Resveratrol

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Resveratrol | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Other names | trans-3,5,4'-Trihydroxystilbene; 3,4',5-Stilbenetriol; trans-Resveratrol; (E)-5-(p-Hydroxystyryl)resorcinol (E)-5-(4-hydroxystyryl)benzene-1,3-diol |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 501-36-0 |

| SMILES |

|

| InChI |

|

| ChemSpider ID | |

| Properties | |

| Molecular formula | C14H12O3 |

| Molar mass | 228.25 |

| Appearance | white powder with slight yellow cast |

| Solubility in water | 0.03 g/L |

| Solubility in DMSO | 16 g/L |

| Solubility in ethanol | 50 g/L |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox references |

|

Resveratrol (trans-resveratrol) is a phytoalexin produced naturally by several plants when under attack by pathogens such as bacteria or fungi. Resveratrol has also been produced by chemical synthesis[1] and is sold as a nutritional supplement derived primarily from Japanese knotweed. In mouse and rat experiments, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, blood-sugar-lowering and other beneficial cardiovascular effects of resveratrol have been reported. Most of these results have yet to be replicated in humans. In the only positive human trial, extremely high doses (3–5 g) of resveratrol in a proprietary formulation have been necessary to significantly lower blood sugar.[2] Resveratrol is found in the skin of red grapes and is a constituent of red wine, but apparently not in sufficient amounts to explain the French paradox. Experiments have shown that resveratrol treatment extended the life of fruit flies, nematode worms and short living fish but it did not increase the life span of mice.

[edit] Life extension

The groups of Howitz and Sinclair reported in 2003 in the journal Nature that resveratrol significantly extends the lifespan of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.[3] Later studies conducted by Sinclair showed that resveratrol also prolongs the lifespan of the worm Caenorhabditis elegans and the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster.[4] In 2007, a different group of researchers was able to reproduce Sinclair's results with C. elegans,[5] but a third group could not achieve consistent increases in lifespan of D. melanogaster or C. elegans.[6]

In 2006, Italian scientists obtained the first positive result of resveratrol supplementation in a vertebrate. Using a short-lived fish, Nothobranchius furzeri, with a median life span of nine weeks, they found that a maximal dose of resveratrol increased the median lifespan by 56%. Compared with the control fish at nine weeks, that is by the end of the latter's life, the fish supplemented with resveratrol showed significantly higher general swimming activity and better learning to avoid an unpleasant stimulus. The authors noted a slight increase of mortality in young fish caused by resveratrol and hypothesized that it is its weak toxic action that stimulated the defense mechanisms and resulted in the life span extension.[7] Later the same year, Sinclair reported that resveratrol counteracted the detrimental effects of a high-fat diet in mice. The high fat diet was compounded by adding hydrogenated coconut oil to the standard diet; it provided 60% of energy from fat, and the mice on it consumed about 30% more calories than the mice on standard diet. Both the mice fed the standard diet and the high-fat diet plus 22 mg/kg resveratrol had a 30% lower risk of death than the mice on the high-fat diet. Gene expression analysis indicated the addition of resveratrol opposed the alteration of 144 out of 155 gene pathways changed by the high-fat diet. Insulin and glucose levels in mice on the high-fat+resveratrol diet were closer to the mice on standard diet than to the mice on the high-fat diet. However, addition of resveratrol to the high-fat diet did not change the levels of free fatty acids and cholesterol, which were much higher than in the mice on standard diet.[8] A further study by a group of scientists, which included Sinclair, indicated that resveratrol treatment had a range of beneficial effects in elderly mice but did not increase the longevity of ad libitum-fed mice when started midlife. [9]

[edit] Cancer prevention

In 1997, Jang reported that topical resveratrol applications prevented the skin cancer development in mice treated with a carcinogen.[10] There have since been dozens of studies of the anti-cancer activity of resveratrol in animal models.[11] No results of human clinical trials for cancer have been reported.[12] However, clinical trials to investigate the effects on colon cancer and melanoma (skin cancer) are currently recruiting patients.[13]

In vitro resveratrol interacts with multiple molecular targets (see the mechanisms of action), and has positive effects on the cells of breast, skin, gastric, colon, esophageal, prostate, and pancreatic cancer, and leukemia.[11] However, the study of pharmacokinetics of resveratrol in humans concluded that even high doses of resveratrol might be insufficient to achieve resveratrol concentrations required for the systemic prevention of cancer.[14] This is consistent with the results from the animal cancer models, which indicate that the in vivo effectiveness of resveratrol is limited by its poor systemic bioavailability.[15][16][12] The strongest evidence of anti-cancer action of resveratrol exists for tumors it can come into direct contact with, such as skin and gastrointestinal tract tumors. For other cancers, the evidence is equivocal, even if massive doses of resveratrol are used.[12]

Thus, topical application of resveratrol in mice, both before and after the UVB exposure, inhibited the skin damage and decreased skin cancer incidence. However, oral resveratrol was ineffective in treating mice inoculated with melanoma cells. Resveratrol given orally also had no effect on leukemia and lung cancer;[12][17] however, injected intraperitoneally, 2.5 or 10 mg/kg of resveratrol slowed the growth of metastatic Lewis lung carcinomas in mice.[12][18] Resveratrol (1 mg/kg orally) reduced the number and size of the esophageal tumors in rats treated with a carcinogen.[19] In several studies, small doses (0.02-8 mg/kg) of resveratrol, given prophylactically, reduced or prevented the development of intestinal and colon tumors in rats given different carcinogens.[12]

Resveratrol treatment appeared to prevent the development of mammary tumors in animal models; however, it had no effect on the growth of existing tumors. Paradoxically, treatment of pre-pubertal mice with high doses of resveratrol enhanced formation of tumors. Injected in high doses into mice, resveratrol slowed the growth of neuroblastomas.[12]

[edit] Athletic performance

Johan Auwerx (at the Institute of Genetics and Molecular and Cell Biology in Illkirch, France) and coauthors published an online article in the journal Cell in November, 2006. Mice fed resveratrol for fifteen weeks had better treadmill endurance than controls. The study supported Sinclair's hypothesis that the effects of resveratrol are indeed due to the activation of the Sirtuin 1 gene.

Nicholas Wade's interview-article with Dr. Auwerx[20] states that the dose was 400 mg/kg of body weight (much higher than the 22 mg/kg of the Sinclair study). For an 80 kg (176 lb) person, the 400 mg/kg of body weight amount used in Auwerx's mouse study would come to 32,000 mg/day. Compensating for the fact that humans have slower metabolic rates than mice would change the equivalent human dose to roughly 4571 mg/day. Again, there is no published evidence anywhere in the scientific literature of any clinical trial for efficacy in humans. There is limited human safety data (see above). Long-term safety has not been evaluated in humans.

In a study of 123 Finnish adults, those born with certain increased variations of the SIRT1 gene had faster metabolisms, helping them to burn energy more efficiently—indicating that the same pathway shown in the lab mice works in humans.[21]

[edit] Neurodegenerative disease

In November 2008, researchers at the Weill Medical College of Cornell University reported that dietary supplementation with resveratrol significantly reduced plaque formation in animal brains, a component of Alzheimer and other Neurodegenerative diseases.[22] In mice, oral resveratrol produced large reductions in brain plaque in the hypothalamus (-90%), striatum (-89%), and medial cortex (-48%) sections of the brain. In humans it is theorized that oral doses of resveratrol may reduce beta amyloid plaque associated with aging changes in the brain. Researchers theorize that one mechanism for plaque eradication is the ability of resveratrol to chelate (remove) copper.

[edit] Radiation protection

In a recent study by the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, it was found that resveratrol may offer protection against radiation exposure.[23]

[edit] Pharmacokinetics

The most efficient way of administering resveratrol in humans appears to be buccal delivery, that is without swallowing, by direct absorption through the inside of the mouth. When one mg of resveratrol in 50 mL solution was retained in the mouth for one min before swallowing, 37 ng/ml of free resveratrol were measured in plasma two minutes later. This level of unchanged resveratrol in blood can only be achieved with 250 mg of resveratrol taken in a pill form.[24]

About 70% of the resveratrol dose given orally as a pill is absorbed; nevertheless, oral bioavailability of resveratrol is low because it is rapidly metabolized in intestines and liver into conjugated forms: glucuronate and sulfonate.[25] Only trace amounts (below 5 ng/mL) of unchanged resveratrol could be detected in the blood after 25 mg oral dose.[25] Even when a very large dose of resveratrol (2.5 and 5 g) was given as an uncoated pill, the concentration of resveratrol in blood failed to reach the level necessary for the systemic cancer prevention.[26] However, resveratrol given in a proprietary formulation SRT-501 (3 or 5 g), developed by Sirtris Pharmaceuticals, reached 5-8 times higher blood levels. These levels did approach the concentration necessary to exert the effects shown in animal models and in vitro experiments.[2]

In humans[25] [26] and rats,[27][28][29] less than 5% of the oral dose is being observed as free resveratrol in blood plasma. The most abundant resveratrol metabolites in humans, rats, and mice are trans-resveratrol-3-O-glucuronide and trans-resveratrol-3-sulfate.[30] Walle suggests sulfate conjugates are the primary source of activity[25], Wang et al. suggests the glucuronides,[31] and Boocock et al. also emphasized the need for further study of the effects of the metabolites, including the possibility of deconjugation to free resveratrol inside cells. Goldberd, who studied the pharmacokinetics of resveratrol, catechin and quercetin in humans, concluded "it seems that the potential health benefits of these compounds based upon the in vitro activities of the unconjugated compounds are unrealistic and have been greatly exaggerated. Indeed, the profusion of papers describing such activities can legitimately be described as irrelevant and misleading. Henceforth, investigations of this nature should focus upon the potential health benefits of their glucuronide and sulfate conjugates."[32]

The hypothesis that resveratrol from wine could have higher bioavailability than resveratrol from a pill,[11][33] has been disproved by experimental data.[34][32] For example, after five men took 600 mL of red wine with the resveratrol content of 3.2 mg/L (total dose about 2 mg) before breakfast, unchanged resveratrol was detected in the blood of only two of them, and only in trace amounts (below 2.5 ng/mL). Resveratrol levels appeared to be slightly higher if red wine (600 mL of red wine containing 0.6 mg/mL resveratrol; total dose about 0.5 mg) was taken with meal: trace amounts (1–6 ng/mL) were found in four out of ten subjects.[34] In another study, the pharmacokinetics of resveratrol (25 mg) did not change whether it was taken with vegetable juice, white wine or white grape juice. The highest level of unchanged resveratrol in the serum (7-9 ng/mL) was achieved after thirty minutes, and it completely disappeared from blood after four hours.[32] The authors of both studies concluded that the trace amounts of resveratrol reached in the blood are insufficient to explain the French paradox. It appears that the beneficial effects of wine could be explained by the effects of alcohol[32] or the whole complex of substances wine contains[34]; for example, the cardiovascular benefits of wine appear to correlate with the content of procyanidins.[35]

[edit] Adverse effects and unknowns

While the health benefits of resveratrol seem promising, one study has theorized that it may stimulate the growth of human breast cancer cells, possibly because of resveratrol's chemical structure, which is similar to a phytoestrogen.[36][37] However, other studies have found that resveratrol actually fights breast cancer.[38][39] Some studies suggest that resveratrol slows the development of blood vessels, which suppresses tumors, but also slows healing.[40] Citing the evidence that resveratrol is estrogenic, some retailers of resveratrol advise that the compound may interfere with oral contraceptives and that women who are pregnant or intending to become pregnant should not use the product, while others advise that resveratrol should not be taken by children or young adults under eighteen, as no studies have shown how it affects their natural development.[41] A small study found that a single dose of up to 5 g of trans-resveratrol caused no serious adverse effects in healthy volunteers.[14]

[edit] Mechanisms of action

The mechanisms of resveratrol's apparent effects on life extension are not fully understood, but they appear to mimic several of the biochemical effects of calorie restriction. A new report indicates that resveratrol activates Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) and PGC-1α and improve functioning of the mitochondria.[42] Other research calls into question the theory connecting resveratrol, SIRT1, and calorie restriction.[43][44]

For the debate about Reseveratrol effects on longevity, please see calorie restriction page, "Sir2/SIRT1 and resveratrol" section.

A paper by Robb et al discusses resveratrol action in cells. It reports a fourteen-fold increase in the action of MnSOD (SOD2).[45] MnSOD reduces superoxide to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), but H2O2 is not increased due to other cellular activity. Superoxide O2- is a byproduct of respiration in complex 1 and 3 of the electron transport chain. It is "not highly toxic, [but] can extract an electron from biological membrane and other cell components, causing free radical chain reactions. Therefore it is essential for the cell to keep superoxide anions in check."[46] MnSOD reduces superoxide and thereby confers resistance to mitochondrial dysfunction, permeability transition, and apoptotic death in various diseases.[47] It has been implicated in lifespan extension, inhibits cancer, (e.g. pancreatic cancer [48][49]) and provides resistance to reperfusion injury and irradiation damage [50][51][52]. These effects have also been observed with resveratrol. Robb et al. propose MnSOD is increased by the pathway RESV → SIRT1 / NAD+ → FOXO3a → MnSOD. Resveratrol has been shown to cause SIRT1 to cause migration of FOXO transcription factors to the nucleus [53] which stimulates FOXO3a transcriptional activity [54] and it has been shown to enhance the sirtuin-catalyzed deacetylation (activity) of FOXO3a. MnSOD is known to be a target of FOXO3a, and MnSOD expression is strongly induced in cells overexpressing FOXO3a [55].

Resveratrol interferes with all three stages of carcinogenesis — initiation, promotion and progression. Experiments in cell cultures of varied types and isolated subcellular systems in vitro imply many mechanisms in the pharmacological activity of resveratrol. These mechanisms include modulation of the transcription factor NF-kB,[56] inhibition of the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme CYP1A1[57] (although this may not be relevant to the CYP1A1-mediated bioactivation of the procarcinogen benzo(a)pyrene[58]), alterations in androgenic[59] actions and expression and activity of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. In vitro, resveratrol "inhibited the proliferation of human pancreatic cancer cell lines." In some lineages of cancer cell culture, resveratrol has been shown to induce apoptosis, which means it kills cells and may kill cancer cells.[59][60][61][62][63][64] Resveratrol has been shown to induce Fas/Fas ligand mediated apoptosis, p53 and cyclins A, B1 and cyclin-dependent kinases cdk 1 and 2. Resveratrol also possesses antioxidant and anti-angiogenic properties.[65][66]

Resveratrol was reported effective against neuronal cell dysfunction and cell death, and in theory could help against diseases such as Huntington's disease and Alzheimer's disease.[67][68] Again, this has not yet been tested in humans for any disease.

Research at the Northeastern Ohio Universities College of Medicine and Ohio State University indicates that resveratrol has direct inhibitory action on cardiac fibroblasts, and may inhibit the progression of cardiac fibrosis.[69]

According to Patrick Arnold, it also significantly increases natural testosterone production from being both a selective estrogen receptor modulator[70][71] and an aromatase inhibitor.[72][73]

In December 2007, work from Irfan Rahman's laboratory at the University of Rochester demonstrated that resveratrol increased intracellular glutathione levels via Nrf2-dependent upregulation of gamma-glutamylcysteine ligase in lung epithelial cells, which protected them against cigarette smoke extract induced oxidative stress.[74]

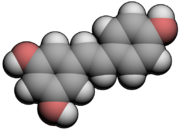

[edit] Chemical and physical properties

Resveratrol (3,5,4'-trihydroxystilbene) is a polyphenolic phytoalexin. It is a stilbenoid, a derivate of stilbene, and is produced in plants with the help of the enzyme stilbene synthase.

It exists as two geometric isomers: cis- (Z) and trans- (E), with the trans-isomer shown in the top image. The trans- form can undergo isomerisation to the cis- form when exposed to ultraviolet irradiation.[75] Trans-resveratrol in the powder form was found to be stable under "accelerated stability" conditions of 75% humidity and 40 degrees C in the presence of air.[76] Resveratrol content also stayed stable in the skins of grapes and pomace taken after fermentation and stored for a long period.[77]

[edit] Plants and foods

Resveratrol was originally isolated by Takaoka from the roots of white hellebore in 1940, and later, in 1963, from the roots of Japanese knotweed. However, it attracted wider attention only in 1992, when its presence in wine was suggested as the explanation for cardioprotective effects of wine.[11]

In grapes, resveratrol is found primarily in the skin,[78] and — in muscadine grapes — also in the seeds.[79] The amount found in grape skins also varies with the grape cultivar, its geographic origin, and exposure to fungal infection. The amount of fermentation time a wine spends in contact with grape skins is an important determinant of its resveratrol content.[78]

The levels of resveratrol found in food varies greatly. Red wine contains between 0.2 and 5.8 mg/L,[80] depending on the grape variety, while white wine has much less — the reason being that red wine is fermented with the skins, allowing the wine to absorb the resveratrol, whereas white wine is fermented after the skin has been removed.[78] A number of reports have indicated that muscadine grapes may contain high concentrations of resveratrol and that wines produced from these grapes, both red and white, may contain more than 40 mg/L.[81][79] However, subsequent studies have found little or no resveratrol in different varieties of muscadine grapes.[82][83]

The fruit of the mulberry (esp. the skin[84]) is a source, and sold as a nutritional supplement.

[edit] Content in wines and grape juice

| Beverage | Total resveratrol (mg/L)[78][79] | Total resveratrol in 150 mL wine (mg)[78][79] |

|---|---|---|

| Red Wines (Global) | 1.98 - 7.13 | 0.30 - 1.07 |

| Red Wines (Spanish) | 1.92 - 12.59 | 0.29 - 1.89 |

| Red grape juice (Spanish) | 1.14 - 8.69 | 0.17 - 1.30 |

| Rose Wines (Spanish) | 0.43 - 3.52 | 0.06 - 0.53 |

| Pinot Noir | 0.40 - 2.0 | 0.06 - 0.30 |

| White Wines (Spanish) | 0.05 - 1.80 | 0.01 - 0.27 |

The trans-resveratrol concentration in forty Tuscan wines ranged from 0.3 to 2.1 mg/L in the 32 red wines tested and had a maximum of 0.1 mg/L in the 8 white wines in the test. Both the cis- and trans-isomers of resveratrol were detected in all tested samples. cis-Resveratrol levels were comparable to those of the trans-isomer. They ranged from 0.5 mg/L to 1.9 mg/L in red wines and had a maximum of 0.2 mg/L in white wines.[85]

In a review of published resveratrol concentrations, the average resveratrol concentration in red wines is 1.9 ± 1.7 mg trans-resveratrol/l (8.2 ± 7.5 μM), ranging from non-detectable levels to 14.3 mg/l (62.7 μM) trans-resveratrol. Levels of cis-resveratrol follow the same trend as trans-resveratrol.[86]

Reports suggest that some aspect of the wine making process converts piceid to resveratrol in wine, as wine seems to have twice the average resveratrol concentration of the equivalent commercial juices.[79]

In general, wines made from grapes of the Pinot Noir and St. Laurent varieties showed the highest level of trans-resveratrol, though no wine or region can yet be said to produce wines with significantly higher resveratrol concentrations than any other wine or region.[86]

[edit] Content in selected foods

| Food | Serving | Total resveratrol (mg)[87] |

|---|---|---|

| Peanuts (raw) | 1 c (146 g) | 0.01 - 0.26 |

| Peanuts (boiled) | 1 c (180 g) | 0.32 - 1.28 |

| Peanut butter | 1 c (258 g) | 0.04 - 0.13 |

| Red grapes | 1 c (160 g) | 0.24 - 1.25 |

Ounce for ounce, peanuts have about half the amount of resveratrol as that found in red wine. The average amount of resveratrol in one ounce of peanuts in the marketplace (about 15 whole) is 79.4 µg/ounce.

In comparison, some red wines contain approximately 160 µg/fluid ounce.[88] Resveratrol was detected in grape, cranberry, and wine samples. Concentrations ranged from 1.56 to 1042 nmol/g in Concord grape products, and from 8.63 to 24.84 micromol/L in Italian red wine. The concentrations of resveratrol were similar in cranberry and grape juice at 1.07 and 1.56 nmol/g, respectively.[89]

Blueberries have about twice as much resveratrol as bilberries, but there is great regional variation. These fruits have less than ten percent of the resveratrol of grapes. Cooking or heat processing of these berries will contribute to the degradation of resveratrol, reducing it by up to half. [90]

[edit] Supplementation

Resveratrol nutritional supplements, first sourced from ground dried grape skins and seeds, are now primarily derived from the less expensive, more concentrated Japanese knotweed, which contains up to 187 mg/kg in the dried root and can be concentrated in an extract up to 50%.[91]

As a result of extensive news coverage,[92][93] sales of supplements greatly increased in 2006,[94][95] despite cautions that benefits to humans are unproven.[96][95][97]

[edit] Related compounds

[edit] See also

[edit] Other articles

|

[edit] References

- ^ Farina A, Ferranti C, Marra C (2006). "An improved synthesis of resveratrol". Nat. Prod. Res. 20 (3): 247–52. doi:. PMID 16401555.

- ^ a b Elliott PJ, Jirousek, M. (2008). "Sirtuins: Novel targets for metabolic disease". Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs 9 (4): 1472–4472. PMID 18393104.

- ^ Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA (2003). "Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan" (PDF). Nature 425 (6954): 191–196. doi:. PMID 12939617. http://www.fiestaterrace.com/dlamming/nature2003.pdf.

- ^ Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu1 S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D (2004). "Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay aging in metazoans" (PDF). Nature 430 (7000): 686–9. doi:. PMID 15254550. http://sinclairfs.med.harvard.edu/pdfs/nature2004.pdf.

- ^ Gruber J, Tang SY, Halliwell B (April 2007). "Evidence for a trade-off between survival and fitness caused by resveratrol treatment of Caenorhabditis elegans". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1100: 530–42. doi:. PMID 17460219.

- ^ Bass TM, Weinkove D, Houthoofd K, Gems D, Partridge L. (2007). "Effects of resveratrol on lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans". Mechanisms of ageing and development 128 (10): 546–52. doi:. PMID 17875315.

- ^ Valenzano DR, Terzibasi E, Genade T, Cattaneo A, Domenici L, Cellerino A (2006). "Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate". Current Biology 16 (3): 296–300. doi:. PMID 16461283.

- ^ Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, Prabhu VV, Allard JS, Lopez-Lluch G, Lewis K, Pistell PJ, Poosala S, Becker KG, Boss O, Gwinn D, Wang M, Ramaswamy S, Fishbein KW, Spencer RG, Lakatta EG, Le Couteur D, Shaw RJ, Navas P, Puigserver P, Ingram DK, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA (2006). "Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet". Nature 444 (7117): 337–42. doi:. PMID 17086191.

- ^ Pearson KJ, et al. (2008). "Resveratrol delays age-related deterioration and mimics transcriptional aspects of dietary restriction without extending life span". Cell Metab 8 (2): 157–68. doi:. PMID 18599363.

- ^ Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CW, Fong HH, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM (1997). "Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes". Science 275 (5297): 218–20. doi:. PMID 8985016.

- ^ a b c d See review:Baur JA, Sinclair DA (2006). "Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence". Nat Rev Drug Discov 5 (6): 493–506. doi:. PMID 16732220.

- ^ a b c d e f g See review:Athar M, Back JH, Tang X, et al (November 2007). "Resveratrol: a review of preclinical studies for human cancer prevention". Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 224 (3): 274–83. doi:. PMID 17306316.

- ^ Resveratrol. From Clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Boocock DJ, Faust GE, Patel KR, et al (June 2007). "Phase I dose escalation pharmacokinetic study in healthy volunteers of resveratrol, a potential cancer chemopreventive agent". Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 16 (6): 1246–52. doi:. PMID 17548692.

- ^ Niles RM, Cook CP, Meadows GG, Fu YM, McLaughlin JL, Rankin GO (October 2006). "Resveratrol is rapidly metabolized in athymic (nu/nu) mice and does not inhibit human melanoma xenograft tumor growth". J. Nutr. 136 (10): 2542–6. PMID 16988123. PMC: 1612582. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16988123.

- ^ Wenzel E, Soldo T, Erbersdobler H, Somoza V (May 2005). "Bioactivity and metabolism of trans-resveratrol orally administered to Wistar rats". Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (5): 482–94. doi:. PMID 15779067.

- ^ Gao X, Xu YX, Divine G, Janakiraman N, Chapman RA, Gautam SC (July 2002). "Disparate in vitro and in vivo antileukemic effects of resveratrol, a natural polyphenolic compound found in grapes". J. Nutr. 132 (7): 2076–81. PMID 12097696. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12097696.

- ^ Kimura Y, Okuda H (June 2001). "Resveratrol isolated from Polygonum cuspidatum root prevents tumor growth and metastasis to lung and tumor-induced neovascularization in Lewis lung carcinoma-bearing mice". J. Nutr. 131 (6): 1844–9. PMID 11385077. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11385077.

- ^ Li ZG, Hong T, Shimada Y, Komoto I, Kawabe A, Ding Y, Kaganoi J, Hashimoto Y, Imamura M (2002). "Suppression of N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine (NMBA)-induced esophageal tumorigenesis in F344 rats by resveratrol". Carcinogenesis 23 (9): 1531–6. doi:. PMID 12189197.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (November 16 2006). "Red Wine Ingredient Increases Endurance, Study Shows". New York Times.

- ^ Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, et al (2006). "Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha". Cell 127 (6): 1109–22. doi:. PMID 17112576.

- ^ Karuppagounder SS, Pinto JT, Xu H, Chen HL, Beal MF, Gibson GE (November 2008). "Dietary supplementation with resveratrol reduces plaque pathology in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease". Neurochem Int.. doi:. PMID 19041676.

- ^ Plant Antioxidant May Protect Against Radiation Exposure Science Daily September 24, 2008

- ^ Asensi M, Medina I, Ortega A, et al (August 2002). "Inhibition of cancer growth by resveratrol is related to its low bioavailability". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 33 (3): 387–98. doi:. PMID 12126761. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0891584902009115.

- ^ a b c d Walle T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE, Walle UK (2004). "High absorption but very low bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans". Drug Metab. Dispos. 32 (12): 1377–82. doi:. PMID 15333514.

- ^ a b David J. Boocock, et al (2007). "Phase I Dose Escalation Pharmacokinetic Study in Healthy Volunteers of Resveratrol, a Potential Cancer Chemopreventive Agent". Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 16 (6): 1246–1252. doi:. PMID 17548692.

- ^ Marier JF, Vachon P, Gritsas A, Zhang J, Moreau JP, Ducharme MP (2002). "Metabolism and disposition of resveratrol in rats: extent of absorption, glucuronidation, and enterohepatic recirculation evidenced by a linked-rat model". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 302 (1): 369–73. doi:. PMID 12065739.

- ^ Abd El-Mohsen M, Bayele H, Kuhnle G, et al (July 2006). "Distribution of [3H]trans-resveratrol in rat tissues following oral administration". Br J Nutr. 96 (1): 62–70. doi:. PMID 16869992.

- ^ Wenzel E, Soldo T, Erbersdobler H, Somoza V (May 2005). "Bioactivity and metabolism of trans-resveratrol orally administered to Wistar rats". Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (5): 482–94. doi:. PMID 15779067.

- ^ Yu C, Shin YG, Chow A, et al (December 2002). "Human, rat, and mouse metabolism of resveratrol". Pharm Res. 19 (12): 1907–14. doi:. PMID 12523673. http://www.kluweronline.com/art.pdf?issn=0724-8741&volume=19&page=1907.

- ^ Wang LX, Heredia A, Song H, et al (October 2004). "Resveratrol glucuronides as the metabolites of resveratrol in humans: characterization, synthesis, and anti-HIV activity". J Pharm Sci 93 (10): 2448–57. doi:. PMID 15349955.

- ^ a b c d Goldberg DM, Yan J, Soleas GJ (February 2003). "Absorption of three wine-related polyphenols in three different matrices by healthy subjects". Clin. Biochem. 36 (1): 79–87. doi:. PMID 12554065. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0009912002003971.

- ^ Wenzel E, Somoza V (May 2005). "Metabolism and bioavailability of trans-resveratrol". Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (5): 472–81. doi:. PMID 15779070.

- ^ a b c Vitaglione P, Sforza S, Galaverna G, et al (May 2005). "Bioavailability of trans-resveratrol from red wine in humans". Mol Nutr Food Res 49 (5): 495–504. doi:. PMID 15830336.

- ^ Corder R, Mullen W, Khan NQ, et al (November 2006). "Oenology: red wine procyanidins and vascular health". Nature 444 (7119): 566. doi:. PMID 17136085.

- ^ Gehm BD, McAndrews JM, Chien PY, Jameson JL (December 1997). "Resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound found in grapes and wine, is an agonist for the estrogen receptor". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94 (25): 14138–43. doi:. PMID 9391166. PMC: 28446. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9391166.

- ^ Bowers JL, Tyulmenkov VV, Jernigan SC, Klinge CM (October 2000). "Resveratrol acts as a mixed agonist/antagonist for estrogen receptors alpha and beta". Endocrinology 141 (10): 3657–67. doi:. PMID 11014220. http://endo.endojournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11014220.

- ^ Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, Ghidoni R, Ferraroni M, La Vecchia C (April 2005). "Resveratrol and breast cancer risk". Eur J Cancer Prev. 14 (2): 139–42. doi:. PMID 15785317. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0959-8278&volume=14&issue=2&spage=139.

- ^ Garvin S, Ollinger K, Dabrosin C (January 2006). "Resveratrol induces apoptosis and inhibits angiogenesis in human breast cancer xenografts in vivo". Cancer Lett. 231 (1): 113–22. doi:. PMID 16356836.

- ^ Bråkenhielm E, Cao R, Cao Y (August 2001). "Suppression of angiogenesis, tumor growth, and wound healing by resveratrol, a natural compound in red wine and grapes". Faseb J. 15 (10): 1798–800. doi:. PMID 11481234. http://www.fasebj.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11481234.

- ^ More resveratrol information, What is Resveratrol?.[1]

- ^ Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, et al (December 2006). "Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α". Cell 127 (6): 1109–22. doi:. PMID 17112576.

- ^ Kaeberlein M, Kirkland KT, Fields S, Kennedy BK (September 2004). "Sir2-independent life span extension by calorie restriction in yeast". PLoS Biol. 2 (9): E296. doi:. PMID 15328540.

- ^ Kaeberlein M, McDonagh T, Heltweg B, et al (April 2005). "Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol". J Biol Chem. 280 (17): 17038–45. doi:. PMID 15684413.

- ^ Robb EL, Page MM, Wiens BE, Stuart JA (March 2008). "Molecular mechanisms of oxidative stress resistance induced by resveratrol: Specific and progressive induction of MnSOD". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 367 (2): 406–12. doi:. PMID 18167310.

- ^ Zsolt Radák, Free Radicals in Exercise and Aging, 2000, p39

- ^ Macmillan-Crow LA, Cruthirds DL (April 2001). "Invited review: manganese superoxide dismutase in disease". Free Radic Res. 34 (4): 325–36. doi:. PMID 11328670.

- ^ Cullen JJ, Weydert C, Hinkhouse MM, et al (15 March 2003). "The role of manganese superoxide dismutase in the growth of pancreatic adenocarcinoma". Cancer Res. 63 (6): 1297–303. PMID 12649190. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12649190.

- ^ "Mounting Evidence Shows Red Wine Antioxidant Kills Cancer". Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Rochester Medical Center.. 2008-03-26. http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-03/uorm-mes032508.php#. Retrieved on 2008-03-26.

- ^ Sun J, Folk D, Bradley TJ, Tower J (01 June 2002). "Induced overexpression of mitochondrial Mn-superoxide dismutase extends the life span of adult Drosophila melanogaster". Genetics 161 (2): 661–72. PMID 12072463. PMC: 1462135. http://www.genetics.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12072463.

- ^ Hu D, Cao P, Thiels E, et al (March 2007). "Hippocampal long-term potentiation, memory, and longevity in mice that overexpress mitochondrial superoxide dismutase". Neurobiol Learn Mem 87 (3): 372–84. doi:. PMID 17129739.

- ^ Wong GH (May 1995). "Protective roles of cytokines against radiation: induction of mitochondrial MnSOD". Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1271 (1): 205–9. PMID 7599209.

- ^ Stefani M, Markus MA, Lin RC, Pinese M, Dawes IW, Morris BJ (October 2007). "The effect of resveratrol on a cell model of human aging". Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1114: 407–18. doi:. PMID 17804521.

- ^ Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, et al (March 2004). "Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase". Science 303 (5666): 2011–5. doi:. PMID 14976264.

- ^ Kops GJ, Dansen TB, Polderman PE, et al (September 2002). "Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a protects quiescent cells from oxidative stress". Nature 419 (6904): 316–21. doi:. PMID 12239572.

- ^ Leiro J, Arranz JA, Fraiz N, Sanmartín ML, Quezada E, Orallo F (2005). "Effect of cis-resveratrol on genes involved in nuclear factor kappa B signaling". Int. Immunopharmacol. 5 (2): 393–406. doi:. PMID 15652768.

- ^ Chun YJ, Kim MY, Guengerich FP (1999). "Resveratrol is a selective human cytochrome P450 1A1 inhibitor". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 262 (1): 20–4. doi:. PMID 10448061.

- ^ Schwarz D, Roots I (2003). "In vitro assessment of inhibition by natural polyphenols of metabolic activation of procarcinogens by human CYP1A1". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 303 (3): 902–7. doi:. PMID 12670496.

- ^ a b Benitez DA, Pozo-Guisado E, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Fernandez-Salguero PM, Castellon EA (October 18 2006). "Mechanisms involved in resveratrol-induced apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in prostate cancer-derived cell lines". Journal of Andrology 28: 282. doi:. PMID 17050787.

- ^ Faber AC, Chiles TC (December 2006). "Resveratrol induces apoptosis in transformed follicular lymphoma OCI-LY8 cells: Evidence for a novel mechanism involving inhibition of BCL6 signaling". International Journal of Oncology 29 (6): 1561–6. PMID 17088997.

- ^ Riles WL, Erickson J, Nayyar S, Atten MJ, Attar BM, Holian O (21 September 2006). "Resveratrol engages selective apoptotic signals in gastric adenocarcinoma cells". World Journal of Gastroenterology 12 (35). PMID 17007014.

- ^ Sareen D, van Ginkel PR, Takach JC, Mohiuddin A, Darjatmoko SR, Albert DM, Polans AS (September 2006). "Mitochondria as the primary target of resveratrol-induced apoptosis in human retinoblastoma cells". Investigative Ophthamology & Visual Science 47 (9). PMID 16936077.

- ^ Tang HY, Shih A, Cao HJ, Davis FB, Davis PJ, Lin HY (August 2006). Resveratrol-induced cyclooxygenase-2 facilitates p53-dependent apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. 5. PMID 16928824.

- ^ Aziz MH, Nihal M, Fu VX, Jarrard DF, Ahmad N (May 2006). "Resveratrol-caused apoptosis of human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells is mediated via modulation of phosphatidylinositol 3'-kinase/Akt pathway and Bcl-2 family proteins". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 5 (5): 1335. doi:. PMID 16731767.

- ^ Cao Y, Fu ZD, Wang F, Liu HY, Han R (2005). "Anti-angiogenic activity of resveratrol, a natural compound from medicinal plants". Journal of Asian natural products research 7 (3): 205–13. doi:. PMID 15621628.

- ^ Hung LM, Chen JK, Huang SS, Lee RS, Su MJ (2000). "Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes". Cardiovasc. Res. 47 (3): 549–55. doi:. PMID 10963727.

- ^ Parker JA, Arango M, Abderrahmane S, et al (April 2005). "Resveratrol rescues mutant polyglutamine cytotoxicity in nematode and mammalian neurons". Nat Genet. 37 (4): 349–50. doi:. PMID 15793589.

- ^ Marambaud P, Zhao H, Davies P (November 2005). "Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer's disease amyloid-beta peptides". J Biol Chem. 280 (45): 37377–82. doi:. PMID 16162502.

- ^ Olson ER, Naugle JE, Zhang X, Bomser JA, Meszaros JG (March 2005). "Inhibition of cardiac fibroblast proliferation and myofibroblast differentiation by resveratrol". Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 288 (3): H1131–8. doi:. PMID 15498824.

- ^ Juan ME, González-Pons E, Munuera T, Ballester J, Rodríguez-Gil JE, Planas JM (2005). "trans-Resveratrol, a natural antioxidant from grapes, increases sperm output in healthy rats". J Nutr. 135 (4): 757–60. PMID 15795430.

- ^ Bhat KP, Lantvit D, Christov K, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM (2001). "Estrogenic and antiestrogenic properties of resveratrol in mammary tumor models". Cancer Res. 61 (20): 7456–63. PMID 11606380.

- ^ Wang Y, Lee KW, Chan FL, Chen S, Leung LK (2006). "The red wine polyphenol resveratrol displays bilevel inhibition on aromatase in breast cancer cells". Toxicol Sci. 92 (1): 71–7. doi:. PMID 16611627.

- ^ Leder BZ, Rohrer JL, Rubin SD, Gallo J, Longcope C (2004). "Effects of aromatase inhibition in elderly men with low or borderline-low serum testosterone levels". J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89 (3): 1174–80. doi:. PMID 15001605.

- ^ Kode A, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Yang SR, Megson IL, Rahman I (March 2008). "Resveratrol induces glutathione synthesis by activation of Nrf2 and protects against cigarette smoke-mediated oxidative stress in human lung epithelial cells". Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 294 (3): L478–88. doi:. PMID 18162601.

- ^ Lamuela-Raventos, RM (1995). "Direct HPLC Analysis of cis- and trans-Resveratrol and Piceid Isomers in Spanish Red Vitis vinifera Wines" ([dead link] – Scholar search). J. Agric. Food Chem. (pubs.acs.org) 43 (43): 281–283. doi:. http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi/jafcau/1995/43/i02/f-pdf/f_jf00050a003.pdf?sessid=6006l3.

- ^ Prokop J, Abrman P, Seligson AL, Sovak M (2006). "Resveratrol and its glycon piceid are stable polyphenols". J Med Food 9 (1): 11–4. doi:. PMID 16579722.

- ^ Bertelli AA, Gozzini A, Stradi R, Stella S, Bertelli A (1998). "Stability of resveratrol over time and in the various stages of grape transformation". Drugs Exp Clin Res 24 (4): 207–11. PMID 10051967.

- ^ a b c d e Roy, H., Lundy, S., Resveratrol, Pennington Nutrition Series, 2005 No. 7

- ^ a b c d e LeBlanc, Mark Rene (2005-12-13). "Cultivar, Juice Extraction, Ultra Violet Irradiation and Storage Influence the Stilbene Content of Muscadine Grapes (Vitis Rotundifolia Michx.)". http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-01202006-082858/. Retrieved on 2007-08-15.

- ^ Gu X, Creasy L, Kester A, Zeece M (August 1999). "Capillary electrophoretic determination of resveratrol in wines". J Agric Food Chem. 47 (8): 3223–7. doi:. PMID 10552635.

- ^ Ector BJ, Magee JB, Hegwood CP, Coign MJ., Resveratrol Concentration in Muscadine Berries, Juice, Pomace, Purees, Seeds, and Wines.

- ^ Pastrana-Bonilla E, Akoh CC, Sellappan S, Krewer G (August 2003). "Phenolic content and antioxidant capacity of muscadine grapes". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (18): 5497–503. doi:. PMID 12926904. "Contrary to previous results, ellagic acid and not resveratrol was the major phenolic in muscadine grapes. The HPLC solvent system used coupled with fluorescence detection allowed separation of ellagic acid from resveratrol and detection of resveratrol." "trans-resveratrol had the lowest concentrations of the detected phenolics, ranging from not detected in two varieties to 0.2 mg/ 100 g of FW (Tables 1 and 2). Our result for resveratrol differed from previous results [Ector et al., 1996] indicating high concentrations. These researchers apparently were not able to separate ellagic acid from resveratrol with UV detection alone.".

- ^ Hudson TS, Hartle DK, Hursting SD, et al (September 2007). "Inhibition of prostate cancer growth by muscadine grape skin extract and resveratrol through distinct mechanisms". Cancer Res. 67 (17): 8396–405. doi:. PMID 17804756. "MSKE [muscadine grape skin extract] does not contain significant quantities of resveratrol and differs from MSEE. To determine whether MSKE contains significant levels of resveratrol and to compare the chemical content of MSKE (skin) with MSEE (seed), HPLC analyses were done. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. S1A and B, MSKE does not contain significant amounts of resveratrol (<1 ?g/g by limit of detection).".

- ^ Stewart JR, Artime MC, O'Brian CA (01 July 2003). "Resveratrol: a candidate nutritional substance for prostate cancer prevention". J Nutr. 133 (7 Suppl): 2440S–2443S. PMID 12840221. http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/full/133/7/2440S.

- ^ Mozzon, M. (1996). "Resveratrol content in some Tuscan wines". Ital. J. Food sci. (Chiriotti, Pinerolo, ITALIE) 8 (2): 145–52. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=3123149. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ^ a b Stervbo, U.; Vang, O.; Bonnesen, C. (2007). "A review of the content of the putative chemopreventive phytoalexin resveratrol in red wine". Food Chemistry 101 (2): 449–57. doi:.

- ^ Higdon, Jane (2005). "Resveratrol". Oregon State University. The Linus Pauling Institute Micronutrient Information Center. http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/infocenter/phytochemicals/resveratrol/. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

- ^ "Resveratrol". The Peanut Institute. 1999. http://www.peanut-institute.org/kidsFFT.html. Retrieved on 2008-01-28.

- ^ Wang Y, Catana F, Yang Y, Roderick R, van Breemen RB (2002). "An LC-MS method for analyzing total resveratrol in grape juice, cranberry juice, and in wine". J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 (3): 431–5. doi:. PMID 11804508.

- ^ Lyons MM, Yu C, Toma RB, et al (2003). "Resveratrol in raw and baked blueberries and bilberries". J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (20): 5867–70. doi:. PMID 13129286.

- ^ Resveratrol Information

- ^ Rimas, Andrew (2006-12-11). "MOLECULAR BIOLOGIST DAVID SINCLAIR, MEETING THE MINDS". Boston Globe (boston.com). http://www.boston.com/news/globe/health_science/articles/2006/12/11/his_research_targets_the_aging_process/. Retrieved on 2007-06-22.

- ^ Stipp, David (2007-01-19). "Can red wine help you live forever?". Fortune magazine (CNN): pp. 3. http://money.cnn.com/2007/01/18/magazines/fortune/Live_forever.fortune/index.htm?postversion=2007011912. Retrieved on 2007-08-15.

- ^ "MM2 Group Announces Record Sales of Its Resveratrol Grape Powder". MM2 Group (Earthtimes.org). 2006-11-29. http://www.earthtimes.org/articles/show/news_press_release,27694.shtml. Retrieved on 2007-06-22.

- ^ a b Zachary M. Seward (2006-11-30). "Quest for youth drives craze for 'wine' pills" (htm). The Wall Street Journal. http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/06334/742471-114.stm. Retrieved on 2008-02-02.

- ^ "[dead link] Caution urged with resveratrol". United Press International (Upi.com). 2006-11-30. http://www.upi.com/NewsTrack/Science/2006/11/30/caution_urged_with_resveratrol/9504/[dead link]. Retrieved on 2007-06-21.

- ^ Aleccia, JoNel (2008-04-22). "Longevity quest moves slowly from lab to life". MSNBC (msnbc.com). http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23359040/. Retrieved on 2008-04-22.

[edit] Further reading

- Gescher AJ, Steward WP (01 October 2003). "Relationship between mechanisms, bioavailibility, and preclinical chemopreventive efficacy of resveratrol: a conundrum". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 12 (10): 953–7. PMID 14578128. http://cebp.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/full/12/10/953.

- Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, et al (July 2004). "Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase". Science 305 (5682): 390–2. doi:. PMID 15205477.

- Wolf G (February 2006). "Calorie restriction increases life span: a molecular mechanism". Nutr Rev. 64 (2 Pt 1): 89–92. doi:. PMID 16536186. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/resolve/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0029-6643&date=2006&volume=64&issue=2%20Pt%201&spage=89.

[edit] External links

- Félicien Breton (2008). "Which wines have the most health benefits". http://www.frenchscout.com/polyphenols.

- CTD's Resveratrol page from the Comparative Toxicogenomics Database

- PDRHealth Resveratrol

- Sirtris Pharmaceuticals

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||