Freedom of speech

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Freedom |

| Concepts |

|---|

| Freedom by area |

| Freedoms |

|

Assembly |

| Part of a series on |

| Censorship |

|

| By media |

| Banned books Banned films · Re-edited film |

| Methods |

| Book burning · Bleeping Broadcast delay Content-control software Expurgation · Gag order Pixelization · Postal Prior restraint Self-censorship Whitewashing Chilling effect Conspiracy of silence Verbal offence |

| Contexts |

| Corporate · Political Criminal speech · Hate speech |

| By country |

| Censorship Freedom of speech |

Freedom of speech is the freedom to speak freely without censorship or limitation. The synonymous term freedom of expression is sometimes used to denote not only freedom of verbal speech but any act of seeking, receiving and imparting information or ideas, regardless of the medium used. Freedom of speech and freedom of expression are closely related to, yet distinct from, the concept of freedom of thought. In practice, the right to freedom of speech is not absolute in any country and the right is commonly subject to limitations, such as on "hate speech".

The right to freedom of speech is recognized as a human right under Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and recognized in international human rights law in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The ICCPR recognizes the right to freedom of speech as "the right to hold opinions without interference. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression".[1][2] Furthermore freedom of speech is recognized in European, inter-American and African regional human rights law.

Contents |

[edit] The right to freedom of speech and expression

Freedom of speech, or the freedom of expression, is recognized in international and regional human rights law. The right is enshrined in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 13 of the American Convention on Human Rights, Article 9 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, and the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[3]

The freedom of speech can be found in early human rights documents, such as the British Magna Carta (1215) and The Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789), a key document of the French Revolution.[4] Based on John Stuart Mill's arguments, freedom of speech today is understood as a multi-faceted right that includes not only the right to express, or disseminate, information and ideas, but three further distinct aspects:

- The right to seek information and ideas;

- the right to receive information and ideas;

- the right to impart information and ideas.[3]

International, regional and national standards also recognize that freedom of speech, as the freedom of expression, includes any medium, be it orally, in written, in print, through the Internet or through art forms. This means that the protection of freedom of speech as a right includes not only the content, but also the means of expression.[3]

[edit] Relationship to other rights

The right to freedom of speech is closely related to other rights, and may be limited when conflicting with other rights (see Limitations on freedom of speech). The right to freedom of speech is particularly important for media, which plays a special role as the bearer of the general right to freedom of expression for all (see freedom of the press).[3]

[edit] Origins and academic freedom

Freedom of speech and expression has a long history that predates modern international human rights instruments. In Islamic ethics freedom of speech was first declared in the Rashidun period by the caliph Umar in the 7th century.[5] In the Abbasid Caliphate period, freedom of speech was also declared by al-Hashimi (a cousin of Caliph al-Ma'mun) in a letter to one of the religious opponents he was attempting to convert through reason.[6] According to George Makdisi and Hugh Goddard, "the idea of academic freedom" in universities was "modelled on Islamic custom" as practiced in the medieval Madrasah system from the 9th century. Islamic influence was "certainly discernible in the foundation of the first deliberately-planned university" in Europe, the University of Naples Federico II founded by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in 1224.[7]

[edit] Freedom of speech and truth

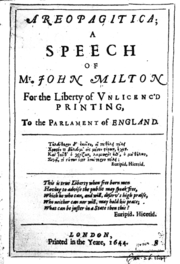

One of the earliest Western defences of freedom of expression is Areopagitica (1644) by the English poet and political writer John Milton. Milton wrote in reaction to an attempt by the English republican parliament to prevent "seditious, unreliable, unreasonable and unlicensed pamphlets". Milton advanced a number of arguments in defence of freedom of speech: a nation's unity is created through blending individual differences rather than imposing homogeneity from above; that the ability to explore the fullest range of ideas on a given issue was essential to any learning process and truth cannot be arrived upon unless all points of view are first considered; and that by considering free thought, censorship acts to the detriment of material progress.

Milton also argued that if the facts are laid bare, truth will defeat falsehood in open competition, but this cannot be left for a single individual to determine. According to Milton, it is up to each individual to uncover their own truth; no one is wise enough to act as a censor for all individuals.[8]

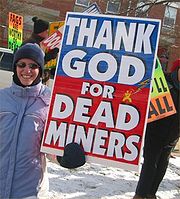

Noam Chomsky states that: "If you believe in freedom of speech, you believe in freedom of speech for views you don't like. Goebbels was in favor of freedom of speech for views he liked. So was Stalin. If you're in favor of freedom of speech, that means you're in favor of freedom of speech precisely for views you despise."[9] An often cited quote that describes the principle of freedom of speech comes from Evelyn Beatrice Hall (often mis-attributed to Voltaire) "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it," as an illustration of Voltaire's beliefs.[10] Professor Lee Bollinger argues that "the free speech principle involves a special act of carving out one area of social interaction for extraordinary self-restraint, the purpose of which is to develop and demonstrate a social capacity to control feelings evoked by a host of social encounters." The free speech principle is left with the concern of nothing less than helping to shape "the intellectual character of the society". According to Bollinger tolerance is a desirable, if not essential, value and protecting unpopular speech is itself an act of tolerance. Such tolerance serves as a model that encourages more tolerance throughout society. However, critics argue that society need not be tolerant of the intolerance of others, such as those who advocate great harm, such as genocide. Preventing such harms is claimed to be much more important than being tolerant of those who argue for them.[11]

[edit] Democracy

One of the most notable proponents of the link between freedom of speech and democracy is Alexander Meiklejohn. He argues that the concept of democracy is that of self-government by the people. For such a system to work an informed electorate is necessary. In order to be appropriately knowledgeable, there must be no constraints on the free flow of information and ideas. According to Meiklejohn, democracy will not be true to its essential ideal if those in power are able to manipulate the electorate by withholding information and stifling criticism. Meiklejohn acknowledges that the desire to manipulate opinion can stem from the motive of seeking to benefit society. However, he argues, choosing manipulation negates, in its means, the democratic ideal.[12] Eric Barendt has called the defence of free speech on the grounds of democracy "probably the most attractive and certainly the most fashionable free speech theory in modern Western democracies".[13]

Thomas I. Emerson expanded on this defence when he argued that freedom of speech helps to provide a good balance between stability and change. Freedom of speech acts as a "safety valve" to let off steam when people might otherwise be bent on revolution. He argues that "The principle of open discussion is a method of achieving a moral adaptable and at the same time more stable community, of maintaining the precarious balance between healthy cleavage and necessary consensus." Emerson furthermore maintains that "Opposition serves a vital social function in offsetting or ameliorating (the) normal process of bureaucratic decay."[14] Research undertaken by the Worldwide Governance Indicators project at the World Bank, indicates that freedom of speech, and the process of accountability that follows it, have a significant impact in the quality of governance of a country. "Voice and Accountability" within a country, defined as "the extent to which a country's citizens are able to participate in selecting their government, as well as freedom of expression, freedom of association, and free media" is one of the six dimensions of governance that the Worldwide Governance Indicators measure for more than 200 countries.[15]

[edit] Social interaction and community

Richard Moon has developed the argument that the value of freedom of speech and freedom of expression lies with social interactions. Moon writes that "by communicating an individual forms relationships and associations with others - family, friends, co-workers, church congregation, and countrymen. By entering into discussion with others an individual participates in the development of knowledge and in the direction of the community."[16]

[edit] Limitations on freedom of speech

- For specific country examples see Freedom of speech by country, and Criminal speech.

According to the Freedom Forum Organization, legal systems, and society at large, recognize limits on the freedom of speech, particularly when freedom of speech conflicts with other values or rights.[18] Exercising freedom of speech always takes place within a context of competing values. Limitations to freedom of speech may follow the "harm principle" or the "offense principle", for example in the case of pornography or "hate speech".[19] Limitations to freedom of speech may occur through legal sanction and/or social disapprobation.[20]

In "On Liberty" (1859) John Stuart Mill argued that "...there ought to exist the fullest liberty of professing and discussing, as a matter of ethical conviction, any doctrine, however immoral it may be considered."[20] Mill argues that the fullest liberty of expression is required to push arguments to their logical limits, rather than the limits of social embarrassment. However, Mill also introduced what is known as the harm principle, in placing the following limitation on free expression: "the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.[20]

In 1985 Joel Feinberg introduced what is known as the "offence principle", arguing that Mill's harm principle does not provide sufficient protection against the wrongful behaviours of others. Feinberg wrote "It is always a good reason in support of a proposed criminal prohibition that it would probably be an effective way of preventing serious offense (as opposed to injury or harm) to persons other than the actor, and that it is probably a necessary means to that end."[22] Hence Feinberg argues that the harm principle sets the bar too high and that some forms of expression can be legitimately prohibited by law because they are very offensive. But, as offending someone is less serious than harming someone, the penalties imposed should be higher for causing harm.[22] In contrast Mill does not support legal penalties unless they are based on the harm principle.[20] Because the degree to which people may take offense varies, or may be the result of unjustified prejudice, Feinberg suggests that a number of factors need to be taken into account when applying the offense principle, including: the extent, duration and social value of the speech, the ease with which it can be avoided, the motives of the speaker, the number of people offended, the intensity of the offense, and the general interest of the community at large.[20]

[edit] The Internet

International, national and regional standards recognise that freedom of speech, as one form of freedom of expression, applies to any medium, including the Internet.[3]

[edit] Freedom of information

Jo Glanville, editor of the Index on Censorship, states that "the Internet has been a revolution for censorship as much as for free speech". [23] Freedom of information is an extension of freedom of speech where the medium of expression is the Internet. Freedom of information may also refer to the right to privacy in the context of the Internet and information technology. As with the right to freedom of expression, the right to privacy is a recognised human right and freedom of information acts as an extension to this right.[24] Freedom of information may also concern censorship in an information technology context, i.e. the ability to access Web content, without censorship or restrictions.[citation needed]

The World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) Declaration of Principles adopted in 2003 reaffirms democracy and the universality, indivisibility and interdependence of all human rights and fundamental freedoms. The Declaration also makes specific reference to the importance of the right to freedom of expression for the "Information Society" in stating:

"We reaffirm, as an essential foundation of the Information Society, and as outlined in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, that everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; that this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers. Communication is a fundamental social process, a basic human need and the foundation of all social organisation. It is central to the Information Society. Everyone, everywhere should have the opportunity to participate and no one should be excluded from the benefits of the Information Society offers."[25]

The Internet opens new possibilities for exercising freedom of speech. The pseudonymity of the Internet allows people to communicate. Data havens (such as Freenet) and gripe sites allow free speech by guaranteeing that material cannot be removed (censored).[citation needed]

[edit] Internet censorship

The concept of freedom of information has emerged in response to state sponsored censorship, monitoring and surveillance of the internet. Internet censorship includes the control or suppression of the publishing or accessing of information on the Internet.[citation needed] The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) is an organization dedicated to protecting freedom of speech on the Internet. The Open Net Initiative (ONI) is a collaboration between the Citizen Lab at the Munk Centre for International Studies, the University of Toronto, the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard Law School, the Advanced Network Research Group at the Cambridge Security Programme (University of Cambridge), and the Oxford Internet Institute, at Oxford University which aims to investigate, expose, and analyze Internet filtering and surveillance practices in a credible and non-partisan fashion.[citation needed] Groups such as the Global Internet Freedom Consortium advocate for freedom of information for what they term "closed societies".[26]

According to the Reporters without Borders (RSF) "internet enemy list" the following states engage in pervasive internet censorship: Cuba, Iran, Maldives, Myanmar/Burma, North Korea, Syria, Tunisia, Uzbekistan and Vietnam.[27]

A widely publicised example is the "Great Firewall of China" (in reference both to its role as a network firewall and to the ancient Great Wall of China). The system blocks content by preventing IP addresses from being routed through and consists of standard firewall and proxy servers at the Internet gateways. The system also selectively engages in DNS poisoning when particular sites are requested. The government does not appear to be systematically examining Internet content, as this appears to be technically impractical.[28] Internet censorship in the People's Republic of China is conducted under a wide variety of laws and administrative regulations. In accordance with these laws, more than sixty Internet regulations have been made by the People's Republic of China (PRC) government, and censorship systems are vigorously implemented by provincial branches of state-owned ISPs, business companies, and organizations.[29][30]

[edit] See also

- Clear and present danger

- Copyleft

- Copyright

- Digital rights

- Fairness Doctrine

- Fighting words

- Fleeting expletive

- Free content

- Freedom of the press

- Gripe site

- Heckler's veto

- Imminent lawless action

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- Kincaid v. Gibson

- Media transparency

- OAS Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression

- Parrhesia

- Verbal offence

[edit] References

- ^ OHCHR

- ^ Using Courts to Enforce the Free Speech Provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | Australia & Oceania > Australia & New Zealand from All Business...

- ^ a b c d e Andrew Puddephatt, Freedom of Expression, The essentials of Human Rights, Hodder Arnold, 2005, pg.128

- ^ http://www.guardian.co.uk/media/2006/feb/05/religion.news

- ^ Boisard, Marcel A. (July 1980), "On the Probable Influence of Islam on Western Public and International Law", International Journal of Middle East Studies 11 (4): 429–50

- ^ Ahmad, I. A. (June 3, 2002), "The Rise and Fall of Islamic Science: The Calendar as a Case Study" (PDF), “Faith and Reason: Convergence and Complementarity”, Al-Akhawayn University, http://images.agustianwar.multiply.com/attachment/0/RxbYbQoKCr4AAD@kzFY1/IslamicCalendar-A-Case-Study.pdf, retrieved on 2008-01-31

- ^ Goddard, Hugh (2000), A History of Christian-Muslim Relations, Edinburgh University Press, p. 100, ISBN 074861009X

- ^ Andrew Puddephatt, Freedom of Expression, The essentials of Human Rights, Hodder Arnold, 2005, pg.127

- ^ Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, 1992

- ^ Boller, Jr., Paul F.; George, John (1989). They Never Said It: A Book of Fake Quotes, Misquotes, and Misleading Attributions. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 0-19-505541-1.

- ^ Lee Bollinger, The Tolerant Society, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1988

- ^ Marlin, Randal (2002). Propaganda and the Ethics of Persuasion. Broadview Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 1551113767 978-1551113760. http://books.google.com/books?id=Zp38Ot2g7LEC&pg=PA226&dq=%22free+speech%22+democracy&lr=#PPA229,M1.

- ^ Marlin, Randal (2002). Propaganda and the Ethics of Persuasion. Broadview Press. p. 226. ISBN 1551113767 978-1551113760. http://books.google.com/books?id=Zp38Ot2g7LEC&pg=PA226&dq=%22free+speech%22+democracy&lr=#PPA229,M1.

- ^ Marlin, Randal (2002). Propaganda and the Ethics of Persuasion. Broadview Press. pp. 228–229. ISBN 1551113767 978-1551113760. http://books.google.com/books?id=Zp38Ot2g7LEC&pg=PA226&dq=%22free+speech%22+democracy&lr=#PPA229,M1.

- ^ http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi2007/pdf/booklet_decade_of_measuring_governance.pdf A Decade of Measuring the Quality of Governance

- ^ Marlin, Randal (2002). Propaganda and the Ethics of Persuasion. Broadview Press. p. 229. ISBN 1551113767 978-1551113760. http://books.google.com/books?id=Zp38Ot2g7LEC&pg=PA226&dq=%22free+speech%22+democracy&lr=#PPA229,M1.

- ^ Lundqvist, J.. "More pictures of Iranian Censorship". http://jturn.qem.se/2006/more-pictures-of-iranian-censorship/. Retrieved on August 2007-01-21.

- ^ When May Speech Be Limited?

- ^ Freedom of Speech (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ^ a b c d e Freedom of Speech

- ^ Church members enter Canada, aiming to picket bus victim's funeral

- ^ a b Philosophy of Law

- ^ Glanville, Jo (17 November 2008). "The big business of net censorship". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/nov/17/censorship-internet.

- ^ Protecting Free Expression Online with Freenet - Internet Computing, IEEE

- ^ Klang, Mathias; Murray, Andrew (2005). "Human Rights in the Digital Age". Routledge. 1. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=USksfqPjwhUC&dq=%22digital+rights%22+human+rights&source=gbs_summary_s&cad=0.

- ^ "Mission". Global Internet Freedom Consortium. http://www.internetfreedom.org/mission. Retrieved on 2008-07-29.

- ^ List of the 13 Internet enemies RSF, 2006 November

- ^ "War of the words". The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/china/story/0,,1713317,00.html.

- ^ "II. How Censorship Works in China: A Brief Overview". Human Rights Watch. http://www.hrw.org/reports/2006/china0806/3.htm. Retrieved on 2006-08-30.

- ^ Chinese Laws and Regulations Regarding Internet

[edit] Further reading

- Sunstein, Cass (1995). "Democracy and the problem of free speech". Publishing Research Quarterly 11 (4): 58–72. doi:.

- Callamard, Agnes; ARTICLE 19 (2008). Speaking Out for Free Expression: 1987-2007 and Beyond.

- Schweigl, Johan (2008). "Limits of Freedom of Expression- when it comes to flag burning" (PDF). in: A Brief Introduction to Czech Law. Rincon: The American Institute for Central European Legal Studies (AICELS): 76-89. http://www.aicels.org/aicels/Interduction_to_czech_law_-_AICELS%20-%20Abstract1.pdf.

[edit] External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Freedom of speech |

- Speaking Out for Free Expression: 1987-2007 and Beyond

- Timeline: a history of free speech

- UN-Resolution 217 A III - (Meinungsfreiheit.org)

- ARTICLE 19, Global Campaign for Free Expression

- The journalist fired for calling Bush a coward after 9/11

- Banned Magazine, the journal of censorship and secrecy.

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange

- irrepressible.info - Amnesty International's campaign against internet repression

- Organization of American States - Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression

- Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe - Representative on Freedom of the Media

- African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights - Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression in Africa

- UNESCO - Programme on Freedom of Expression

- FREEMUSE - Freedom of Musical Expression

- Ringmar, Erik A Blogger's Manifesto: Free Speech and Censorship in the Age of the Internet (London: Anthem Press, 2007)

- The BOBs - weblog award promoting freedom of speech

- UN undermines freedom of expression, rapporteur to nail anti-Islamic speech

- The Expressionist: India's track record

- Worldwide Governance Indicators Worldwide ratings of country performances on Voice and Accountability and other governance dimensions from 1996 to present.

- Free Speech Links - weblog linked to A Very Short Introduction to Free Speech

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||