Thou

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

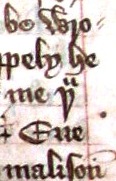

The word thou (pronounced /ðaʊ/ in most dialects) is a second person singular pronoun in English. It is now largely archaic, having been replaced in almost all contexts by you. It is still used in parts of Northern England and the far north of Scotland. Thou is the nominative form; the oblique/objective form is thee (functioning as both accusative and dative), and the possessive is thy or thine. Almost all verbs following thou have the endings -st or -est; e.g., "thou goest". In Middle English, thou was sometimes abbreviated by putting a small "u" over the letter thorn: þͧ (![]() ).

).

Originally, thou was simply the singular counterpart to the plural pronoun ye, derived from an ancient Indo-European root. Following a process found in other Indo-European languages, thou was later used to express intimacy, familiarity, or even disrespect while another pronoun, you, the oblique/objective form of ye, was used for formal circumstances (see T-V distinction). In the 17th century, thou fell into disuse in the standard language but persisted, sometimes in altered form, in regional dialects of England and Scotland,[2] as well as in the language of such religious groups as the Society of Friends. In standard modern English, thou continues to be used only in formal religious contexts, in literature that seeks to reproduce archaic language, and in certain fixed phrases such as "holier than thou" and "fare thee well". For this reason, many associate the pronoun with solemnity or formality, connotations at odds with the word's history. Many dialects have compensated for the lack of a singular/plural distinction caused by the disappearance of thou through the creation of new plural pronouns or pronominal constructions, such as y'all, all y'all, yinz, youse, you lot, and you guys. These vary regionally and are usually restricted to colloquial speech.

Contents |

[edit] Grammar

Because thou has passed out of common use, its traditional forms are often confused by those attempting to imitate older manners of speech.

[edit] Declension

The English personal pronouns have standardised declension according to the following table:

| Nominative | Objective | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Person | singular | I | me | my / mine[1] | mine |

| plural | we | us | our | ours | |

| 2nd Person | singular informal | thou | thee | thy / thine[1] | thine |

| plural or formal singular | ye | you | your | yours | |

| 3rd Person | singular | he / she / it | him / her / it | his / her / his (its)[2] | his / hers / his (its)[2] |

| plural | they | them | their | theirs | |

- a b In a deliberately archaic style, the possessive forms are used as the genitive before words beginning with a vowel sound (for example, thine eyes) similar to how an is used instead of a in an eye. This practice is followed irregularly in the King James Bible, but is more regular in earlier literature, such as the Early Modern English texts of Geoffrey Chaucer. Otherwise, "my" and "thy" is attributive (my/thy goods,) and "mine" and "thine" are predicative (they are mine/thine). Shakespeare pokes fun at this custom when the character Bottom says "mine eyen" in A Midsummer Night's Dream.

- a b From the early Early Modern English period up until the 17th century, his was the possessive of the third person neuter it as well as of the 3rd person masculine he. Later, the neologism its became common. "Its" appears only once in the 1611 King James Bible (Leviticus 25:5).

[edit] Conjugation

Verb forms used after thou generally end in -st or -est in the indicative mood in both the present and the past tenses. These forms are used for both strong and weak verbs:

Typical examples of the standard present and past tense forms follow. The e in the ending is optional; early English spelling had not yet been standardized. In verse, the choice about whether to use the e often depended upon considerations of meter.

- to know: thou knowest, thou knewest

- to drive: thou drivest, thou drovest

- to make: thou makest, thou madest

- to love: thou lovest, thou lovedest

A few verbs have irregular thou forms:

- to be: thou art (or thou beest), thou wast (or thou wert; originally thou were)

- to have: thou hast, thou hadst

- to do: thou dost /dʌst/ (or thou doest in non-auxiliary use) and thou didst

- shall: thou shalt

- will: thou wilt

In Old English, the second-person singular verb inflection was -es. This came down unchanged from Indo-European and can be seen in quite distantly related Indo-European languages: Russian знаешь, znayesh, thou knowest; Latin amas, thou lovest. (This is parallel to the history of the third-person form, in Old English -eþ, Russian, знает, znayet, he knoweth, Latin amat he loveth.) The anomalous development from -es to modern English -est, which took place separately at around the same time in the closely related German and Frisian languages, is understood to be caused by an assimilation of the consonant of the pronoun, which often followed the verb. This is most readily observed in German: liebes du > liebstu > liebst du (thou lovest). The three languages belong to the West Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages, of which Frisian is the closest to English.

[edit] Comparison

| Early Modern English | Modern West Frisian | Modern German | Modern English |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thou hast | Do hast [doː hast] |

Du hast [duː hast] |

You have /juː hæv/ |

| She hath | Sy hat [zɛi hat] |

Sie hat [ziː hat] |

She has /ʃiː hæz/ |

| What hast thou? | Wat hasto? [vat hast̬o] |

Was hast du? [vas hast duː] |

What do you have? /hwɒt duː juː hæv/ |

| What hath she? | Wat hat sy? [vat hat zɛi] |

Was hat sie? [vas hat ziː] |

What does she have? /hwɒt dʌz ʃiː hæv/ |

| Thou goest | Do giest [doː ɡiəst] |

Du gehst [duː ɡeːst] |

You go /juː ɡoʊ/ |

| Thou dost | Do dochst [doː doxst] |

Du tust [duː tuːst] |

You do /juː duː/ |

| Thou be'st (variant thou art) |

Do bist [doː bɪst] |

Du bist [duː bɪst] |

You are /juː ɑr/ |

In the subjunctive and imperative moods, the ending in -(e)st is dropped, although it is generally retained in thou wert, the second-person singular past subjunctive of the verb "to be". The subjunctive forms are used when a statement is doubtful or contrary to fact; as such, they frequently occur after "if" and the poetic "and".

- If thou be Johan, I tell it thee, right with a good advice . . .;[3]

- Be Thou my vision, O Lord of my heart . . .[4]

- I do wish thou wert a dog, that I might love thee something . . .[5]

- And thou bring Alexander and his paramour before the Emperor, I'll be Actaeon . . .[6]

- O WERT thou in the cauld blast, . . . I'd shelter thee . . .[7]

In modern regional English dialects that use thou or some variant, it often takes the third person form of the verb -s. This comes from a merging of Early Modern English second person singular ending -st and third person singular ending -s into -s.

[edit] Etymology

Thou originates from Old English þú, and ultimately from the Proto-Indo-European *tu, with the expected Germanic vowel lengthening in open syllables. Thou is therefore cognate with Icelandic and Old Norse þú, modern German, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish du, Latin, Spanish, French, Portuguese, Catalan, Italian, Irish, Lithuanian, Latvian and Romanian tu or tú, Greek σύ, (sy), Slavic ты / ty or ти / ti, Armenian դու (dow), Hindi तू (tū), Bengali: তুই (tui), Persian تُو (to), and Sanskrit त्वम् (tvam). A cognate form of this pronoun exists in almost every other Indo-European language.[8]

[edit] History

In Old English, thou was governed by a simple rule: thou addressed one person, and ye more than one. After the Norman Conquest, which marks the beginning of the French vocabulary influence that characterized the Middle English period, thou was gradually replaced by the plural ye as the form of address for a superior person and later for an equal. For a long time, however, thou remained the most common form for addressing an inferior person.

The practice of matching singular and plural forms with informal and formal connotations is called the T-V distinction, and in English is largely due to the influence of French. This began with the practice of addressing kings and other aristocrats in the plural. Eventually, this was generalized, as in French, to address any social superior or stranger with a plural pronoun, which was felt to be more polite. In French, tu was eventually considered either intimate or condescending (and, to a stranger, potentially insulting), while the plural form vous was reserved and formal.

In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson, in A Grammar of the English Tongue, wrote: "...in the language of ceremony... the second person plural is used for the second person singular...", implying that the second person singular was still in everyday use. By contrast, The Merriam Webster Dictionary of English Usage says that for most speakers of southern British English, thou had fallen out of everyday use, even in familiar speech, by sometime around 1650.[9] Thou persisted in a number of religious, literary, and regional contexts, and those pockets of continued use of the pronoun tended to undermine the T-V distinction.

One notable consequence of the decline in use of the second person singular pronouns thou, thy, and thee is the obfuscation of certain sociocultural elements of Early Modern English texts, such as many character interactions in Shakespeare's plays. In Richard III, for instance, the conversation between the Duke of Clarence and the two murderers takes on a very different tone if it is read in light of the social connotations of the pronouns used by the characters.[10]

[edit] Use as a verb

Many Indo-European languages contain verbs meaning "to address with the informal pronoun", such as Dutch jouen, German duzen, French tutoyer, Spanish tutear, Russian тыкать (tykat'), Polish tykać, etc. Although uncommon in English, the usage did appear, such as at the trial of Sir Walter Raleigh in 1603, when Sir Edward Coke, prosecuting for the Crown, reportedly sought to insult Raleigh by saying,

- I thou thee, thou traitor![11]

here using thou as a verb meaning "to call thou". Although the practice never took root in Standard English, it occurs in dialectal speech in the north of England. A formerly common refrain in Yorkshire, which admonished overly familiar children, declared:

- Don't thee tha them as thas thee!

And similar in Lancashire dialect:

- Don't thee me, thee; I's you to thee!

[edit] Religious uses

As William Tyndale translated the Bible into English in the early 1500s, he sought to preserve the singular and plural distinctions that he found in his Hebrew and Greek originals. Therefore, he consistently used thou for the singular and ye for the plural regardless of the relative status of the speaker and the addressee. By doing so, he probably saved thou from utter obscurity and gave it an air of solemnity that sharply distinguished it from its French counterpart. Tyndale's usage was imitated in the King James Bible, and remained familiar because of that translation.[12]

The 1662 Book of Common Prayer, which is still an authorized form of worship in the Church of England, retains the 17th-century language and uses the word thou to refer to the singular second person. It is treasured among worshippers because of the beauty of its language, and is considered one of the greatest works in English.[13]

Quakers formerly used thee as an ordinary pronoun; the stereotype has them saying thee for both nominative and accusative cases.[14] This was started by George Fox at the beginning of the Quaker movement as an attempt to preserve the egalitarian familiarity associated with the pronoun, who called it "plain speaking". Most Quakers have abandoned this usage. At its beginning, the Quaker movement was particularly strong in the northwestern areas of England, and particularly in the north Midlands area. The preservation of thee in Quaker speech may relate to this history.[15] Modern Quakers who choose to use this manner of "plain speaking" often use the "thee" form without any corresponding change in verb form, for example, is thee or were thee.[16]

In Latter-Day Saint prayer tradition, the terms "thee" and "thou" are always and exclusively used to address God, as a mark of respect. [17]

In the English translations of the scripture of the Bahá'í Faith, the terms thou and thee are also used. Shoghi Effendi, the Guardian of the the Bahá'í Faith, adopted a style that was somewhat removed from everyday discourse when translating the texts from their original Arabic or Persian to capture some of the poetic and metaphorical nature of the text in the original languages and to convey the idea that the text was to be considered holy.[18]

The Revised Standard Version of the Bible, which first appeared in 1946, retained the pronoun thou exclusively to address God, using you in other places. This was done to preserve the tone, at once intimate and reverent, that would be familiar to those who knew the King James Version and read the Psalms and similar text in devotional use.[19] The New American Standard Bible (1971) made the same decision, but the revision of 1995 (New American Standard Bible, Updated edition) reversed it. The New Revised Standard Version (1989) omits thou entirely, and claims that it is incongruous and contrary to the original intent of the use of thou in Bible translation to adopt a distinctive pronoun to address the Deity.[20] When referring to God, "thou" is often capitalized for clarity and reverence. While Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic (the languages of the Bible) do not have a special orthography (such as capitalization) for indicating that the Deity is being referred to, their grammars are more successful than English in making noun/pronoun agreement unambiguous.

More recently, the philosopher Martin Buber has been translated into English as using the words I and Thou to describe our ideal familiar relationship with the Deity. Most languages which maintain both a formal and familiar second person pronoun address God with the familiar pronoun (the Dutch language is an exception here), since its usage derives from older times when the distinction between the pronouns was in number only, not in degree of familiarity. Because in current English usage thou is perceived, however wrongly, as more reserved and formal than you, the translation does not convey the intended meaning well—a closer, colloquial translation of the idea would be Us or You and me, or in Australian English, "Mates".

[edit] Literary uses

[edit] Shakespeare

William Shakespeare occasionally seems to use thou in the intimate, French style sense, but he is by no means consistent in using the word that way, and friends and lovers sometimes call each other ye or you as often as they call each other thou.[21][22][23] In Henry IV, Shakespeare has Falstaff mix up the two forms speaking to Prince Henry, the heir apparent and Falstaff's commanding officer, in the same lines of dialog:

- PRINCE: Thou art so fat-witted with drinking of old sack, and unbuttoning thee after supper, and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldest truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? …

- FALSTAFF: Indeed, you come near me now, Hal … And, I prithee, sweet wag, when thou art a king, as God save thy Grace – Majesty, I should say; for grace thou wilt have none –

[edit] More recent uses

Except where everyday use survives in some regions of England, the air of informal familiarity once suggested by the use of thou has disappeared; it is used in solemn ritual occasions, in readings from the King James Bible, in Shakespeare, and in formal literary compositions that intentionally seek to echo these older styles. Since becoming obsolete in most dialects of spoken English, it has nevertheless been used by more recent writers to address exalted beings such as God,[24] a skylark,[25] Achilles,[26] and even The Mighty Thor.[27] In Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader addresses the Emperor with the words: "What is thy bidding, my master?" In Leonard Cohen's song Bird on a Wire, he promises his beloved that he'll reform, saying "I will make it all up to thee." And in Diana Ross's song 'Upside Down' we hear the lyric "Respectfully I say to thee I'm aware that you're cheatin'." These recent uses of the pronoun suggest something far removed from intimate familiarity or condescension, while they could be seen as mirroring the mode of address used with the Deity in the Bible as discussed above.

Most modern writers have no experience using thou in daily speech; they are therefore vulnerable to confusion of the traditional verb forms. The most common mistake in artificially archaic modern writing is the use of the old third person singular ending -eth with thou, for example thou thinketh. The converse—the use of the second person singular ending -est for the third person—also occurs ("So sayest Thor!"—spoken by Thor). This usage often shows up in modern parody and pastiche[28] in an attempt to make speech appear either archaic or formal. The latter is ironic as thou was historically informal, you being the formal form. The forms thou and thee are often transposed (as in Wallace Stegner's Angle of Repose).

In the fictional teenage ideolect nadsat, invented for Anthony Burgess' novel A Clockwork Orange (and the film adaptation), Alex and his droogs regularly use "thou", which fits in with their semi-Edwardian clothing. For example, when fighting a rival gang, Alex addresses them thus (note the mixing of "you" and "thou" for the second person):

- Well, well, well! Well if it isn't fat stinking Billy goat Billy Boy in poison! [i.e., in person] How art thou, thou globby bottle of cheap stinking chip oil? Come and get one in the yarbles, if you have any yarbles, you eunuch jelly thou![citation needed]

Some translators render the T-V distinction in English with "thou" and "you", particularly in places where you appears in the place of expected thou, or vice versa. This practice has largely fallen out of use. Ernest Hemingway, in his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, uses the forms "thou" and "you" in order to reflect the relationships between his Spanish-speaking characters.

Thou is often falsely interpreted as having been formal; its use today can give an impression of stiltedness. In reading passages with thou and thee, many modern readers stress the pronouns and the verb endings. Traditionally, however, the e in -est ought to be unstressed, and thou and thee should be no more stressed than you.

[edit] Current usage

You is now the standard English second-person pronoun and encompasses both the singular and plural senses. In some dialects, however, "thou" has persisted,[29] and in others the vacuum created by the loss of a distinction has led to the creation of new forms of the second-person plural. The forms vary across the English-speaking world and between literature and the spoken language.[30]

[edit] Persistence of second-person singular

In traditional dialects, thou is used in the counties of Westmorland, Durham, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Staffordshire, Derbyshire and some western parts of Nottinghamshire.[31]Such dialects normally also preserve distinct verb forms for the singular second person, for example thee coost (standard English: you could, archaic: thou couldst) in northern Staffordshire. Throughout rural Yorkshire, the old distinction between nominative and objective is preserved.[citation needed] The possessive is often written as thy in local dialect writings, but is pronounced as an unstressed tha, and the possessive form of tha has in modern usage almost exclusively followed other English dialects in becoming yours or the local[specify] word your'n (from your one):

| Nominative | Objective | Genitive | Possessive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Person | singular | tha | thee | thy (tha) | yours / your'n |

The apparent incongruity between the archaic nominative, objective and genitive forms of this pronoun on the one hand and the modern possessive form on the other may be a signal that the linguistic drift of Yorkshire dialect is causing tha to fall into disuse; however, a measure of local pride in the dialect may be counteracting this.

Some other variants are specific to certain areas. In Sheffield, the pronunciation of the word was somewhere in between a /d/ and a /th/ sound, with the tongue at the bottom of the mouth; this led to the nickname of the "dee-dahs" for people from Sheffield. In Lancashire and West Yorkshire, ta was used as an unstressed shortening of thou, which can be found in the song "On Ilkla Moor Baht 'at". These variants are no longer in use.

The use of the word "thee" in the hit song "I Predict a Riot" by Leeds band Kaiser Chiefs ("Watching the people get lairy / is not very pretty, I tell thee") caused some comment[32] by people who were unaware that the word is still in use in the Yorkshire dialect.

The use persists somewhat in the West Country dialects, albeit somewhat affected. Some of the Wurzels songs include "Drink Up Thy Cider" and "Sniff Up Thy Snuff".[33]

Thoo has also been used in the Orcadian Scots dialect in place of the singular informal thou. In Shetlandic, the other form of Insular Scots, du is used.

[edit] Loss of second person plural

English once drew a clear distinction between the singular and plural forms of the second person pronoun. As discussed above, thou and thee were the subjective and objective forms of the singular second person. With some important exceptions, thou is no longer used in the modern language. Ye and you were the plural subjective and objective forms of the second person pronoun. Perhaps even more than thou, ye is almost completely dead as a linguistic expression. It survives in archaisms such as "what say ye" and "hear ye," and in deliberate efforts at irony, such as in the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail, in which the knights are warned by an enchanter:

| “ | Follow! But! follow only if ye be men of valour, for the entrance to this cave is guarded by a creature so foul, so cruel that no man yet has fought with it and lived! Bones of full fifty men lie strewn about its lair. So, brave knights, if you do doubt your courage or your strength, come no further, for death awaits you all with nasty big pointy teeth. | ” |

These lines present an interesting mixture of old and new styles. To establish the antiquity of the scene, the actor (John Cleese) uses the ancient form ("if ye be men of valour"), then, having accomplished this with one ye, he switches back to the modern forms, saying "if you do doubt your courage" and "death awaits you all"). The lack of a modern distinction between singular and plural you created a need for you all to make it clear that the actor is addressing the entire company of knights. Note that in the last sentence, the first you is nominative, while you (all) is objective and ye would actually be incorrect.

[edit] See also

[edit] Notes

- ^ "thou, thee, thine, thy (prons.)", Kenneth G. Wilson, The Columbia Guide to Standard American English. 1993. Online at Bartleby.com, retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ^ Shorrocks, 433–438.

- ^ Middle English carol: If thou be Johan, I tell it the

Ryght with a good aduyce

Thou may be glad Johan to be

It is a name of pryce. - ^ Eleanor Hull, Be Thou My Vision, 1912 translation of traditional Irish hymn, Rob tu mo bhoile, a Comdi cride.

- ^ Shakespeare, Timon of Athens, act IV, scene 3.

- ^ Christopher Marlowe, Dr. Faustus, act IV, scene 2.

- ^ Robert Burns, O Wert Thou in the Cauld Blast(song), lines 1–4.

- ^ Entries for thou and *tu, in The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

- ^ Entry for thou in Merriam Webster's Dictionary of English Usage.

- ^ Shakespeare, William. "The Tragedy of King Richard The Third". Act 1 Scene 4, including the murder of Clarence. Richard III Society, American Branch, Online Library of Primary Texts and Secondary Sources. Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ^ Reported, among many other places, in H. L. Mencken, The American Language (1921), ch. 9, ss. 4., "The pronoun".

- ^ David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography. (Yale, 1995) ISBN 0-300-06880-8. See also David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. (Yale, 2003) ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- ^ The Book of Common Prayer. The Church of England. Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

- ^ See, for example, The Quaker Widow by Bayard Taylor

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (Oxford, 1991). ISBN 0-19-506905-6

- ^ Ezra Kempton Maxfield, "Quaker "Thee" and Its History," American Speech, vol. 1, No. 12 (Sept. 1926), pp. 638-644.

- ^ Dallin H. Oaks, "The Language of Prayer," Ensign, May 1983.

- ^ Malouf, Diana (1984-11), "The Vision of Shoghi Effendi", Proceedings of the Association for Baha'i Studies, Ninth Annual Conference, Ottawa, Canada, pp. 129–139

- ^ Preface to the Revised Standard Version 1971

- ^ NRSV: To the Reader

- ^ Cook, Hardy M., et al. (1993). "You/Thou in Shakespeare's Work". SHAKSPER: The Global, Electronic Shakespeare Conference. http://www.shaksper.net/archives/1993/0938.html.

- ^ Calvo, Clara (1992). "'Too wise to woo peaceably': The Meanings of Thou in Shakespeare's Wooing-Scenes". Maria Luisa Danobeitia Actas del III Congreso internacional de la Sociedad espanola de estudios renacentistas ingleses (SEDERI)/Proceedings of the III International Conference of the Spanish Society for English Renaissance studies: 49-59, Granada: SEDERI.

- ^ Gabriella, Mazzon (1992). "Shakespearean 'thou' and 'you' Revisited, or Socio-Affective Networks on Stage". Carmela Nocera Avila et al. Early Modern English: Trends, Forms, and Texts: 121-36, Fasano: Schena.

- ^ Psalm 90 at the Internet Archive from the Revised Standard Version

- ^ Ode to a Skylark by Percy Bysshe Shelley

- ^ The Iliad, translated by E. H. Blakeney, 1921

- ^ The Mighty Thor at the Internet Archive 528

- ^ See, for example, Rob Liefeld, "Awaken the Thunder" (Marvel Comics, Avengers, vol. 2, issue 1, cover date Nov. 1996, part of the Heroes Reborn storyline.)

- ^ Evans, William (November 1969). "'You' and 'Thou' in Northern England". South Atlantic Bulletin 34 (4): 17–21. doi:.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. (June 1973). From Elfland to Poughkeepsie. Pendragon Press. ISBN 091401000X.

- ^ Peter Trudgill, The Dialects of England, p.93

- ^ BBC Top of the Pops web page

- ^ Wurzelmania. somersetmade ltd. Retrieved on 2007-09-12.

[edit] References

- Baugh, Albert C., and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language, 5th ed. ISBN 0-13-015166-1

- Burrow, J. A., Turville-Petre, Thorlac. A Book of Middle English. ISBN 0-631-19353-7

- Daniel, David. The Bible in English: Its History and Influence. ISBN 0-300-09930-4.

- Shorrocks, Graham. "Case Assignment in Simple and Coordinate Constructions in Present-Day English." American Speech, vol. 67, No. 4 (Winter, 1992).

- Smith, Jeremy. A Historical Study of English: Form, Function, and Change. ISBN 0-415-13272-X

- "Thou, pers. pron., 2nd sing." Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (1989). [1].

- Trudgill, Peter. (1999) Blackwell Publishing. Dialects of England. ISBN 0-631-21815-7

[edit] Bibliography

- Personal Pronouns in Present-Day English by Katie Wales (Author) ISBN 0-521-47102-8

[edit] External links

- A Grammar of the English Tongue by Samuel Johnson - includes description of 18th century use of thou

- Contemporary use of thou in Yorkshire

- Thou: The Maven's Word of the Day

- You/Thou in Shakespeare's Work (archived forum discussion)

- A Note on Shakespeare's Grammar by Seamus Cooney

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||