Dextroamphetamine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references (ideally, using inline citations). Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2009) |

|

|

|

|

|

Dextroamphetamine

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

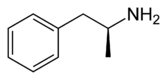

| (2S)-1-phenylpropan-2-amine | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 51-63-8 (sulfate), 1462-73-3 (hydrochloride) |

| ATC code | N06 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C9H13N |

| Mol. mass | 135.2062 |

| SMILES | & |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | oral >75% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Half life | 10–28 hours (Average ~12 hours) |

| Excretion | Renal: ~45% |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | |

| Legal status |

Controlled (S8)(AU) Schedule III(CA) Class B(UK) Schedule II(US) |

| Routes | Clinical: Oral, intravenous, sublingual Recreational: Vaporized, insufflated, suppository |

Dextroamphetamine is a psychostimulant drug which is known to produce increased wakefulness and focus in association with decreased fatigue and appetite. Drugs with similar psychoactive properties are often referred to or described as "amphetamine analogues", "amphetamine-like", or having "amphetaminergic" effects. Enantiomerically pure dextroamphetamine is more powerful than racemic amphetamine and has stimulant properties similar to methamphetamine, but is slightly less potent and far less neuorotoxic.[citation needed]

Dextroamphetamine is the dextrorotary or "Right-handed" stereoisomer of the amphetamine molecule. The amphetamine molecule has 2 stereoisomers: levo-amphetamine "left-handed" & dextro-amphetamine "right-handed" . Common names for dextroamphetamine include d-amphetamine, dexamphetamine, (S)-(+)-amphetamine, and brand names such as Dexedrine and Dextrostat. It makes up approximately 72% of the ADHD drug Adderall and is the active metabolite of the recently introduced 'prodrug' lisdexamfetamine, known by its brand name Vyvanse. In addition, it is an active metabolite of several older N-substituted amphetamine prodrugs used as anorexics, such as clobenzorex (Asenlix), benzphetamine (Didrex) and amphetaminil (Aponeuron).[citation needed]

Contents |

[edit] History

Amphetamine was first synthesized under the chemical name "phenylisopropylamine" in Berlin, 1887 by the Romanian chemist Lazar Edeleanu. It was not widely marketed until 1932, when the pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline, and French (currently known as GlaxoSmithKline) introduced it in the form of the Benzedrine Inhaler, for combating cold symptoms. Notably, the chemical form of Benzedrine in the inhaler was the liquid free-base, not a chloride or sulfate salt. In free-base form, amphetamine is a volatile oil, hence the efficacy of the inhalers.[citation needed]

Three years later, in 1935, the medical community became aware of the stimulant properties of amphetamine, specifically dextroamphetamine, and in 1937 Smith, Kline, and French introduced tablets, under the tradename Dexedrine. In the United States, Dexedrine tablets were approved to treat narcolepsy, attention disorders, depression, and obesity. Dextroamphetamine was marketed in various other forms in the following decades, primarily by Smith, Kline, and French, such as several combination medications including a mixture of dextroamphetamine and amobarbital (a barbiturate) sold under the tradename Dexamyl and, in the 1950s, an extended release capsule (the "Spansule").[citation needed]

It quickly became apparent that Dexedrine and other amphetamines had a high potential for abuse, although they were not heavily controlled until 1970, when the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act was passed by the United States Congress. Dexedrine, along with other sympathomimetics, was eventually classified as schedule II, the most restrictive category possible for a drug with recognized medical uses.[citation needed]

Internationally, it has been available under the names AmfeDyn (Italy), Curban (US), Obetrol (Switzerland), Simpamina (Italy), Dexedrine (US), Dextropa (Portugal), and Stild (Spain). [1]

[edit] Contraindications

Dextroamphetamine treatment alongside MAO inhibitors is strongly contraindicated. Treatment should also be avoided in patients suffering from physical health conditions including cardiovascular diseases, hypertensive disease, hyperthyroidism, glaucoma and anorexia.[citation needed]

Treating patients with a substantial history of drug use for recreational or other non-medicinal purposes is strongly inadvisable. However, it has been reported that people with undiagnosed adult ADD may actually abstain from further recreational drug use, as they[who?] may have been self-medicating in order to control their undiagnosed ADD.[2]

[edit] Effects

Dextroamphetamine, either for recreational or medicinal use, can induce the effects shown below. In general, adverse effects and their severity are relative to the dosage. Standard therapeutic dosages have relatively few serious adverse effects, unless dextroamphetamine is contraindicated with a pre-existing health condition or drug such as an MAO inhibitor.[citation needed]

[edit] Physical effects

Physical effects of dextroamphetamine can include a reduced appetite, anorexia, hyperactivity, dilated pupils, flushing, restlessness, dry mouth, headache, tachycardia, bradycardia, tachypnea, hypertension, hypotension, fever, diaphoresis, diarrhea, constipation, blurred vision, aphasia, dizziness, twitches, insomnia, numbness, palpitations, arrhythmias, tremors, dry and/or itchy skin, acne, pallor and (typically in high doses combined with other drugs and/or pre-existing health conditions) convulsions, coma, heart attack and death.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

[edit] Psychological effects

Psychological effects of dextroamphetamine can include euphoria (via increased dopamine and serotonin), anxiety (via increased norepinephrine), altered libido, increased self-awareness, increased alertness, increased concentration, increased energy, increased self-esteem, increased self-confidence, increased excitation, increased orgasmic intensity, increased sociability, increased irritability, increased aggression, psychomotor agitation, hubris, excessive feelings of power and/or superiority, repetitive and/or obsessive behaviors, paranoia and with high and/or chronic doses amphetamine psychosis can occur.[3][9][10][11]

[edit] Withdrawal effects

Withdrawal symptoms from dextroamphetamine primarily consist of mental fatigue, mental depression and an increased appetite. Symptoms may last for days with occasional abuse and weeks or months with chronic use with severity dependent on the length of time and the amount of dextroamphetamine taken. Withdrawal symptoms may also include anxiety, agitation, excessive sleep, vivid or lucid dreams (deep REM sleep), suicidal thoughts and psychosis. [12][13][14]

[edit] Overdose

The Physician's 1991 Drug Handbook reports: "Symptoms of overdose include restlessness, tremor, hyperreflexia, tachypnea, confusion, aggressiveness, hallucinations, and panic." Dilated pupils are common with high doses.

The fatal dose in humans is not precisely known, but in various species of rat generally ranges between 50 and 100 mg/kg, or a factor of 100 over what is required to produce noticeable psychological effects.[15][16] Although the symptoms seen in a fatal overdose are similar to those of methamphetamine, their mechanisms are not identical, as some substances which inhibit d-amphetamine toxicity do not do so for methamphetamine.[17][18] Methamphetamine is often considered to be significantly more neurotoxic than d-amphetamine in cases of overdose, particularly to serotonergic and dopaminergic neurons in the CNS.[citation needed]

An extreme symptom of overdose is amphetamine psychosis, characterized by vivid visual, auditory, and sometimes tactile hallucinations. Many of its symptoms are identical to the psychosis-like state which follows long-term sleep deprivation, so it remains unclear whether these are solely the effect of the drug, or due to the long periods of sleep deprivation which are often undergone by the chronic user or abuser. "In extraordinarily sensitive individuals--such as those with a pre-existing neuropsychiatric disorder--psychosis may be produced by 55 to 75 mg of dextroamphetamine. With high enough doses, psychosis can probably be induced in anyone." Amphetamine psychosis, however, is extremely rare in individuals taking oral amphetamines at therapeutic doses; it is usually seen in cases of prolonged or high-dose intravenous (IV) for non-medicinal uses.[19]

[edit] Chemistry

Dextroamphetamine is a slightly polar, weak base, and is lipophilic.[citation needed]

[edit] Formulations

[edit] Dextro-amphetamine sulfate

A tablet preparation of the salt d-amphetamine sulfate (pharmaceutical names: Dexedrine or Dextrostat) is available in 5 mg and 10 mg strengths in the United States. A pharmaceutical with a strength of 10 mg d-amphetamine sulfate is 7.28 mg d-amphetamine base. D-amphetamine sulfate is also available in a controlled release version (pharmaceutical name: Dexedrine SR or Dexedrine Spansule), capsulated in the strengths: 5 mg, 10 mg, and 15 mg.

[edit] L-lysine-d-amphetamine

Dextro-amphetamine is also the active metabolite of the prodrug lisdexamfetamine (L-lysine-d-amphetamine) dimesylate (pharmaceutical trade name: Vyvanse). Vyvanse is meant to provide once-a-day dosing since it regulates a slow release of d-amphetamine into the brain. Vyvanse is available as capsules, in six strengths: 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 50 mg, 60 mg, and 70 mg. The conversion rate of L-lysine-d-amphetamine dimesylate to d-amphetamine base is 0.2948, so a 30 mg-strength Vyvanse capsule is molecularly equivalent to 8.844 mg d-amphetamine base. However, this molecular equivalence would only hold true as a bioequivalence ratio if: the dimesylate salt instantly dissolved resulting in the complete dissociation of L-lysine-d-amphetamine ions, and then the covalent amide bond of every L-lysine-d-amphetamine molecule immediately underwent hydrolysis. In fact, being a prodrug, L-lysine-d-amphetamine has different properties than d-amphetamine; for instance, L-lysine-d-amphetamine is metabolised in the gastrointestinal tract, while d-amphetamine's metabolism is hepatic.[20]

Vyvanse is also being marketed for its lower abuse and misuse potential than when compared to similar drugs such as Adderall, Dexedrine, and the methylphenidate preparations, though it is still rated as a Schedule II drug by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Vyvanse has a significantly slower onset and its route of administration is limited to being taken orally, unlike many similar drugs which are commonly nasally insufflated to achieve a much faster onset and higher bioavailability. Since Vyvanse is a prodrug and thus not psychoactive it must be metabolized into d-amphetamine first before having psychoactive effects. Insufflation of Vyvanse is expected to produce no stimulant property, though this is disputed by the DEA.[citation needed]

[edit] Mixed amphetamine salts

Another pharmaceutical that contains dextroamphetamine is Adderall. The drug formulation of Adderall (both controlled and instant release forms) is:

-

- One-quarter racemic (d,l-)amphetamine aspartate monohydrate

- One-quarter dextroamphetamine saccharide

- One-quarter dextroamphetamine sulfate

- One-quarter racemic (d,l-)amphetamine sulfate

Aspartate, saccharate, and sulfate salts differ pharmacokinetically in the rate at which they are metabolized by the body. For this and other reasons, Adderall's effects are different from pharmaceuticals with dextroamphetamine as an exclusive active ingredient. Adderall is roughly three-quarters dextroamphetamine, with it accounting for 72.7% of the amphetamine base in Adderall (the remaining percentage is levoamphetamine). Adderall’s inclusion of levoamphetamine provides the pharmaceutical with a quicker onset and longer clinical effect compared to pharmaceuticals exclusively formulated of dextroamphetamine.[21] One study has shown that where the human brain has a preference for dextroamphetamine over levoamphetamine, it has been reported that certain children have a better clinical response to levoamphetamine.[22]

[edit] Uses

[edit] Clinical

- Approved for the treatment of ADHD and Narcolepsy.[23]

- Treatment for depression and weight-loss may be prescribed in rare treatment-resistant cases.[24] [25]

- In all clinical treatment scenarios, the dose of dextroamphetamine should be increased gradually from/by 2.5–5 mg/day every three days-week in order to help prevent abuse by minimizing the initial euphoria and effectively estimate the minimal dose required for each individual in treatment of the relevant condition.[26]

[edit] Experimental

Though such use remains out of the mainstream, dextroamphetamine has been successfully applied in the treatment of certain categories of depression as well as other psychiatric syndromes.[27] Such alternate uses include reduction of fatigue in cancer patients, antidepressant treatment for HIV patients with depression and debilitating fatigue,[28] and early stage physiotherapy for severe stroke victims.[29] If physical therapy patients take dextroamphetamine while they practice their movements for rehabilitation, they learn to move much faster than without dextroamphetamine, and in practice sessions with shorter lengths.[30]

[edit] Military

The U.S. Air Force uses dextroamphetamine as one of its two "go pills," given to pilots on long missions to help them remain focused and alert. (Conversely, the Air Force also issues "no-go pills"; prescription sedatives used after the mission to calm down.) [31][32][33] [1] The Tarnak Farm incident was linked by media reports to the use of this drug on long term fatigued pilots. A military tribunal did not accept this explanation, citing the lack of similar incidents. Newer stimulant medications with fewer side effects, like modafinil are being investigated and sometimes issued for this reason.[31]

[edit] Illicit

Along with Adderall and Ritalin, non-prescription use of dextroamphetamine has been reported for the feeling of elation (euphoria) and for use as a study aid, social aid and party drug. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, a large percentage of American college students reported illicit stimulant use in 2004.[34]

[edit] Famous users

- Priscilla Presley used it after Elvis gave it to her to stay awake during class.[citation needed]

- The English pop group Dexys Midnight Runners were named after Dexedrine, which was popularly used as a recreational drug among Northern Soul fans at the time.[citation needed]

- Johnny Cash is known for having abused dextroamphetamine for the majority of his career. Cash frequently mentions this abuse in his 1997 autobiography.[citation needed]

- Waylon Jennings is known to have used Dextroamphetamine during his early career, before switching to cocaine. He describes its use and his addiction in depth in his 1996 autobiography.[citation needed]

- In the Beatles Anthology documentary, Paul McCartney says that The Beatles used it during their early days to endure hours of playing at clubs in Hamburg, Germany.[citation needed]

- Hugh Hefner has spoken openly about his usage.

[edit] In fiction

- In the Left Behind series of Christian novels, dextroamphetamine (as Benzedrine or Dexedrine) is mentioned as a drug used to aid characters in regaining consciousness or staying awake after injury or fatigue.[citation needed]

- The main character, Case, in the William Gibson novel Neuromancer takes "Brazilian dex" in the form of octagon shaped pills.[citation needed]

- In the American television program Boston Legal, 2005: It Girls and Beyond, Denny Crane, a character with Alzheimer's disease, says he is taking dextroamphetamine.[citation needed]

- In "Bad Behavior" a collection of stories by Mary Gaitskill, Diane and Joey, two characters in the first story take Dexedrine three and a half days out of the week to stay awake. Joey is shown to have a bad appetite.[citation needed]

- Dexedrine is frequently taken by James Bond throughout the novels of Ian Flemming prior to planned, extended, physical exertion no reference to his drug use is portrayed in the films.[citation needed]

[edit] Pharmacology

Dextroamphetamine affects dopamine levels in a number of anatomical subsystems in brain, such as the caudate nucleus, the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. Because dextroamphetamine is a substrate analog at monoamine transporters, at all doses, dextroamphetamine prevents the reuptake of these neurotransmitters by competing with endogenous monoamines for uptake.[35] Transporter inhibition causes monoamines to remain in the synaptic cleft for a prolonged period (amphetamine inhibits monoamine reuptake in rats with a norepinephrine to dopamine ratio (NE:DA) of about 1:1 and a norepinephrine to 5-hydroxytryptamine ratio (NE:5-HT) of about 1:25).[36] At higher doses, when the concentration of dextroamphetamine is sufficient,[35] the drug can trigger direct release of norepinephrine and dopamine from the cytoplasmic transmitter pool.[37] That is, dextroamphetamine will cause norepinephrine and dopamine efflux via transporter proteins, functionally reversing transporter action, such that the transporters "pump out" catecholamines rather than taking them back up. This inversion leads to a release of large amounts of these transmitters from the cytoplasm of the presynaptic neuron into the synapse, causing increased stimulation of post-synaptic receptors and extreme euphoria. Dextroamphetamine releases monoamines in rats with selectivity ratios of about NE:DA = 1:3.5 and NE:5-HT = 1:250, meaning that NE and DA are readily released, but release of 5-HT does not occur unless the dose is extraordinarily high.[citation needed]

Dextroamphetamine does not alter glutamate levels in the prefrontal cortex. This may be because dextroamphetamine increases dopamine release in the prefrontal cortex; activation of the dopamine-2 receptors inhibits glutamate release in the prefrontal cortex. However, activation of the dopamine-1 receptors in the prefrontal cortex, increases glutamate leves in the nucleus accumbens. An increase of the glutamate levels in the nucleus accumbens may be part of the reason that dextroamphetamine has an ability to increase locomotor activity in rats. Serotonin may also play a role in dextroamphetamine's affect on glutamate levels; however, at therapeutic doses, dextroamphetamine would likely have little (if any) effect on the serotonin transporter (SERT).[38]

[edit] Pharmacokinetics

On average, about one half of a given dose is eliminated unchanged in the urine, while the other half is broken down into various metabolites (mostly benzoic acid).[39] However, the drug's half-life is highly variable because the rate of excretion is very sensitive to urinary pH. Under alkaline conditions, direct excretion is negligible and 95%+ of the dose is metabolized. Having an alkaline stomach will cause the drug to be absorbed faster through the stomach resulting in a higher blood level concentration of amphetamine. Having an alkaline bladder causes the drug to be excreted very slowly. It is possible with acute doses of sodium bicarbonate dissolved in water during amphetamine's course in the body for the half-life of the drug to last about 24 hours, with after effects lasting another 10 hours. The main metabolic pathway is d-amphetamine  phenylacetone

phenylacetone  benzoic acid

benzoic acid  hippuric acid. Another pathway, mediated by enzyme CYP2D6, is d-amphetamine

hippuric acid. Another pathway, mediated by enzyme CYP2D6, is d-amphetamine  p-hydroxyamphetamine

p-hydroxyamphetamine  p-hydroxynorephedrine. Although p-hydroxyamphetamine is a minor metabolite (~5% of the dose), it may have significant physiological effects as a norepinephrine analogue.[40]

p-hydroxynorephedrine. Although p-hydroxyamphetamine is a minor metabolite (~5% of the dose), it may have significant physiological effects as a norepinephrine analogue.[40]

Subjective effects are increased by larger doses, however, over the course of a given dose there is a noticeable divergence between such effects and drug concentration in the blood.[41] In particular, mental effects peak before maximal blood levels are reached, and decline as blood levels remain stable or even continue to increase.[42][43][44] This indicates a mechanism for development of acute tolerance, perhaps distinct from that seen in chronic use. Its slower onset of action as compared to methamphetamine and methylphenidate is presumably due to a somewhat lower effectiveness in crossing the blood-brain barrier.[45]

[edit] References

- ^ PHARMACEUTICAL MANUFACTURING ENCYCLOPEDIA Second Edition, Marshall Sittig, Volume 1, NOYES PUBLICATIONS

- ^ Castaneda R., Levy R., Hardy M., Trujillo M. (2000). "Alcohol & Drug Abuse: Long-Acting Stimulants for the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Disorder in Cocaine-Dependent Adults". Psychiatr Serv 51 (2): 169-171. PMID 10654994. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10654994.http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/51/2/169

- ^ a b Erowid Amphetamines Vault : Effects

- ^ Amphetamine; Facts

- ^ Amphetamines - Better Health Channel

- ^ adderall xr, adderall medication, adderall side effects, adderall abuse

- ^ Side Effects of Dexedrine (amphetamines; Biphetamine, Desoxyn dextroamphetamine sulfate)

- ^ Dextroamphetamine (Oral Route) - MayoClinic.com

- ^ Dexedrine | ADD ADHD Information Library

- ^ Dextroamphetamine

- ^ http://www.drugs.com/sfx/amphetamine-side-effects.html Side Effects drugs.com

- ^ Symptoms of Amphetamine withdrawal - WrongDiagnosis.com

- ^ Dextroamphetamine Withdrawals

- ^ Drug Abuse Help: Dexedrine Information

- ^ Miczek K (1979). "A new test for aggression in rats without aversive stimulation: differential effects of d-amphetamine and cocaine" (Abstract). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 60 (3): 253–9. doi:. PMID 108702. http://www.springerlink.com/content/v11jj22163t30326/.

- ^ Grilly D, Loveland A (2001). "What is a "low dose" of d-amphetamine for inducing behavioral effects in laboratory rats?". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 153 (2): 155–69. doi:. PMID 11205415.

- ^ Derlet R, Albertson T, Rice P (1990). "Antagonism of cocaine, amphetamine, and methamphetamine toxicity". Pharmacol Biochem Behav 36 (4): 745–9. doi:. PMID 2217500.

- ^ Derlet R, Albertson T, Rice P (1990). "The effect of SCH 23390 against toxic doses of cocaine, d-amphetamine and methamphetamine". Life Sci 47 (9): 821–7. doi:. PMID 2215083.

- ^ LS Goodman, A Gilman (1970). The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (7th ed.). New York: Macmillan Co..

- ^ FDA Approval of Vyvanse Pharmacological Reviews Pages 18 and 19

- ^ Glaser, et al. (2005). "Differential Effects of Amphetamine Isomers on Dopamine in the Rat Striatum and Nucleus Accumbens Core". Psychopharmacology 178: 250–258 (Pages: 255,256). doi:.

- ^ Arnold (2000). "Methylphenidate vs Amphetamine: Comparative Review". Journal of Attention Disorders 3 (4): 200–211. doi:.

- ^ GlaxoSmithKline Prescribing Information

- ^ Amphetamine; Dextroamphetamine extended-release capsules

- ^ Dexedrine Addiction

- ^ Dexedrine (dextroamphetamine sulfate)

- ^ Warneke L (1990). "Psychostimulants in psychiatry". Can J Psychiatry 35 (1): 3–10. PMID 2180548.

- ^ Wagner G, Rabkin R (2000). "Effects of dextroamphetamine on depression and fatigue in men with HIV: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". J Clin Psychiatry 61 (6): 436–40. PMID 10901342.

- ^ Martinsson L, Yang X, Beck O, Wahlgren N, Eksborg S (Sep-Oct 2003). "Pharmacokinetics of dexamphetamine in acute stroke". Clin Neuropharmacol 26 (5): 270–6. doi:. PMID 14520168.

- ^ Butefisch CM et al. (2002). "Modulation of Use-Dependent Plasticity by D-Amphetamine". Annals of Neurology 51 (1): 59–68. doi:. PMID 11782985.

- ^ a b Air Force scientists battle aviator fatigue

- ^ U.S. Pilots Stay Up Taking 'Uppers'

- ^ Emonson DL, Vanderbeek RD. (1995) The use of amphetamines in U.S. Air Force tactical operations during Desert Shield and Storm. 66(8):802

- ^ NIDA Notes Volume 20, Number 4 (March 2006)

- ^ a b Kuczenski R et al. (01 Feb 1995). "Hippocampus Norepinephrine, Caudate Dopamine and Serotonin, and Behavioral Responses to the Stereoisomers of Amphetamine and Methamphetamine". The Journal of Neuroscience 15 (2): 1308–1317. PMID 7869099. http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/reprint/15/2/1308.

- ^ Rothman, et al. "Amphetamine-Type Central Nervous System Stimulants Release Norepinephrine more Potently than they Release Dopamine and Serotonin." (2001): Synapse 39, 32–41 (Table V. on page 37)

- ^ Patrick, and Markowitz (1997). "Pharmacology of Methylphenidate, Amphetamine Enantiomers and Pemoline in Attention-Deificit Hyperacitivty Disorder". Human Psychopharmacology 12: 527–546 (Page:530). doi:.

- ^ Shoblock J, Sullivan E, Maisonneuve I, Glick S (2003). "Neurochemical and behavioral differences between d-methamphetamine and d-amphetamine in rats". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 165 (4): 359–69. doi:. PMID 12491026.

- ^ Mofenson H, Greensher J (1975). "Letter: Physostigmine as an antidote: use with caution". J Pediatr 87 (6 Pt 1): 1011–2. doi:. PMID 1185381.

- ^ Rangno R, Kaufmann J, Cavanaugh J, Island D, Watson J, Oates J (1973). "Effects of a false neurotransmitter, p-hydroxynorephedrine, on the function of adrenergic neurons in hypertensive patients" (Scanned copy). J Clin Invest 52 (4): 952–60. doi:. PMID 4348345. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=302343.

- ^ Asghar S, Tanay V, Baker G, Greenshaw A, Silverstone P (2003). "Relationship of plasma amphetamine levels to physiological, subjective, cognitive and biochemical measures in healthy volunteers". Hum Psychopharmacol 18 (4): 291–9. doi:. PMID 12766934.

- ^ Angrist B, Corwin J, Bartlik B, Cooper T (1987). "Early pharmacokinetics and clinical effects of oral D-amphetamine in normal subjects". Biol Psychiatry 22 (11): 1357–68. doi:. PMID 3663788.

- ^ Brown G, Hunt R, Ebert M, Bunney W, Kopin I (1979). "Plasma levels of d-amphetamine in hyperactive children. Serial behavior and motor responses" (Abstract). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 62 (2): 133–40. doi:. PMID 111276. http://www.springerlink.com/content/w14m559771164631/.

- ^ Brauer L, Ambre J, De Wit H (1996). "Acute tolerance to subjective but not cardiovascular effects of d-amphetamine in normal, healthy men". J Clin Psychopharmacol 16 (1): 72–6. doi:. PMID 8834422.

- ^ MacKenzie R, Heischober B (1997). "Methamphetamine". Pediatr Rev 18 (9): 305–9. doi:. PMID 9286149.

- Poison Information Monograph (PIM 178: Dexamphetamine Sulphate)

- Physician's 1991 Drug Handbook

- Dexamphetamine 1845887055 at GPnotebook

- Package inserts: "New Zealand". http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/Profs/Datasheet/d/Dexamphetaminesulphatetab.htm. "Canada". http://www.mentalhealth.com/drug/p30-d04.html.

- Yamada H, Baba T, Hirata Y, Oguri K, Yoshimura H (1984). "Studies on N-demethylation of methamphetamine by liver microsomes of guinea-pigs and rats: the role of flavin-containing mono-oxygenase and cytochrome P-450 systems". Xenobiotica 14 (11): 861–6. PMID 6506758.

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||