The Tell-Tale Heart

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Tell-Tale Heart | |

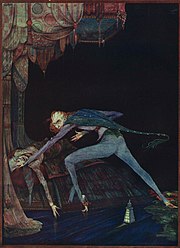

Illustration by Harry Clarke, 1919. |

|

| Author | Edgar Allan Poe |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror Short story |

| Publisher | The Pioneer |

| Publication date | January 1843 |

| Media type | print (periodical) |

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe first published in 1843. It follows an unnamed narrator who insists on his sanity after murdering an old man with a "vulture eye". The murder is carefully calculated, and the murderer hides the body by cutting it into pieces and hiding it under the floorboards. Ultimately the narrator's guilt manifests itself in the hallucination that the man's heart is still beating under the floorboards.

It is unclear what relationship, if any, the old man and his murderer share. It has been suggested that the old man is a father figure, or whether the narrator works for the old man as a servant, perhaps, that his vulture eye represents some sort of veiled secret, or power. The ambiguity and lack of details about the two main characters stand in stark contrast to the specific plot details leading up to the murder.

The story was first published in James Russell Lowell's The Pioneer in January 1843. "The Tell-Tale Heart" is widely considered a classic of the Gothic fiction genre and one of Poe's most famous short stories.

Contents |

[edit] Plot summary

- Note: Due to the ambiguity surrounding the identity of the story's narrator, that character's sex cannot be known for certain. However, for ease of description masculine pronouns are used in this article.

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is a first-person narrative of an unnamed narrator who insists he is sane but suffering from a disease which causes "over-acuteness of the senses." The old man with whom he lives has a clouded, pale, blue "vulture-like" eye which so distresses the narrator that he plots to murder the old man. The narrator insists that his careful precision in committing the murder shows that he cannot possibly be insane. For seven nights, the narrator opens the door of the old man's room, a process which takes him a full hour. However, the old man's vulture eye is always closed, making it impossible to "do the work".

On the eighth night, the old man awakens and sits up in his bed while the narrator performs his nightly ritual. The narrator does not draw back and, after some time, decides to open his lantern. A single ray of light shines out and lands precisely on the old man's eye, revealing that it is wide open. Hearing the old man's heartbeat beating unusually and dangerously quick from terror, the narrator decides to strike, jumping out with a loud yell giving the old man a heart attack and then smothering the old man with his own bed. The narrator proceeds to chop up the body and conceal the pieces under the floorboards. The narrator makes certain to hide all signs of the crime. Even so, the old man's scream during the night causes a neighbor to call the police. The narrator invites the three officers to look around. Claiming that the screams heard were his own in a nightmare, and that the man is out of town at the moment. Confident that they will not find any evidence of the murder, the narrator brings chairs for them and they sit in the old man's room, right on the very spot where the body was concealed, yet they suspect nothing, as the narrator has a pleasant and easy manner about him.

The narrator, however, begins to hear a faint noise. As the noise grows louder, the narrator comes to the conclusion that it is the heartbeat of the old man coming from under the floorboards instead of the possibility that it is his own nervous heartbeat. The sound increases steadily, though the officers seem to pay no attention to it. Shocked by the constant beating of the heart and a feeling that not only are the officers aware of the sound, but that they also suspect him, the narrator confesses to killing the old man and tells them to tear up the floorboards to reveal the body.

[edit] Analysis

"The Tell-Tale Heart" starts in medias res, in the middle of an event. The opening is an in-progress conversation between the narrator and another person who is not identified in any way. It is speculated that the narrator is confessing to a prison warden, judge, newspaper reporter, doctor or psychiatrist.[1] This sparks the narrator's need to explain himself in great detail.[2] What follows is a study of terror but, more specifically, the memory of terror as the narrator is relating events from the past.[3] The first word of the story, "True!", is an admission of his guilt.[1] This introduction also serves to immediately grab the reader's attention and pull him into the story.[4] From there, every word contributes to the purpose of moving the story forward, possibly making "The Tell-Tale Heart" the best example of Poe's theories on a perfect short story.[5]

The story is driven not by the narrator's insistence upon his innocence but by insistence on his sanity. This, however, is self-destructive because in attempting to prove his sanity he fully admits he is guilty of murder.[6] His denial of insanity is based on his systemic actions and precision—a rational explanation for irrational behavior.[2] This rationality, however, is undermined by his lack of motivation ("Object there was none. Passion there was none."). Despite this, he says the idea of murder, "haunted me day and night."[6] The story's final scene, however, is a result of the narrator's feelings of guilt. Like many characters in the Gothic tradition, his nerves dictate his true nature. Despite his best efforts at defending himself, the narrator's "over acuteness of the senses," which help him hear the heart beating in the floorboards, is actually evidence that he is truly mad.[7] Readers during Poe's time would have been especially interested amidst the controversy over the insanity defense in the 1840s.[8]

The narrator claims to have a disease which causes hypersensitivity in his senses. A similar motif is used for Roderick Usher in "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) and in "The Colloquy of Monos and Una" (1841).[9] It is unclear, however, if the narrator actually has very acute senses or if he is merely imagining things. If his condition is believed to be true, what he hears at the end of the story may not be the old man's heart but death watch beetles. The narrator first admits to hearing death watches in the wall after startling the old man from his sleep. According to superstition, death watches are a sign of impending death. One variety of death watch beetles raps its head against surfaces, presumably as part of a mating ritual, while others emit a ticking sound.[9] Henry David Thoreau had suggested in 1838 that the death watch beetles sound similar to a heartbeat.[10] Alternatively, if the heart beating is really a product of the narrator's imagination, it is that uncontrolled imagination that leads to his own destruction.[11]

The relationship between the old man and the narrator is ambiguous, as are their names, their occupations, and where they live. In fact, that ambiguity adds to the tale as an ironic counter to the strict attention to detail in the plot.[12] The narrator may be a servant of the old man's or, as is more often assumed, his son. In that case, the "vulture" eye of the old man is symbolizing parental surveillance and possibly the paternal principles of right and wrong. The murder of the eye, then, is a removal of conscience.[13] The eye may also represent secrecy, again playing on the ambiguous lack of detail about the old man or the narrator. Only when the eye is finally found open on the final night, penetrating the veil of secrecy, that the murder is carried out.[14] Regardless, their relationship is incidental; the focus of the story is the perverse scheme to commit the perfect crime.[15]

Former United States Poet Laureate Richard Wilbur has suggested that the tale is an allegorical representation of Poe's poem "To Science." The poem shows the struggle between imagination and science. In "The Tell-Tale Heart," the old man represents the scientific rational mind while the narrator is the imaginative.[16]

[edit] Publication history

"The Tell-Tale Heart" was first published in the Boston-based magazine The Pioneer in January 1843, edited by James Russell Lowell. Poe was likely paid only $10.[17] Its original publication included an epigraph which quoted Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "A Psalm of Life".[18] The story was slightly revised when republished in the August 23, 1845, edition of the Broadway Journal. This edition omitted Longfellow's poem because, Poe believed, it was plagiarized.[18] "The Tell-Tale Heart" was reprinted several additional times during Poe's lifetime.[19]

[edit] Adaptations

- The earliest acknowledged adaptation of "The Tell-Tale Heart" was in 1928 in a film of the same name directed by Charles Klein and starring Otto Matiesen and Darvas. It stayed faithful to the original tale[20] though future television and film adaptations often expanded the short story to full-length feature films.[21] One version, a 1953 animated film by UPA read by James Mason,[22] is included among the films preserved in the United States National Film Registry. Other versions are greatly expanded from the original work, including a 1960 version, The Tell-Tale Heart, which adds a love triangle to the story.[23]

- The film Nightmares from the Mind of Poe (2006) adapts "The Tell-Tale Heart" along with "The Cask of Amontillado", "The Premature Burial" and "The Raven".

- The Radio Tales series produced the drama The Tell-Tale Heart for National Public Radio. The story was performed by Winifred Phillips along with music composed by her.

[edit] References

- ^ a b Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'", collected in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780521422437, p. 30.

- ^ a b Cleman, John. "Irresistible Impulses: Edgar Allan Poe and the Insanity Defense", collected in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Harold Bloom. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0791061736, p. 70.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0801857309. p. 394

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 101. ISBN 0815410387

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 394. ISBN 0801857309

- ^ a b Robinson, E. Arthur. "Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'" from Twentieth Century Interpretations of Poe's Tales, edited by William L. Howarth. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1971, p. 94.

- ^ Fisher, Benjamin Franklin. "Poe and the Gothic Tradition," from The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521797276, p. 87.

- ^ Cleman, Bloom's BioCritiques, p. 66.

- ^ a b Reilly, John E. "The Lesser Death-Watch and "'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in The American Transcendental Quarterly. Second quarter, 1969.

- ^ Robison, E. Arthur. "Thoreau and the Deathwatch in Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'," collected in Poe Studies, vol. IV, no. 1. June 1971. pp. 14-16

- ^ Eddings, Dennis W. "Theme and Parody in 'The Raven'", collected in Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu, edited by Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1990. ISBN 0961644923, p. 213.

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, p. 32.

- ^ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972. ISBN 0807123218. p. 223.

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, p. 33.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Gerald. Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. Yale University Press, 1987. p. 132. ISBN 0300037732

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, pp. 31-32.

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991. ISBN 0060923318, p. 201.

- ^ a b Moss, Sidney P. Poe's Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969. p. 151

- ^ ""The Tales of Edgar Allan Poe" (index)". eapoe.org. The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. September 30, 2007. http://www.eapoe.org/works/tales/index.htm. Retrieved on 2007-11-05.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001: 234. ISBN 081604161X

- ^ "IMDb Title Search: The Tell-Tale Heart". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/find?s=tt&q=The+Tell-Tale+Heart. Retrieved on 2007-09-01.

- ^ The Tell-Tale Heart (1953/I) at the Internet Movie Database.

- ^ The Tell-Tale Heart (1960) at the Internet Movie Database.

[edit] External links

- "The Poe Museum" - Full text of The Tell-Tale Heart

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" - Full text of the first printing, from the Pioneer, 1843

- Mid-Twentieth century radio adaptations of "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- Analysis of 'The Tell-Tale Heart'

- Illustrated version of "The Tell-Tale Heart" eText

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" James Arnett's contemporary film adaptation playing online

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" study guide and teaching guide - themes, analysis, quotes, teacher resources

|

|||||||||||||||||||||