Marvel Comics

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

| Type | Private (subsidiary) |

|---|---|

| Genre | Crime, horror, mystery, romance, science fiction, war, Western |

| Founded | 1939 as Timely Comics |

| Founder(s) | Martin Goodman |

| Headquarters | 417 5th Avenue, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Area served | Worldwide |

| Key people | Joe Quesada, Editor-in-chief Dan Buckley, Publisher, C.O.O. |

| Industry | Publishing |

| Products | Comics/See list of Marvel Comics publications |

| Revenue | US$125,700,000 (2007) ▲ |

| Operating income | US$53,500,000 (2007) ▲ [1] |

| Parent | Marvel Entertainment |

| Divisions | Marvel UK Epic Comics Star Comics |

| Website | marvel.com |

Marvel Comics is an American comic book and related media company owned by Marvel Publishing, Inc., a subsidiary of Marvel Entertainment, Inc.[2] Marvel counts among its characters such well-known properties as Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Thor, Iron Man, Captain America, the X-Men, and many others. Most of Marvel's fictional characters operate in one single reality; this is known as the Marvel Universe.[3]

The comic book arm of the company started in 1939 as Timely Publications, and by the 1950s was generally known as Atlas Comics. Marvel's modern incarnation dates from 1961, with the launching of Fantastic Four and other superhero titles created by Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and others. Marvel has since become the largest American comic book publisher over long time competitor DC Comics.[4]

Contents |

[edit] History

[edit] Timely Publications

Martin Goodman founded the company later known as 'Marvel Comics' under the name "Timely Publications" in 1939.[5] Goodman, a pulp-magazine publisher whose first publication was a Western pulp in 1933, expanded into the emerging — and by then already highly popular — new medium of comic books. Goodman began his new line from his existing company's offices at 330 West 42nd Street, New York City, New York. He officially held the titles of editor, managing editor, and business manager, with Abraham Goodman officially listed as publisher.[5]

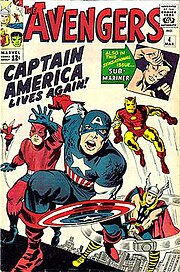

Timely's first publication, Marvel Comics #1 (Oct. 1939), contained the first appearance of Carl Burgos' android superhero the Human Torch, and the first generally available appearance of Bill Everett's anti-hero Namor the Sub-Mariner, among other features. The contents of that sales blockbuster[6] were supplied by an outside packager, Funnies, Inc., but by the following year Timely had a staff in place. With the second issue the series title changed to Marvel Mystery Comics.

The company's first true editor, writer-artist Joe Simon, teamed up with soon-to-be industry legend Jack Kirby to create one of the first patriotically themed superheroes, Captain America, in Captain America Comics #1. (March 1941) It, too, proved a major sales hit, with a circulation of nearly one million.[6]

While no other Timely character would achieve the success of these "big three", some notable heroes — many continuing to appear in modern-day retcon appearances and flashbacks — include the Whizzer, Miss America, the Destroyer, the original Vision, and the Angel. Timely also published one of humor cartoonist Basil Wolverton's best-known features, "Powerhouse Pepper,"[7][8] as well as a line of children's funny animal comics whose most popular characters were Super Rabbit and the duo Ziggy Pig and Silly Seal.

Goodman hired a teen-aged relative,once said Stanley Lieber, as a general office assistant in 1939. When editor Simon left the company in late 1941, Goodman made Lieber — by then writing pseudonymously as "Stan Lee" — interim editor of the comics line, a position Lee kept for decades except for three years during his World War II military service. Lee wrote extensively for Timely, contributing to a number of different titles.

[edit] Atlas Comics

Post-war American comics saw superheroes falling out of fashion. Goodman's comic-book line dropped superheroes and expanded into a wider variety of genres than even Timely had published, emphasizing horror, Westerns, humor, funny-animal, men's adventure-drama, crime, and war comics, later adding a helping of jungle books, romance titles, and even espionage, medieval adventure, Bible stories and sports. Like other publishers, Atlas also courted female readers with mostly humorous comics about models and career women.

Goodman began using the globe logo of Atlas, the newsstand-distribution company he owned, on comics cover-dated November 1951. This united a line put out by the same publisher, staff, and freelancers through 59 shell companies, from Animirth Comics to Zenith Publications.

Atlas, rather than innovate, took what it saw as the proven route of following popular trends in TV and movies — Westerns and war dramas prevailing for a time, drive-in movie monsters another time — and even other comic books, particularly the EC horror line.[9] Atlas also published a plethora of children's and teen humor titles, including Dan DeCarlo's Homer, the Happy Ghost (a la Casper the Friendly Ghost) and Homer Hooper (a la Archie Andrews). Atlas unsuccessfully attempted to revive superheroes in Young Men #24-28 (Dec. 1953 - June 1954), with the Human Torch (art by Syd Shores and Dick Ayers, variously), the Sub-Mariner (drawn and most stories written by Bill Everett), and Captain America (writer Stan Lee, artist John Romita Sr.).

[edit] 1960s

The first comic book under the Marvel Comics brand, the science-fiction anthology Amazing Adventures #3, showed the "MC" box on its cover. Cover-dated August 1961, it was published May 9, 1961.[10] Then, in the wake of DC Comics' success in reviving superheroes in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly with the Flash, Green Lantern, and other members of the team the Justice League of America, Marvel followed suit.[11] The introduction of modern Marvel's first superhero team, in The Fantastic Four #1, cover-dated November 1961, began establishing the company as known as of 2009[update].

Editor-writer Stan Lee and freelance artist Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four, reminiscent of the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown that Kirby had created for DC in 1957, originated in a Cold War culture that led their creators to deconstruct the superhero conventions of previous eras and better reflect the psychological spirit of their age.[12] Eschewing such comic-book tropes as secret identities and even costumes at first, having a monster as one of the heroes, and having its characters bicker and complain in what was later called a "superheroes in the real world" approach, the series represented a change that proved to be a great success.[13] Marvel began publishing further superhero titles featuring such heroes and antiheroes as the Hulk, Spider-Man, Thor, Ant-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men and Daredevil, and such memorable antagonists as Doctor Doom, Magneto, Galactus, the Green Goblin, and Doctor Octopus. The most successful new series was The Amazing Spider-Man, by Lee and Steve Ditko. Marvel even lampooned itself and other comics companies in a parody comic, Not Brand Echh (a play on Marvel's dubbing of other companies as "Brand Echh", a la the then-common phrase "Brand X").[14]

Marvel's comics had a reputation for focusing on characterization to a greater extent than most superhero comics before them.{[fact}} This was true of The Amazing Spider-Man in particular. Its young hero suffered from self-doubt and mundane problems like any other teenager. Marvel superheroes are often flawed, freaks, and misfits, unlike the perfect, handsome, athletic heroes found in previous traditional comic books. Some Marvel heroes looked like villains and monsters. In time, this non-traditional approach would revolutionize comic books.

Comics historian Peter Sanderson wrote that in the 1960s,

| “ | DC was the equivalent of the big Hollywood studios: After the brilliance of DC's reinvention of the superhero ... in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it had run into a creative drought by the decade's end. There was a new audience for comics now, and it wasn't just the little kids that traditionally had read the books. The Marvel of the 1960s was in its own way the counterpart of the French New Wave.... Marvel was pioneering new methods of comics storytelling and characterization, addressing more serious themes, and in the process keeping and attracting readers in their teens and beyond. Moreover, among this new generation of readers were people who wanted to write or draw comics themselves, within the new style that Marvel had pioneered, and push the creative envelope still further.[15] | ” |

Lee became one of the best-known names in comics, with his charming personality and relentless salesmanship of the company. His sense of humor and generally lighthearted manner became the "voice" that permeated the stories, the letters and news pages, and the hyperbolic house ads of that era's Marvel Comics. He fostered a clubby fan-following with Lee's exaggerated depiction of the Bullpen (Lee's name for the staff) as one big, happy family. This included printed kudos to the artists, who eventually co-plotted the stories based on the busy Lee's rough synopses or even simple spoken concepts, in what became known as the Marvel Method, and contributed greatly to Marvel's product and success. Kirby in particular is generally credited for many of the cosmic ideas and characters of Fantastic Four and The Mighty Thor, such as the Watcher, the Silver Surfer and Ego the Living Planet, while Steve Ditko is recognized as the driving artistic force behind the moody atmosphere and street-level naturalism of Spider-Man and the surreal atmosphere of Dr. Strange. Lee, however, continues to receive credit for his well-honed skills at dialogue and sense of storytelling, for his keen hand at choosing and motivating artists and assembling creative teams, and for his uncanny ability to connect with the readers — not least through the nickname endearments he bestowed in the credits and the monthly "Bullpen Bulletins" and letters pages, giving readers humanizing hype about the likes of "Jolly Jack Kirby," "Jaunty Jim Steranko," "Rascally Roy Thomas," "Jazzy Johnny Romita," and others, right down to letterers "Swingin' Sammy Rosen" and "Adorable Artie Simek."

Lesser-known staffers during the company's industry-changing growth[citation needed] in the 1960s (some of whom worked primarily for Marvel publisher Martin Goodman's umbrella magazine corporation) included circulation manager Johnny Hayes, subscriptions person Nancy Murphy, bookkeeper Doris Siegler, merchandising person Chip Goodman (son of publisher Martin), and Arthur Jeffrey, described in the December 1966 "Bullpen Bulletin" as "keeper of our MMMS [Merry Marvel Marching Society] files, guardian of our club coupons and defender of the faith".

In the fall of 1968, company founder Goodman sold Marvel Comics and his other publishing businesses to the Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation'. It grouped these businesses in a subsidiary called Magazine Management Co.' Goodman remained as publisher.[16]

[edit] 1970s

In 1971, the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare approached Marvel Comics editor-in-chief Stan Lee to do a comic-book story about drug abuse. Lee agreed and wrote a three-part Spider-Man story portraying drug use as dangerous and unglamorous. However, the industry's self-censorship board, the Comics Code Authority, refused to approve the story because of the presence of narcotics, deeming the context of the story irrelevant. Lee, with Goodman's approval, published the story regardless in The Amazing Spider-Man #96-98 (May-July 1971), without the Comics Code seal. The storyline was well-received and the Code was subsequently revised the same year.[17]

Goodman retired as publisher in 1972 and Lee succeeded him, stepping down from running day-to-day operations at Marvel. A series of new editors-in-chief oversaw the company during another slow time for the industry. Once again, Marvel attempted to diversify, and with the updating of the Comics Code achieved moderate to strong success with titles themed to horror (The Tomb of Dracula), martial arts, (Shang-Chi: Master of Kung Fu), sword-and-sorcery (Conan the Barbarian, Red Sonja), satire (Howard the Duck) and science fiction ("Killraven" in Amazing Adventures and, late in the decade, the long running Star Wars series). Some of these were published in larger-format black and white magazines, that targeted mature readers, under its Curtis Magazines imprint. Marvel was able to capitalize on its successful superhero comics of the previous decade by acquiring a new newsstand distributor and greatly expanding its comics line. Marvel pulled ahead of rival DC Comics in 1972, during a time when the price and format of the standard newsstand comic were in flux. Goodman increase the price and size of Marvel's November 1971 cover-dated comics from 15 cents for 39 pages total to 25 cents for 52 pages. DC followed suit, but Marvel the following month dropped its comics to 20 cents for 36 pages, offering a lower-priced product with a higher distributor discount.[18]

In 1973, Perfect Film and Chemical Corporation changed its name to Cadence Industries, which in turn renamed Magazine Management Co. as Marvel Comics Group. Goodman, now completely disconnected from Marvel, set up a new company called Atlas/Seaboard Comics in 1974, reviving Marvel's old Atlas name, but this lasted only a year-and-a-half.[19]

In the mid-1970s, a decline of the newsstand distribution network affected Marvel. Cult hits such as Howard the Duck were the victims of the distribution problems, with some titles reporting low sales when in fact they were being resold at a later date in the first specialty comic-book stores.[citation needed] But by the end of the decade, Marvel's fortunes were reviving, thanks to the rise of direct market distribution — selling through those same comics-specialty stores instead of newsstands.

In October 1976, Marvel, which already licensed reprints in different countries, including the UK, created a superhero specifically for the British market. Captain Britain debuted exclusively in the UK, and later appeared in American comics.

[edit] 1980s

In 1978 Jim Shooter became Marvel's editor-in-chief. Although a controversial personality, Shooter cured many of the procedural ills at Marvel (including repeatedly missed deadlines) and oversaw a creative renaissance at the company. This renaissance included institutionalizing creator royalties, starting the Epic imprint for creator-owned material in 1982, and launching a brand-new (albeit ultimately unsuccessful) line named New Universe, to commemorate Marvel's 25th anniversary, in 1986. However, Shooter was responsible for the introduction of the company-wide crossover (Contest of Champions, Secret Wars).

In 1981 Marvel purchased the DePatie-Freleng Enterprises animation studio from famed Looney Tunes director Friz Freleng and his business partner David H. DePatie. The company was renamed Marvel Productions and it produced well-known animated TV series and movies featuring such characters as G.I. Joe, The Transformers, Jim Henson's Muppet Babies, and such TV series as Dungeons & Dragons, as well as cartoons based on Marvel characters, including Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends.

In 1986, Marvel was sold to New World Entertainment, which within three years sold it to MacAndrews and Forbes, owned by Revlon executive Ronald Perelman. Perelman took the company public on the New York Stock Exchange and oversaw a great increase in the number of titles Marvel published. As part of the process, Marvel Productions sold its back catalog to Saban Entertainment (acquired in 2001 by Disney).

[edit] 1990s

Marvel earned a great deal of money and recognition during the early decade's comic-book boom, launching the highly successful 2099 line of comics set in the future (Spider-Man 2099, etc.) and the creatively daring though commercially unsuccessful Razorline imprint of superhero comics created by novelist and filmmaker Clive Barker. Yet by the middle of the decade, the industry had slumped and Marvel filed for bankruptcy amidst investigations of Perelman's financial activities regarding the company.[citation needed]

In 1991 Marvel began selling Marvel Universe Cards with trading card maker Impel. These were collectible trading cards that featured the characters and events of the Marvel Universe.

Marvel in 1992 acquired Fleer Corporation, known primarily for its trading cards, and shortly thereafter created Marvel Studios, devoted to film and TV projects. Avi Arad became director of that division in 1993, with production accelerating in 1998 following the success of the film Blade.[citation needed]

In 1994, Marvel acquired the comic book distributor Heroes World to use as its own exclusive distributor. As the industry's other major publishers made exclusive distribution deals with other companies, the ripple effect resulted in the survival of only one other major distributor in North America, Diamond Comic Distributors Inc.[20] Creatively and commercially, the '90s were dominated by the use of gimmickry to boost sales, such as variant covers, cover enhancements, regular company-wide crossovers that threw the universe's continuity into disarray, and even special swimsuit issues. In 1996, Marvel had almost all its titles participate in the Onslaught Saga, a crossover that allowed Marvel to relaunch some of its flagship characters, such as the Avengers and the Fantastic Four, in the Heroes Reborn universe, in which Marvel defectors Jim Lee and Rob Liefeld were given permission to revamp the properties from scratch. After an initial sales bump, sales quickly declined below expected levels, and Marvel discontinued the experiment after a one-year run; the characters returned to the Marvel Universe proper. In 1998, the company launched the imprint Marvel Knights, taking place within Marvel continuity; helmed by soon-to-become editor-in-chief Joe Quesada, and featuring tough, gritty stories showcasing such characters as the Inhumans, Black Panther and Daredevil, it achieved substantial success.[citation needed]

[edit] Marvel goes public

In 1991, Perelman took Marvel public in a stock offering underwritten by Merrill Lynch and First Boston Corporation. Following the rapid rise of this immediately popular stock, Perleman issued a series of junk bonds that he used to acquire other children's entertainment companies. Many of these bond offerings were purchased by Carl Icahn Partners, which later wielded much control during Marvel's court-ordered reorganization after Marvel went bankrupt in 1996. In 1997, after protracted legal battles, control landed in the hands of Isaac Perlmutter, owner of the Marvel subsidiary Toy Biz. With his business partner Avi Arad, publisher Bill Jemas, and editor-in-chief Bob Harras, Perlmutter helped revitalize the comics line.[21]

[edit] 2000s

With the new millennium, Marvel Comics escaped from bankruptcy and again began diversifying its offerings. In 2001, Marvel withdrew from the Comics Code Authority and established its own Marvel Rating System for comics. The first title from the era to not have the code was X-Force #119 (Oct. 2001). It also created new imprints, such as MAX, a line intended for mature readers, and Marvel Age, developed for younger audiences. In addition to this is the highly successful Ultimate Marvel imprint, which allowed Marvel to reboot their major titles by deconstructing and updating its major superhero and villain characters to introduce to a new generation. This imprint exists in a universe parallel to mainstream Marvel continuity, allowing writers and artists freedom from the characters' convoluted history and the ability to redesign them, and to maintain their other ongoing series without replacing the established continuity. This also allowed Marvel to capitalize on an influx of new readers unfamiliar with comics but familiar with the characters through the film and TV franchises. The company has also revamped its graphic novel division, establishing a bigger presence in the bookstore market. As of 2007, Marvel remains a key comics publisher, even as the industry has dwindled to a fraction of its peak size decades earlier.[citation needed]

Stan Lee, no longer officially connected to the company save for the title of "Chairman Emeritus", remains a visible face in the industry. In 2002, he sued successfully for a share of income related to movies and merchandising of Marvel characters, based on a contract between Lee and Marvel from the late 1990s; according to court documents, Marvel had used "Hollywood accounting" to claim that those projects' "earnings" were not profits. Marvel Comics' parent company Marvel Entertainment continues to be traded on the New York Stock Exchange as MVL. Some of its characters have been turned into successful film franchises, the highest-grossing being the X-Men film series, starting in 2000, and the Spider-Man series, beginning in 2002[22]

In 2006, Marvel's fictional crossover event "Civil War" established federal superhero registration in the Marvel universe, creating a political and ethical schism throughout it. Also that year, Marvel created its own wiki.[23]

The company launched an online initiative late in 2007, announcing Marvel Digital Comics Unlimited, a digital archive of 2,500 back issues available for viewing, for a monthly or annual subscription fee.[24]

In 2009, Marvel Comics closed their Open Submissions Policy; therefore, they would not be accepting any art or stories from aspiring writers and artists.[25] C.B. Cebulski explained the reason was no one got hired to draw for Marvel through open subissions, and they received far too many submissions that would have never made it into the business.[25] Marvel was the last (major) company that had an Open Submissions Policy.[26]

[edit] Editors-in-chief

The Marvel editor-in-chief oversees the largest-scale creative decisions taken within the company. While the fabled Stan Lee held great authority during the decades when publisher Martin Goodman privately held his company, of which the comics division was a relatively small part, his successors have been to greater and lesser extents subject to corporate management.

The position evolved sporadically. In the earliest years, the company had a single editor overseeing the entire line. As the company grew, it became increasingly common for individual titles to be overseen separately. The concept of the "writer-editor" evolved, stemming from when Lee wrote and managed most of the line's output. Overseeing the line in the 1970s was a series of chief editors, though the titles were used intermittently. Confusing matters further, some appear to have been appointed merely by extending their existing editorial duties. By the time Jim Shooter took the post in 1978, the position of editor-in-chief was clearly defined.

In 1994, Marvel briefly abolished the position, replacing Tom DeFalco with five "group editors", though each held the title "editor-in-chief" and had some editors underneath them. It reinstated the overall editor-in-chief position in 1995, installing Bob Harras. Joe Quesada became editor-in-chief in 2000.

- Joe Simon (1940-1941)

- Stan Lee (1941-1942)

- Vincent Fago (acting editor during Lee's military service) (1942-1945)

- Stan Lee (1945-1972)

- Roy Thomas (1972-1974)

- Len Wein (1974-1975)

- Marv Wolfman (black-and-white magazines 1974-1975, entire line 1975-1976)

- Gerry Conway (1976)

- Archie Goodwin (1976-1978)

- Jim Shooter (1978-1987)

- Tom DeFalco (1987-1994)

- No overall editor-in-chief (1994-1995)

- Bob Harras (1995-2000)

- Joe Quesada (2000-present)

[edit] Offices

Located in New York City, Marvel has been successively headquartered in the McGraw-Hill Building (where it originated as Timely Comics in 1939); in suite 1401 of the Empire State Building; at 635 Madison Avenue (the actual location, though the comic books' indicia listed the parent publishing-company's address of 625 Madison Ave.); 575 Madison Avenue; 387 Park Avenue South; 10 East 40th Street; and 417 Fifth Avenue.

[edit] Marvel characters in other media

Marvel characters and stories have been adapted to many other media. Some of these adaptations were produced by Marvel Comics and its sister company, Marvel Studios, while others were produced by companies licensing Marvel material.

[edit] Television programs

Many television series, both live action and animated, have been based on Marvel Comics characters. These include multiple series for popular characters such as Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four. Of particular note were the animated series from the mid to late 90's, which were all part of the same Marvel animated universe.

Additionally, a handful of television movies based on Marvel Comics characters have been made.

[edit] Films

Marvel characters have been adapted into films including the Spider-Man, Blade and X-Men trilogies; the Fantastic Four film series, Daredevil, Elektra, Ghost Rider, Iron Man, The Incredible Hulk, Hulk, The Punisher, and Punisher: War Zone as well as the upcoming films X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Runaways, Iron Man II, Thor, The First Avenger: Captain America and The Avengers.

Additionally, a series of direct-to-DVD animated films began in 2006 with Ultimate Avengers, The Invincible Iron Man, and Doctor Strange.

[edit] Theme Parks

Marvel has licensed its characters for theme parks and attractions, including at the Universal Orlando Resort's Islands of Adventure, in Orlando, Florida, which includes rides based on the Hulk, Spider-man, and Doctor Doom, and performers costumed as Captain America, the X-Men, and Spider-Man.[27] Universal theme parks in California and Japan also have Marvel rides.[28] In early 2007 Marvel and developer the Al Ahli Group announced plans to build Marvel's first full theme park, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, by 2011.[28]

[edit] Video games

[edit] Imprints

- Icon Comics

- Marvel Adventures

- Marvel Knights

- Marvel Illustrated

- Marvel Noir

- MC2

- MAX

- Soleil

- Ultimate Marvel

- Marvel Zombies

[edit] Defunct

- Amalgam Comics

- Curtis Magazines

- Epic Comics

- Marvel 2099

- Marvel Absurd

- Marvel Age

- Malibu Comics

- Marvel Edge

- Marvel Mangaverse

- Marvel Music

- Marvel Next

- Marvel UK

- New Universe

- Paramount Comics

- Razorline

- Star Comics

- Tsunami

[edit] See also

[edit] Footnotes

- ^ "Annual Report 2007" (PDF). Marvel.com SEC Filings. http://www.marvel.com/company/pdfs/10-k_as_filed_3-25_00054158.PDF. Retrieved on 2008-05-08.

- ^ Marvel Comics: The Early Timely Years Classic Comics Suite. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ^ Ultimate Marvel Universe Retrieved October 18, 2008

- ^ Marvel Comics official site Retrieved October 18, 2008

- ^ a b Per statement of ownership, dated October 2, 1939, published in Marvel Mystery Comics #4 (Feb. 1940), p. 40; reprinted in Marvel Masterworks: Golden Age Marvel Comics Volume 1 (Marvel Comics, 2004, ISBN 0-7851-1609-5), p. 239

- ^ a b Per researcher Keif Fromm, Alter Ego #49, p. 4 (caption), Marvel Comics #1, cover-dated October 1939, quickly sold out 80,000 copies, prompting Goodman to produce a second printing, cover-dated November 1939. The latter is identical except for a black bar over the October date in the inside front cover indicia, and the November date added at the end. That sold approximately 800,000 copies. Also per Fromm, the first issue of Captain America Comics sold nearly one million copies.

- ^ Grand Comics Database: "Powerhouse Pepper"

- ^ A Smithsonian Book of Comic-Book Comics (Smithsonian Institution / Harry N. Abrams, 1981)

- ^ Per Les Daniels in Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1991) ISBN 0-8109-3821-9, pp. 67-68: "The success of EC had a definite influence on Marvel. As Stan Lee recalls, 'Martin Goodman would say, "Stan, let's do a different kind of book," and it was usually based on how the competition was doing. When we found that EC's horror books were doing well, for instance, we published a lot of horror books'."

- ^ Library of Congress copyright information at Grand Comics Database: Amazing Adventures #3

- ^ Apocryphal legend has it that in 1961, Timely and Atlas publisher Martin Goodman was playing golf with either Jack Liebowitz or Irwin Donenfeld of rival DC Comics, then known as National Periodical Publications, who bragged about DC's success with the Justice League (which had debuted in The Brave and the Bold #28 [Feb. 1960] before going on to its own title). However, film producer and comics historian Michael Uslan partly debunked the story in a letter published in Alter Ego #43 (Dec. 2004), pp. 43-44:

Goodman, a publishing trend-follower aware of the JLA's strong sales, did direct his comics editor, Stan Lee, to create a comic-book series about a team of superheroes. According to Lee in Origins of Marvel Comics (Simon and Schuster/Fireside Books, 1974), p. 16:“ Irwin said he never played golf with Goodman, so the story is untrue. I heard this story more than a couple of times while sitting in the lunchroom at DC's 909 Third Avenue and 75 Rockefeller Plaza office as Sol Harrison and [production chief] Jack Adler were schmoozing with some of us ... who worked for DC during our college summers. ... [T]he way I heard the story from Sol was that Goodman was playing with one of the heads of Independent News, not DC Comics (though DC owned Independent News). ... As the distributor of DC Comics, this man certainly knew all the sales figures and was in the best position to tell this tidbit to Goodman. ... Of course, Goodman would want to be playing golf with this fellow and be in his good graces. ... Sol worked closely with Independent News' top management over the decades and would have gotten this story straight from the horse's mouth. ” “ Martin mentioned that he had noticed one of the titles published by National Comics seemed to be selling better than most. It was a book called The [sic] Justice League of America and it was composed of a team of superheroes. ... ' If the Justice League is selling ', spoke he, ' why don't we put out a comic book that features a team of superheroes?' ” - ^ Genter, Robert. "'With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility': Cold War Culture and the Birth of Marvel Comics," The Journal of Popular Culture 40:6, 2007

- ^ Commentators such as comics historian Greg Theakston have suggested that the decision to include monsters and initially distance the new breed of superheroes from costumes was a conscious one, and born of necessity. Since DC was distributing Marvel's output at the time, Theakston theorizes that "Goodman and Lee decided to keep their superhero line looking as much like their horror line as they possibly could," downplaying "the fact that [Marvel] was now creating heroes" with the knock-on effect that they ventured "into deeper waters, where DC had never considered going". See: Ro, Ronin. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution, pp. 86-88 (Bloomsbury, 2004)

- ^ Time (Oct. 31, 1960): "The Real Brand X"

- ^ Sanderson, Peter. IGN.com (Oct. 10, 2003): Comics in Context #14: "Continuity/Discontinuity"

- ^ Daniels, Les, Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1991), p. 139. ISBN 0-8109-3821-9.

- ^ Nyberg, Amy Kiste. Seal of Approval: History of the Comics Code. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, Miss., 1998

- ^ Daniels, Marvel, pp.154-155

- ^ Atlas Archives

- ^ Rozanski, Chuck, "Diamond Ended Up With 50% of the Comics Market". MileHighComics.com (n.d.)

- ^ Comic Wars by Dan Raviv. New York: Random House, 2002.

- ^ Box Office Mojo: "Franchises: Marvel Comics"

- ^ Marvel Universe wiki

- ^ Colton, David. "Marvel Comics Shows Its Marvelous Colors in Online Archive", USA Today, Nov. 12, 2007

- ^ a b Doran, Michael (2009-04-03). "C.B. Cebulski on Marvel's Closed Open Submissions Policy". Newsarama. http://www.newsarama.com/comics/090403-cebeulski-marvel-submissions.html. Retrieved on 2009-04-05.

- ^ "Marvel Ends Open Submission Policy". Newsarama. 2009-02-07. http://www.newsarama.com/comics/020927-Marvel-Submission.html. Retrieved on 2009-04-05.

- ^ Universal's Islands of Adventures: Marvel Super Hero Island official site

- ^ a b Reuters newswire, "Marvel Theme Park to Open in Dubai by 2011", March 22, 2007

[edit] References

- Marvel Entertainment official site

- The Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe

- Marvel Guide: An Unofficial Handbook of the Marvel Universe

- All in Color for a Dime by Dick Lupoff & Don Thompson ISBN 0-87341-498-5

- The Comic Book Makers by Joe Simon with Jim Simon ISBN 1-887591-35-4

- Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee by Stan Lee and George Mair ISBN 0-684-87305-2

- Jack Kirby: The TCJ Interviews, Milo George, ed. (Fantagraphics Books, Inc., 2001). ISBN 1-56097-434-6

- Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, by Les Daniels (Harry N. Abrams, New York, 1991) ISBN 0-8109-3821-9

- Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters, and the Birth of the Comic Book by Gerard Jones (Basic Books, 2004) trade paperback ISBN 0-465-03657-0

- Comic Wars by Dan Raviv ISBN 0-7679-0830-9

- Stephen Korek- Marvel comics and the future

- Origins of Marvel Comics by Stan Lee ISBN 0-7851-0579-4

- The Steranko History of Comics, Vol. 1 by James Steranko ISBN 0-517-50188-0

- Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution by Ronin Ro (Bloomsbury, 2004) ISBN 1-58234-345-4

- A Timely Talk with Allen Bellman

- Atlas Tales

- The Marvel/Atlas Super-Hero Revival of the Mid-1950s

- Jack Kirby Collector #25: "More Than Your Average Joe"

- Clive Barker official site: Comics

- Independent Heroes from the USA: Clive Barker's Razorline

- Buzzscope (June 23, 2005): "Addicted to Comics" #10 (column) by Jim Salicrup

- Daredevil: The Man Without Fear fan site: Marv Wolfman interview

[edit] External links

- Marvel Comics

- Big Comic Book DataBase: Marvel Comics

- Marvel News

- Marvel Directory

- Ultimate Central

- The Jack Kirby Museum & Research Center

- Marvel Database (Wiki)

- Marvel channel at YouTube

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||