecca Wright Kennedy, "Purkinje's observations (1823) on finger prints and other skin features," The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, vol. 31, no. 3, pages 343-356 (September/October 1940).

- ^ Georg von Meissner, Beiträge zur Anatomie und Physiologie der Haut [Contributions to the Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin] (Leipzig, Saxony: Leopold Voss, 1853).

- ^ William James Herschel, "Skin furrows of the hand," Nature, vol. 23, no. 578, page 76 (25 November 1880). Available on-line at: http://www.eneate.freeserve.co.uk/page4.html .

- ^ Faulds, Henry, MD (1880) "On the skin-furrows of the hand," Nature, vol. 22, no. 574, page 605 (28 October 1880).

- ^ Reid, Donald L. (2003) "Dr. Henry Faulds - Beith Commemorative Society" Journal of Forensic Identification Vol53(2)

- ^ See also this on-line article on Henry Faulds: http://www.galton.org/fingerprints/faulds.htm#herschel1880 .

- ^ Galton, Francis, MD, Sir (1892) Finger Prints London: MacMillan and Co.

- ^ Tewari RK, Ravikumar KV. History and development of forensic science in India. J. Postgrad Med 2000,46:303-308.

- ^ J.S. Sodhi & Jasjeed Kaur. The forgotten Indian pioneers of finger print science, Current Science 2005, 88(1):185-191.

- ^ Specter, Michael "Do Fingerprints Lie" The New Yorker [2]

- ^ International Association for Identification History, retrieved August 2006

- ^ a b Bonebrake, George J. (1978) "Report on the Latent Print Certification Program" Identification News Vol28(3)

- ^ a b c d e f "U.S. Will Pay $2 Million to Lawyer Wrongly Jailed - New York Times" (article), by Eric Lichtbau, New York Times, 2006-11-30, webpage: NYT-061130-settle: on Brandon Mayfield mistaken arrest.

- ^ New York Times; May 31, 2004; Can Prints Lie? Yes, Man Finds To His Dismay. In front of the immigration judge, the tall, muscular man began to weep. No, he had patiently tried to explain, he was not Leo Rosario, a drug dealer and a prime candidate for deportation. He was telling the truth. He was René Ramón Sánchez, an auto-body worker and merengue singer ...

- ^ Abel, David (2007-10-26). "Man wrongly convicted in Boston police shooting found dead". The Boston Globe. http://www.boston.com/news/globe/city_region/breaking_news/2007/10/man_wrongly_con.html.

- ^ Empreintes digitales pour les enfants d'une école de Londres (French)

- ^ Leave Them Kids Alone (English)

- ^ Empreintes digitales pour sécuriser l'école ? (French)

- ^ Le lecteur d'empreintes dans les écoles crée la polémique, 7 Sur 7, February 5, 2007 (French)

- ^ a b Fingerprinting of UK school kids causes outcry, The Register, July 22, 2002 (English)

- ^ a b Child fingerprint plan considered, BBC, March 4, 2007 (English)

- ^ Schools can fingerprint children without parental consent, The Register, September 7, 2006 (English)

- ^ Prises d'empreintes digitales dans un établissement scolaire, Question d'actualité à la Ministre-Présidente en charge de l'Enseignement obligatoire et de Promotion sociale (French)

- ^ Quand la biométrie s'installe dans les cantines au nez et à la barbe de la Cnil, Zdnet, September 9, 2003 (French)

- ^ Biometric Encrypton: A Positive-Sum Technology that Achieves Strong Authentication, Security AND Privacy Cavoukian, A and Stoianov, A March 2007

- ^ Fingerprint Software Eliminates Privacy Concerns and Establishes Success (FindBiometrics)

- ^ Child Print (Ottawa Police Service) (English)/(French)

- ^ http://www.virtualsciencefair.org/2004/fren4j0/public_html/animal_fingerprints.htm

- ^ Henneberg, Maciej; Lambert, Kosette M., Leigh, Chris M. (1997). "Fingerprint homoplasy: koalas and humans". naturalSCIENCE.com 1. http://naturalscience.com/ns/articles/01-04/ns_hll.html.

[edit] External links

[edit] General

- FBI Fingerprint Guide

- FBI Fingerprinting Video Lesson (4-sec Quicktime video of rolling a single inked finger)

- Human Fingerprints at Fingerprinting.com.

- Fingerprint Processing Guide

- Latent Print Examination

[edit] Books, Articles, & Journals

- Galton's Finger Prints

- Henry, Faulds, and Herschel's works on fingerprints

- James C. Cowger, Friction Ridge Skin: Comparison and Identification of Fingerprints (Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1992).

- David R. Ashbaugh, Quantitative-Qualitative Friction Ridge Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Ridgeology (Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 1999).

- Colin Beavan, Fingerprints: The Origins of Crime Detection and the Murder Case that Launched Forensic Science (New York, New York: Hyperion, 2001).

- Surgeon jailed for removing fingerprints - Sydney Morning Herald (news article)

[edit] Biometrics

- FAQ concerning biometrics and fingerprints, TST Biometrics

- Biometrics

- Biometrics Research Lab - Michigan State University

[edit] Errors & Concerns

- How to fake fingerprints

- Will West as fable

- New Yorker: Do fingerprints lie?

- Why Experts Make Errors, Itiel E. Dror, David Charlton, Journal of Forensic Identification

- The use of fingerprints for identification in schools (Leave Them Kids Alone)

[edit] Science & Statistics

- Fingerprint research and evaluation at the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology

- Fingerprint pattern distribution statistics

- Do you have unusual fingerprints?

- The Science of Fingerprints at Project Gutenberg

- FINGERPRINT EVIDENCE Sandy L. Zabell, Ph.D "Journal of Law and Policy"

- All American mom is convicted drug dealer Telegraph.co.uk May 2, 2008

[edit] Commercial Sites & Societies

- The Fingerprint Society - Society for Fingerprint Examiners.

- Scientific Working Group on Friction Ridge Analysis, Study and Technology - U.S. national working group on fingerprint examination.