Jolly Roger

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Jolly Roger is the name given to any of various flags flown to identify a ship's crew as pirates.[1] The flag most usually identified as the Jolly Roger today is the skull and crossbones, being a flag consisting of a skull above two long bones set in an x-mark arrangement on a black field. This design was used by four pirates, captains Edward England, John Taylor, Sam Bellamy and John Martel.[citation needed] Despite its prominence in popular culture, plain black flags were often employed by most pirates in the 17th-18th century. [2] Historically, the flag was flown to frighten pirates' victims into surrendering without a fight, since it conveyed the message that the attackers were outlaws who would not consider themselves bound by the usual rules of engagement -- and might, therefore, slaughter those they defeated. (Since captured pirates were usually hanged, they didn't have much to gain by asking quarter if defeated.) The same message was sometimes conveyed by a red flag, as discussed below.

Since the decline of piracy, various military units have used the Jolly Roger, usually in skull-and-crossbones design, as a unit identification insignia or a victory flag to ascribe to themselves the proverbial ferocity and toughness of pirates. It has also unofficially been used to signify Electric Hazard and Poisons. The background is blood red and the Skull and Bones are black in colour.

Contents |

[edit] Origins of the term

The name "Jolly Roger" goes back at least to Charles Johnson's A General History of the Pyrates, published in 1724. Johnson specifically cites two pirates as having named their flag "Jolly Roger": Bartholomew Roberts in June, 1721[3] and Francis Spriggs in July, 1723. While Spriggs and Roberts used the same name for their flags, their flag designs were quite different, suggesting that already "Jolly Roger" was a generic term for black pirate flags rather than a name for any single specific design. Neither Spriggs' nor Roberts' Jolly Roger consisted of a skull and crossbones.

Richard Hawkins, captured by pirates in 1724, reported that the pirates had a black flag bearing the figure of a skeleton stabbing a heart with a spear, which they named "Jolly Roger". [4]

Despite this tale, it is assumed by most that the name Jolly Roger comes from the French words jolie rouge, meaning "pretty red".[5][6] Supporting this theory is that during the Elizabethan era "Roger", which was derived from the French "rouge", was a slang term for beggars and vagrants who "pretended scholarship"[7] and was also applied to privateers who operated in the English Channel. "Sea Beggars" had been a popular name for Dutch privateers since the 16th century.[8] Another theory states that "Jolly Roger" is an English corruption of "Ali Raja", the name of a Tamil pirate.[5][9] Yet another theory is that it was taken from a nickname for the devil, "Old Roger".[9] The "jolly" appellation may be derived from the apparent grin of a skull. Theories that the epithet comes from the names of various pirates, such as Woodes Rogers, are generally discredited.[citation needed]

In his book Pirates & The Lost Templar Fleet, David Hatcher Childress claims that the flag was named after the first man to fly it, King Roger II of Sicily (c.1095-1154). Roger was a famed Templar and the Knights Of The Temple were in conflict with the Pope over his conquests of Apulia and Salerno in 1127.[10] Childress claims that, many years later, after the Templars were disbanded by the church, at least one Templar fleet split into four independent flotillas dedicating themselves to pirating ships of any country sympathetic to Rome, thus the flag was an inheritance, and its crossed bones a reference to the original Templar logo of a red cross with blunted ends.

[edit] Origins of the design

While privateers are shown in earlier Dutch paintings flying a red flag, the first written record of what it was used for occurred in 1694 when an English Admiralty law made the flying of a red flag, known as a "Red Jack", mandatory to distinguish them from Navy ships. The first references to a black flag are contained in records of privateering actions dated 1697. These records show that when the victim's vessel showed resistance, the Red Jack was lowered and a black flag raised in its place to indicate no quarter would be given. A yellow flag was also used but there is no record of its meaning. With the end of the War of the Spanish Succession in 1714, many of the privateers turned to piracy and continued to use the red and black flags but now decorated with their own designs. Edward England, for example, flew the black flag depicted above from his mainmast, a red version of the same flag from his foremast, and the English National flag from his ensign staff.[8]

The first record of the skull and crossed bones design being used by pirates is an entry in a log book held by the Bibliothèque nationale de France. Dated December 6th, 1687 it describes its use by pirates not on a ship but on land.[11]

"And we put down our white flag, and raised a red flag with a Skull head on it and two crossed bones (all in white and in the middle of the flag), and then we marched on."

Black flags are known to have been used by pirates at least five years before the earliest known attachment of the name "Jolly Roger" to such flags. Contemporary accounts show Captain Martel's pirates using a black flag in 1716,[12] Edward Teach, Charles Vane, and Richard Worley in 1718[13], and Howell Davis in 1719.[14] An even earlier use of a black flag with skull, crossbones, and hourglass is attributed in 1700 to pirate captain Emanuel Wynn, according to a wide variety of secondary sources.[15] Reportedly, these secondary sources are based on the account of Captain John Cranby of the HMS Poole and are verified at the London Public Record Office.

[edit] Jolly Rogers Gallery

|

A Pirate flag often called the "Jolly Roger." This flag is attributed to Blackbeard. |

The pirate flag used by Edward Low |

||

|

Walter Kennedy (pirate)'s Jolly Roger (which was identical to the flag of Jean Thomas Dulaien). |

Traditional depiction of Stede Bonnet's flag. |

Flag of pirate Christopher Condent. |

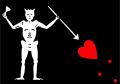

Edward England's Flag |

|

Popular version of Henry Every's Jolly Roger. Reportably also flew a version with a black background |

Jolly Roger flown by Calico Jack Rackham |

Possible flag of Thomas Tew |

|

|

Emanuel Wynn's flag |

[edit] Use in practice

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2007) |

Pirates did not fly the Jolly Roger at all times. Like other vessels, pirate ships usually stocked a variety of different flags, and would normally fly false colors or no colors until they had their prey within firing range.[16] When the pirates' intended victim was within range, the Jolly Roger would be raised, often simultaneously with a warning shot.

The flag was probably intended as communication of the pirates' identity, which may have given target ships an opportunity to change their mind and surrender without a fight. For example in June 1720 when Bartholomew Roberts sailed into the harbour at Trepassey, Newfoundland with black flags flying, the crews of all 22 vessels in the harbour abandoned them in panic.[17] If a ship then decided to resist, the Jolly Roger was taken down and a red flag was flown, indicating that the pirates intend to take the ship by force and without mercy. Richard Hawkins reports that "When they fight under Jolly Roger, they give quarter, which they do not when they fight under the red or bloody flag."[citation needed]

In this view of models, it was important for a prey ship to know that its assailant was a pirate, and not a privateer or government vessel - as the latter two generally had to abide by a rule that a crew that resisted, but then surrendered, could not be executed:

"An angry pirate therefore posed a greater danger to merchant ships than an angry Spanish coast guard or privateer vessel. Because of this, although, like pirate ships, Spanish coast guard vessels and privateers were almost always stronger than the merchant ships they attacked, merchant ships may have been more willing to attempt resisting these "legitimate" attackers than their piratical counterparts. To achieve their goal of taking prizes without a costly fight, it was therefore important for pirates to distinguish themselves from these other ships also taking prizes on the seas."[18]

Flying a Jolly Roger was a reliable way of proving oneself a pirate, as just possessing or using a Jolly Roger was considered proof that one was a criminal pirate (and not something more legitimate); only a pirate would dare fly the Jolly Roger, as they were already under threat of execution.[19]

[edit] Use by submarines

Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson VC, the Controller of the Royal Navy, summed up the opinion of the many in the Admiralty at the time when in 1901 he said submarines were "underhand, unfair, and damned un-English. ... treat all submarines as pirates in wartime ... and hang all crews."[20][21] In response, Lieutenant Commander (later Admiral Sir) Max Horton first flew the Jolly Roger on return to port after sinking the German cruiser SMS Hela and the destroyer SMS S-116 in 1914 while in command of the E class submarine HMS E9.[22][23]

During World War I, the submarine service came of age, receiving five of the Royal Navy's fourteen Victoria Crosses, the first by Lieutenant Norman Holbrook, Commanding Officer of HMS B11.

In World War II it became common practice for the submarines of the Royal Navy and Royal Australian Navy to fly the Jolly Roger on completion of a successful combat mission where some action had taken place, but as an indicator of bravado and stealth rather than of lawlessness. The Jolly Roger is now the emblem of the Royal Navy Submarine Service.[24]

The Jolly Roger was brought to the attention of a post World War II public when HMS Conqueror flew the Jolly Roger on her return from the Falklands War having sunk the cruiser ARA General Belgrano. In May 1991 Oberon class submarines HMS Opossum and her sister HMS Otus returned to the submarine base HMS Dolphin in Gosport from patrol in the Persian Gulf flying Jolly Rogers, for their part in Operation Granby during the Gulf War in 1991.[25][26][27] In 1999 HMS Splendid participated in the Kosovo Conflict and became the first Royal Navy submarine to fire a cruise missile in anger. On her return to Faslane, on July 9, 1999, Splendid flew the Jolly Roger.[28][29]

After Operation Veritas, the attack on Al-Qaeda and Taliban forces following the 9/11 attacks in the United States, HMS Trafalgar entered Plymouth Sound flying the Jolly Roger on March 1, 2002. She was welcomed back by Admiral Sir Alan West, Commander-in-Chief of the fleet and it emerged she was the first Royal Navy submarine to launch tomahawk cruise missiles against Afghanistan.[30] HMS Triumph was also involved in the initial strikes and on returning to port displayed a Jolly Roger emblazoned with two crossed Tomahawks to indicate her opening missiles salvoes in the "war against terrorism".

More recently, on April 16, 2003, HMS Turbulent, the first Royal Navy vessel to return home from the war against Iraq, arrived in Plymouth flying the Jolly Roger after launching thirty Tomahawk cruise missiles.[31]

[edit] United States Military Aviation

Four squadrons of the 90th Bombardment Group of the Fifth Air Force under General George C. Kenney, commanded by Colonel Art Rogers were known as the Jolly Rogers. Easily distinguished by the white skull and crossed bombs, from 1943, the four squadrons all displayed the insignia on the twin tail fins of their B-24 heavy bombers (heavies) with different color backgrounds for each squadron. The 319th's tail fin background was blue, the 320th's red, the 321st, green, and the 400th, the most graphic of the four, black.[32]

Several Naval squadrons have used the Jolly Roger insignia, VF-17/VF-5B/VF-61, VF-84 and VFA-103

[edit] Usage by the pirate movement

The The Pirate Party used the Jolly Rogers as its symbol, before changing to a stylised 'P'. The symbol is still used extensivly in the Pirate movement. The pirate bay sometimes use the symbol alsp.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition 1989, under "Roger, n.2.4" records the first usage as: "1785 GROSE Dict. Vulgar T. s.v. Roger, Jolly roger, a flag hoisted by pirates."

- ^ Regular black flags mostly employed by pirates

- ^ Charles Johnson (1724), A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, CHAP. IX. OF Captain Bartho. Roberts, And his Crew. a copy on the website of Brian Carnell

- ^ David Cordingly (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates, New York: Random House, p. 117.

- ^ a b Jolie Rouge as origin of term jolly roger

- ^ origin of jolly roger term

- ^ http://www.personal.utulsa.edu/~marc-carlson/history/elizlng.html

- ^ a b Cargil-Kipar, Nicole. "Historical Pirate Flags". Late 17th Century Clothing History. http://www.kipar.org/piratical-resources/pirate-flags.html. Retrieved on 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b David Cordingly (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates, New York: Random House, p. 118.

- ^ Stephen Dafoe. The Knights Templar, www.templarhistory.com. Accessed 30 December 2007

- ^ Pirate Flags Pirate Mythtory

- ^ Johnson, p. 66.

- ^ Johnson, p. 72, 147, 344.

- ^ Johnson, p. 187

- ^ See, e.g., Angus Konstam, Pirates: 1660-1730; Douglas Botting, The Pirates; http://www.bonaventure.org.uk/ed/flags.htm; etcetera.

- ^ This practice is considered deceitful today, but in the period of sail it was the standard practice for all ships. There was no other way to approach an enemy or victim on the open sea if they didn't want to fight.

- ^ Burl, Aubery Black Bart pp. 133-4

- ^ pg 10, "Pirational Choice: The Economics of Infamous Pirate Practices", Peter T. Leeson

- ^ "Ships attacking under the death head's toothy grin were therefore considered criminal and could be prosecuted as pirates. Since pirates were criminals anyway, for them, flying the Jolly Roger was costless. If they were captured and found guilty, the penalty they faced was the same whether they used the Jolly Roger in taking merchant ships or not – the hangman's noose... For legitimate ships, however, things were different. To retain at least a veneer of legitimacy, privateers and Spanish coast guard ships could not sail under pirate colors. If they did, they could be hunted and hanged as pirates." pg 12, Leeson 2008.

- ^ "underhand, unfair, and damned un-English."(Stephen Wentworth Roskill (1968). Naval Policy Between the Wars, Walker, ISBN 0870218484 p. 231. cites A. J. Marder, Fear God and Dread Nought, vol. I (Oxford UP, 1961), p.333 and also Williams Jameson, The Most Formidable Thing (Hart-Davis, 1965) pp. 75-76.)

- ^ "underhand, ... and damned Un-English. ... treat all submarines as pirates in wartime ... and hang all crews." (J. R. Hill (1989). Arms Control at Sea, Routledge, ISBN 0415012805. p.35 cites Marder, From the Dreadnoughts to Scapa Flow p.332)

- ^ Staff, The Jolly Roger on a webpage of the National Museum of the Royal Navy

- ^ HMS Triumph and HMS Superb

- ^ General information on the Royal Navy Submarine Service use and history of the Jolly Roger

- ^ Hansard 13 May 1991

- ^ Ian W Hillbeck. Newsletter: Issue 24, Submariners Association Barrow-in-Furness Branch

- ^ Ian W Hillbeck. Submarine Camouflage Schemes, Submariners Association Barrow-in-Furness

- ^ Barton Gellman U.S., NATO Launch Attacks on Yugoslavia Washington Post 25 March 1999

- ^ Swiftsure Class Nuclear Fleet Submarines

- ^ Trafalgar Returns March 1, 2002

- ^ Cruise missile sub (HMS Turbulent) back in UK by Richard Norton-Taylor in The Guardian April 17, 2003

- ^ * Birdsall, Steve. Flying Buccaneers. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, 1977. ISBN 0385032188

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||